As Bihar heads into another election season, new research suggests that the state’s voters may be making far more calculated choices than the clichés suggest – that citizens back candidates on caste lines, paying little attention to issues such as employment or development.

In some cases, they support candidates with criminal records, betting on their ability to deliver. In others, loyalty to an ethnic party fades when that party fields tainted faces. As for dynastic politicians, responsiveness to grievances of the public often comes only when the ballot box demands it.

These findings come from a research paper by Abhinav Khemka, a post doctoral fellow at the University of Barcelona’s Department of Economics published in December. Titled Dynamics of Political Criminality, Dynasties, and Governance in Indian Democracy, the study focuses primarily on Bihar. With the state gearing up for its Assembly elections on November 6 and November 11, the research takes on added significance.

Bihar’s politics has long been haunted by the ghosts of its “strongman era”, a phenomenon born in the 1970s when booth-capturing musclemen stopped working for caste elites and began seizing power for themselves. Rejecting their traditional role of enforcers, these men stepped into the ring as candidates, reshaping the electoral battlefield.

Half a century later, as Bihar heads into another high-stakes election, many of those mafia-linked families remain woven into the state’s political fabric.

The state has never quite shaken off the impression that it is gripped by “jungleraj”, the rule of the jungle, a term popularised in 1997 by an observation of a Patna High Court judge, Dharmpal Sinha, to describe the lawlessness in the Patna Municipal Corporation.

The term was quickly picked up by the opposition to highlight the law and order situation in the state under the leadership of Rashtriya Janata Dal leader Lalu Yadav. In fact, Khemka’s paper suggests that voters tend to embrace this idea: they believe that the criminal politicians are the ones who can “get things done”.

In the first week of August, Frontline published a report saying that Bihar has seen 50 murders in the previous 20 days. The state’s business community, long perceived as a steady backer of the ruling National Democratic Alliance, took to the streets in anger on July 8, a day after the daylight killing of a prominent Patna businessman. Shops downed their shutters and rallies erupted across districts.

However, the anger of citizens, interest groups and politicians against the dominant culture of crime and the rising number of criminal incidents does not translate into outrage during the election, the study suggests.

Currently, 70% of the MLAs in the Bihar assembly face criminal charges. In 200, that number was 29%. Fifty per cent of these MLAs are accused of serious charges such as murder, attempt to murder, kidnapping and crimes against women.

According to a report by the Association for Democratic Reforms, 1,201 candidates out of the 3,722 candidates who contested the Bihar elections in 2020 had criminal charges against them.

Seventy percent of the candidates fielded by Rashtriya Janata Dal and the Bharatiya Janata Party had criminal charges, followed by Congress (64%), Lok Janshakti Party (52%), Janata Dal (United) (49%) and Bahujan Samaj Party (37%).

In last year’s Bihar Assembly by-elections, three out of the four candidates fielded by Prashant Kishor’s Jansuraj – a party that claims to be the flagbearer of alternative politics – faced serious criminal charges, including extortion, kidnapping and attempted murder.

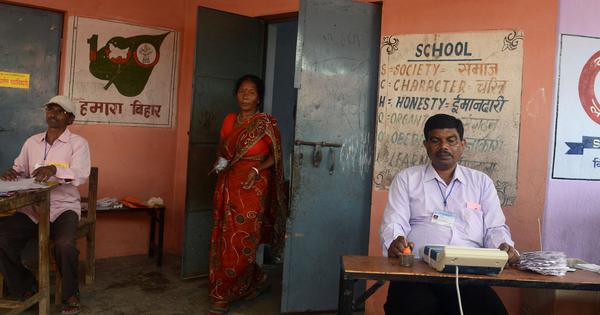

In an attempt to understand these seeming paradoxes, Khemka undertook a field study of 2,000 voters in 10 assembly constituencies of Bihar’s Sitamarhi and Muzaffarpur districts between January to April in 2022.

Simultaneously, he conducted an analysis on unskilled work allocated under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee for infrastructural development projects and their completion in the constituencies that had elected tainted politicians.

Finally, he conducted an “audit experiment” by emailing concerns arising out of public grievances to “dynast and non-dynast” legislators to check their responses.

The study zeroes in on two pivotal questions, Khemka writes. Why do voters elect criminally tainted candidates and what is the effect of electing dynastic leaders to public office?

Though only 39% of respondents reported regularly consuming news, 43% demonstrated high levels of political knowledge. Across the board, survey participants expressed strong disapproval of criminal candidates and were aware of the severity of the allegations against them.

Khemka’s research argues that “in settings where government institutions and the state have limited capacity, it allows criminal politicians to step in and take control over public goods using their delivery as a mechanism to gain voter support”.

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme is a national social security scheme that assures at least 100 days of unskilled manual work a year for every rural household. In Khemka’s evaluation of project allocation and completion, he found that in constituencies where criminal politicians had won, the rate at which projects were completed fell by 68%. But the rate of work allocation increased by 36%.

These politicians usually target welfare schemes that allocate more funds for hiring labourers than for purchasing materials. Under programmes such as MGNREGA – which mandates that at least 60% of its budget be spent on wages – this design allows them to create jobs that are highly visible to voters.

With its decentralised structure, the rural employment guarantee scheme also allows local politicians to commission projects that serve their political interests, often by exerting pressure on officials and panchayat representatives through bribes or muscle power to shape projects in the way they want.

By prioritising labour-intensive projects, politicians can channel a larger share of funds into generating more man-days of employment, helping them earn goodwill among constituents and strengthening their electoral base.

Criminal politicians try to build a “clientelistic relationship” with their voters, where voters are willing to forgive criminality if the candidate seems competent to them, Khemka writes.

He points to two forces that could be fuelling the steady rise of criminal legislators in Bihar: cash and clout. In a state where election battles are as much about resources as rhetoric, deep pockets can grease the wheels, from bribing bureaucrats to nudging local body representatives into forwarding desired projects.

Criminality, Khemka notes, is not just a liability in this landscape but a badge of competence. “Criminal politicians can use their excess wealth to not only pay political rent, but also run expensive electoral campaigns,” he writes.

He adds, “There is a large body of qualitative work in India showing that criminal politicians are viewed as effective strongmen willing to go above the law to protect individual rights and deliver resources to their constituents.”

Audit experiments in the study also paint a grim picture of Bihar’s dynastic legislators. Just 4% of all legislators responded to voter concerns emailed to them, with dynasts 6.8% less responsive than their non-dynastic counterparts. The rate fell further when the politician had a parent or spouse in politics. The only time they seemed willing to act was when there was a clear electoral payoff.

However, the study did not consider economically backward communities as a caste-category even though, with a population share of 36%, these communities form the biggest bloc in Bihar.

Despite this, the study moves beyond the notion of voters as naive or uninformed, instead portraying them as active social actors who vote with deliberation.

The state’s political economy, the author argues, is under the grip of vested interests popularly known as Bahubalis or strongmen. Their empires are built not in the halls of the legislature but in the shadows of illicit liquor networks, sand mining rackets and disputed land deals.

Over time, these strongmen have evolved into a new political class, converting the hard cash from their underground businesses into assertive forms of power: welfare schemes, service delivery and electoral dominance. As Bihar heads to the polls, will this cash-and-clout model continue to command the ballot?

Arghya Bhaskar is an independent journalist. Ritin is an interdisciplinary researcher based in Jharkhand.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting