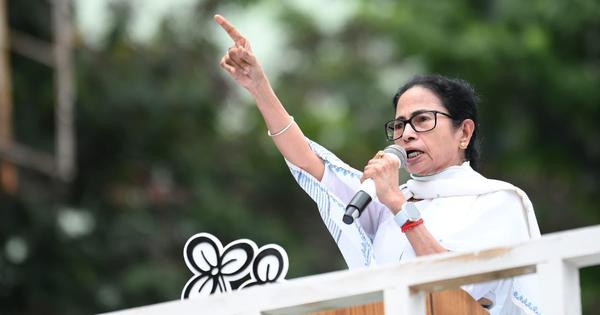

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee is locked in battle with the Election Commission over its supposed plans to draw up the state’s voter lists from scratch. She fired her latest salvo at the Commission on August 28, promising her party workers that she would not allow anybody’s name to be struck off from the voter lists.

In strictly legal terms, there is little that Banerjee can do about this. Article 324(1) of the Constitution gives the Election Commission the power to prepare the electoral rolls for national as well as state elections. In fact, the commission is currently using those powers to carry out a so-called special intensive revision of the voter rolls in Bihar.

But Bengal is not Bihar. Though legally, the commission draws up voter rolls, in practice, it needs to depend on the state government to do so. And this federal quirk gives Chief Minister Banerjee significant power to influence the process in West Bengal.

As a result, state government officials who would draw up the new voter rolls are now at the centre of a political tug of war. The chief minister and the Election Commission are engaged in a power tussle over who can command them.

Carrot and stick

At the heart of the clash between the West Bengal chief minister and the Election Commission is a simple fact: the commission depends on state governments to do its ground work.

The task of preparing voter lists before elections is typically assigned to primary school teachers and anganwadi or health care workers, who are employed by state governments. They are required to check the identities of new voters and verify the details of those who have died or permanently moved out of an area.

In the commission’s parlance, they are called booth level officers. Each booth level officer is responsible for maintaining the voter list for one polling booth, which can sometimes have as many as 1,500 registered voters.

The Commission’s data from the 2024 Lok Sabha polls shows that there were 80,530 booths in West Bengal alone. It plans to add roughly another 14,000 booths before the 2026 Assembly elections in the state.

If a Bihar-style special intensive revision were to take place in West Bengal, these booth level officers would play a crucial role in it. They would have to visit the homes of around 8 crore voters in the state to distribute forms and verify their documents. As a result, the Bengal government and the Election Commission are warring over who exactly controls the booth level officers.

While the Election Commission has yet to formally announce a special intensive revision for West Bengal, it began wooing booth level officers in July itself. Earlier, booth level officers were paid Rs 6,000 each year. The commission doubled this amount to Rs 12,000 on July 24. Two days later, it even began special intensive revision training for some booth level officers in Kolkata.

Banerjee was quick to respond. If the commission had dangled a carrot in front of booth level officers, the chief minister pulled out a stick. On July 28, she curtly reminded them that except for a few months before polls, they were answerable to the state government. Her opponents saw her comment as a thinly veiled threat to booth level officers ahead of the 2026 elections.

Jay Prakash Majumdar, who liaisons with the Election Commission on behalf of Banerjee’s party, the Trinamool Congress, blamed the commission for the controversy. He argued that before training booth level officers, the commission should have consulted all political parties and announced its programme publicly.

“They have to include all stakeholders,” Majumdar said. “They cannot do things by keeping us out. This is one task that they cannot do justice to without complete support from the state government.”

Notably, Opposition parties in Bihar had also objected to the special intensive revision on the grounds that the Election Commission did not consult them before announcing it.

While the Opposition’s complaints in Bihar had fallen on deaf ears, Majumdar warned the commission that this would hardly be the case in Bengal. “There was a National Democratic Alliance government in Bihar so they [Election Commission] silently finalised the list of booth level officers and announced the SIR,” he said. “How will they do that here? Why will our government offer support to an ill-designed scheme meant to topple it?”

Caught in the crossfire

The political wrangling over booth level officers in West Bengal has made them wary.

Some government school teachers have protested against the allotment of booth level officer duty, citing their existing workload and staff shortages in their schools. Others have voiced concerns about their safety, given the politically sensitive nature of the work that they are expected to do.

Niranjan Debnath, a 45-year-old primary school teacher in Cooch Behar district, has been a booth level officer for 11 years. But he said that what he was hearing about the special intensive revision this time was both new and unnerving.

“It is not my job to determine the citizenship of any voter’s parents or grandparents,” he said. “I will not be able to do it even if I am told to.”

Mamata Banerjee had caught on to this anxiety early on. In late June, when the Election Commission rolled out the special intensive revision in Bihar, she was among the first politicians to liken it to the National Register of Citizens. The register is meant to be a list of Indian citizens living in Assam. When the final list was published in 2019, approximately 19 lakh of 3.29 crore applicants were excluded from it.

A month later, Banerjee warned booth level officers not to “harass” people.

Her remarks triggered a political storm, drawing criticism from leaders of the Bharatiya Janata Party, her principal opponent. The state’s booth level officers, too, were following these political battles.

“The chief minister was asserting her power,” said Abdul Jaleel, a government school teacher from Murshidabad district and a newly-trained booth level officer. “Political parties will obviously create problems. We cannot do as they say. We have to collect the documents and upload them using our mobile phones. The rest is not in our hands.”

Unlike Debnath, the booth level officer from Cooch Behar, Jaleel had received special intensive revision training. He was told that he would be provided with a document checklist for verifying people’s citizenship and that Aadhaar cards will not be on the list. (This was before the Supreme Court included Aadhaar as a valid ID proof.) However, he was not given a timeline for the special intensive revision.

These statements by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee are nothing short of a blatant attempt to interfere in the democratic process and undermine the sanctity of free and fair elections.

By openly reminding Booth Level Officers (BLOs) that they are “State Government… pic.twitter.com/Dh635Bqaxs— Suvendu Adhikari (@SuvenduWB) July 28, 2025

Older issues

Jaleel, a teacher for 15 years, was assigned booth level officer duty for the first time this year. He replaced an anganwadi worker. “I was told that only permanent government employees will be made booth level officers from now,” he added.

If what Jaleel said is true, it would fulfill a longstanding demand from opposition parties in West Bengal. They oppose appointing those without permanent jobs as booth level officers, alleging that they are more susceptible to pressure from the ruling Trinamool.

While the Election Commission allows the appointment of semi-government employees as booth level officers, it advises taking “utmost care” in doing so. In October 2022, the Commission wrote to the chief electoral officers of all states, asking them to “thoroughly” verify the credentials of such workers.

“There are more than five times the required number of permanent government employees available in West Bengal,” claimed Shishir Bajoria, a Bengal BJP leader who coordinates with the Election Commission for his party. “Still, more than 40% of the chosen booth level officers here are temporary, contractual workers.”

Despite the recent changes in the appointment of booth level officers in West Bengal, Scroll found that semi-government employees continue to make the cut. In Tehatta Assembly constituency of Nadia district, for example, an anganwadi worker was replaced by another one as the booth level officer.

Even the newly appointed booth level officer, when contacted, said that she was not keen to perform the task despite the enhanced remuneration. “I don’t need the extra money,” Archana Halder explained. “I just don’t have any time to spare. I have heard that there will be a lot of work to do this time.”

Halder was hesitant to take up the added responsibility of going house-to-house, which is a key component of the special intensive revision. Her case underscores the challenges that the Commission is facing in appointing booth level officers across the state.

In some districts, the process is yet to take off. Sanjoy Roy, a government school teacher with six years of experience as a booth level officer in Malda district, said that he has not received any communication from his supervisor so far.

Asked if he would like to continue doing booth level officer duty, he added: “I don’t have the option to say no. They are struggling to find people.”

Scroll contacted the Election Commission by email to ask about the problems it is facing in appointing booth level officers for West Bengal. This piece will be updated if the commission responds.

‘Half-baked conspiracy’

Jay Prakash Majumdar of the Trinamool Congress claimed that the Election Commission was struggling to find and train booth level officers for the whole state. “The infrastructure is terribly missing on their part,” he said. “They have trained only about 800-1,000 booth level officers so far.”

Majumdar alleged that the commission could not find enough booth level officers because it was looking for those who would favour one particular party: the BJP. He called the special intensive revision a “half-baked conspiracy” and argued that the Election Commission was working in cahoots with the BJP to remove Trinamool voters from the rolls.

“They made a design which was good for Bihar,” he said. “There they had the advantage of using Nitish Kumar’s government employees. But in Bengal, the government is Mamata-di’s. It will not be that easy here.”

The BJP, however, has remained adamant on the demand for an SIR in West Bengal. Its leader Shishir Bajoria cited previous revisions to make his case.

“This would be the 14th SIR in West Bengal,” he claimed. “When the last SIR took place in 2002, names of 28 lakh voters were struck off. Mamata Banerjee [then in Opposition in Bengal] had welcomed it at that time.”

Bajoria alleged that the state’s voter lists were riddled with over 17 lakh duplicate voters. Bureaucrats had so far failed to remove them despite the BJP’s complaints because, he argued, they feared retribution from the West Bengal government.

However, he was confident that a special intensive revision would be carried out in West Bengal. To back up his belief, he pointed to the Mamata Banerjee government’s recent decision to suspend four officials whom the Election Commission had held responsible for irregularities in the voter list.

Rock and hard place

The other two major parties in West Bengal, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and Congress, find themselves in an awkward spot. Both had opposed the SIR in Bihar. In West Bengal, though, the two have long demanded a clean-up of the rolls, alleging that the ruling Trinamool uses names of dead voters on the rolls to cast bogus votes.

Sujan Chakraborty, a CPI(M) central committee member, reiterated his party’s demand for removing dead voters and double entries from the voter lists. He also welcomed the extra remuneration announced for booth level officers. But he suspected that it was done to use them in “favour” of the BJP. In the same vein, he panned the Trinamool for “threatening” booth level officers.

“Both are wrong,” Chakroborty said. “Booth level officers can understand that the pressure from New Delhi and Kolkata is the same. Why would they want to get entangled in this tussle?”

Congress spokesperson Suman Roy Chowdhury, too, expressed sympathy for booth level officers. He explained why, in his view, they could not do their work sincerely in West Bengal even if they were so inclined.

“They have to protect their jobs and their families,” he reasoned. “They will play safe to secure promotions and avoid transfers. It is very unfortunate and dangerous for democracy.”

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting