Anuj Kumar was puffing on his cigarette outside a tea shop in Sitamarhi’s Coaching Mandi, a hub of tuition centres that draws students from nearby villages to this small town in North Bihar. The 28-year-old was not there to study, though. He spent the day running around the district court to get his paperwork in order so that he could apply for a sub-inspector position in Bihar police.

Kumar works as a salesman for a chemical manufacturer in Janakpur, Nepal. He had come home to his village of Chhotki Bhitha for Chhath Puja, Bihar’s biggest festival. However, the desire for a government job was keeping him busy even during his holidays.

The application process frustrated Kumar, reminding him of the so-called Gen-Z revolution in Nepal, which he witnessed up close. “There is no difference between the situation of the youth in Nepal and Bihar,” he argued. “Young people there were tired of corruption. It is the same here.”

Change was needed in Bihar, too, Kumar added.

Does that mean he and others like him will vote out the ruling government in Patna when the state goes to polls next month? Kumar was doubtful. In fact, he does not plan to stay around till November 11, the polling day in his constituency. “There is nothing to be gained from voting,” he said curtly.

Kumar is not alone. In the northern parts of the state with India’s youngest population, Scroll met several young voters who are restless for a change in government, even more so after the revolution in neighbouring Nepal. But most of them don’t expect much to change in Bihar after the election. For this, they blamed caste, which, they said, trumps all other considerations in the minds of Biharis.

‘Nothing changes’

In Anuj Kumar’s village, which is a few hundred metres away from the border, his friends gathered to talk politics on Thursday morning. Most members of this group work in other parts of the country. According to them, the lack of jobs and migration were Bihar’s biggest problems. The state needed change, they said, but there were no viable options available to them.

“Unlike Nepal, we can’t just change leaders,” explained one 29-year-old who works in the army and requested not to be named. “I am a Bharatiya Janata Party supporter but I will have to vote for Janata Dal (United) because of their alliance. I like Nitish, but his time is up. He should make way for someone younger.”

He was referring to Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, who has led the state government with the support of changing alliance partners for virtually all of the last 20 years.

Despite tiring of the chief minister, the soldier said he would not vote for the Rashtriya Janata Dal, the principal Opposition party in Bihar, because, in his view, it was a party of Muslims and Yadavs only. For young supporters of the RJD, on the other hand, Nepal is a source of inspiration ahead of the vote.

“Why should it not inspire us when it is so close to us?” asked Uday Kumar Yadav, 22, an undergraduate student of Chemistry from Bindhi, another border village. “People were upset so the whole government changed there. But here, no matter what happens, nothing changes.”

Yadav said he would stop believing in democracy if Nitish Kumar were to take oath as chief minister again after the election. “If things don’t change this time, there will be a Nepal-like situation here,” he added. “The youth is very angry. For how long must we suffer?”

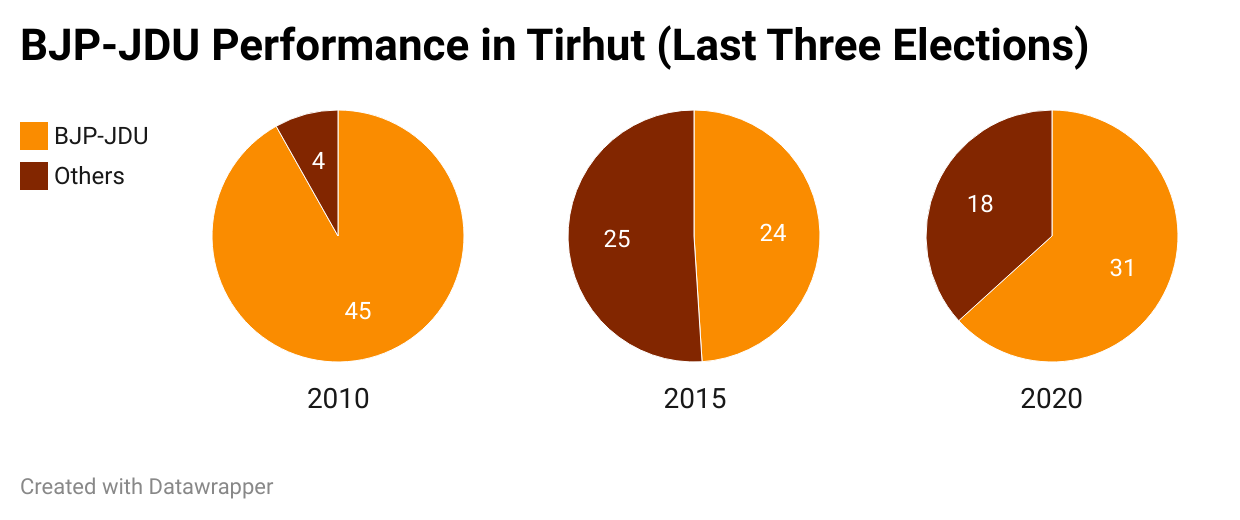

Sitamarhi district is part of the administrative division of Tirhut in North West Bihar, which sends 49 MLAs to the state assembly. The ruling coalition in Patna has dominated the politics of the region of late, especially in districts located along the Nepal border. In the 2020 election, for example, the BJP-JDU combine swept six out of Sitamarhi’s eight assembly constituencies in what was otherwise a close contest across the state.

This time, however, there is palpable anger against the candidates fielded by the two parties here, particularly among younger voters. In Chhotki Bhitha village, which is part of the Sursand assembly constituency, Anuj Kumar and his friends voiced their displeasure with the JD(U) candidate.

“I saw him for the first time when he came to our village this Diwali,” said the soldier who supports the BJP. “The JDU candidate who won from here last time never visited once in five years. Have you heard of Sunil Kumar Pintu [former MP and BJP candidate from Sitamarhi assembly constituency this time]? People want to beat him up.”

Young voters in Parihar assembly constituency also echoed this sentiment. The BJP has been winning here consistently since 2010. Scroll visited the Kushwaha-majority Bara Tola of Sutihari village in Parihar. Kushwahas are categorised as an other backward class in Bihar. Villagers criticised the implementation of the schemes that the Nitish Kumar government rolled out in the run-up to the election.

While women complained that they had not yet received the Rs 10,000 promised to them under the Mahila Rojgar Yojana, men objected to being left out of the scheme’s ambit. “We need protests like those in Nepal to fix our politicians,” said Kamlesh Kumar, 28, who runs a pan shop in the village.

Caste-first politics

It is, however, unclear if this resentment will hurt the BJP-JDU politically. Part of the reason for this is that the Opposition has not played its card very well, locals say. In Parihar, for instance, the RJD has given the ticket to Smita Gupta Purve, prompting Ritu Jaiswal, who contested this seat for the party in 2020, to file her papers as an independent candidate. Voters told Scroll that Jaiswal remains popular and will likely split the Opposition vote.

But the main reason why even those who want change don’t expect it is caste. Several young voters said that it is caste considerations that stop youth in Bihar from coming together on issues that affect them.

“The Gen Z in Bihar is asleep,” said 21-year-old Deepak Kumar, who runs an education consultancy business in Sitamarhi. “Caste determines how everybody votes here. Yadavs will only vote for Yadavs. Bhumihars pick their own leaders. There is no unity in Bihar.”

Opposition supporters, such as Uday Kumar Yadav, blame upper-caste youth for not making common cause with them. “They don’t recognise the good things the RJD has done,” he complained. “They think we support the party only because we are Yadavs.”

Others argue that the young in Bihar simply do not have the time and inclination for politics. Manish Kumar, 28, works as a wedding planner in Nepal’s Janakpur. Back in his village in Sursand assembly constituency for Chhath, he was busy flattening some land near the temple pond for the use of worshippers.

“In Bihar, there is no youth like Nepal,” he said. “There are only the unemployed. People have to struggle so much to make a living here that they can’t find time for anything else.”

College-mates Hasan Ansari and Bharosh Yadav from the nearby Chakni village matched this description. Both 23-year-olds are students of pharmacy. “We don’t care about politics,” said Ansari, sipping his tea at a local shop.

“I have no hopes from the government,” added Yadav, pulling out his smartphone to show how news about elections had filled his Facebook feed, much to his annoyance. “I know that I will have to fend for myself. Politics will not help me.”

This youth disinterest alarms the dyed-in-the-wool socialists of Sitamarhi. Almost every evening, a small group of them gathers in a room in the compound of Gandhi Maidan to talk about politics and society. As students, some members of this group had participated in the 1974 movement that catapulted Lalu Prasad Yadav and Nitish Kumar into national politics.

Activist Brajesh Kumar Sharma, who heads the Rashtriya Kisan Sabha, is one such socialist. He worried that the decline of college education was fuelling youth disenchantment with politics in Bihar.

“Today, classes are not taking place in colleges and students are going to coaching centres instead,” he said. “Movements are born when young people go to colleges and universities for their studies. There they are free from family problems and have time to think.”

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting