Who was the founder of the Indian National Army?

Most Indians would immediately answer that it was Subhas Chandra Bose – known by the honorific Netaji – who assembled the army to fight against the British for freedom during World War II.

As most textbooks tell it, Bose’s army was mainly staffed by Indian soldiers from the British Indian Army, who abandoned the colonial force after the Japanese entered the war in December, 1941. They hoped that the East Asian power would help them liberate the subcontinent.

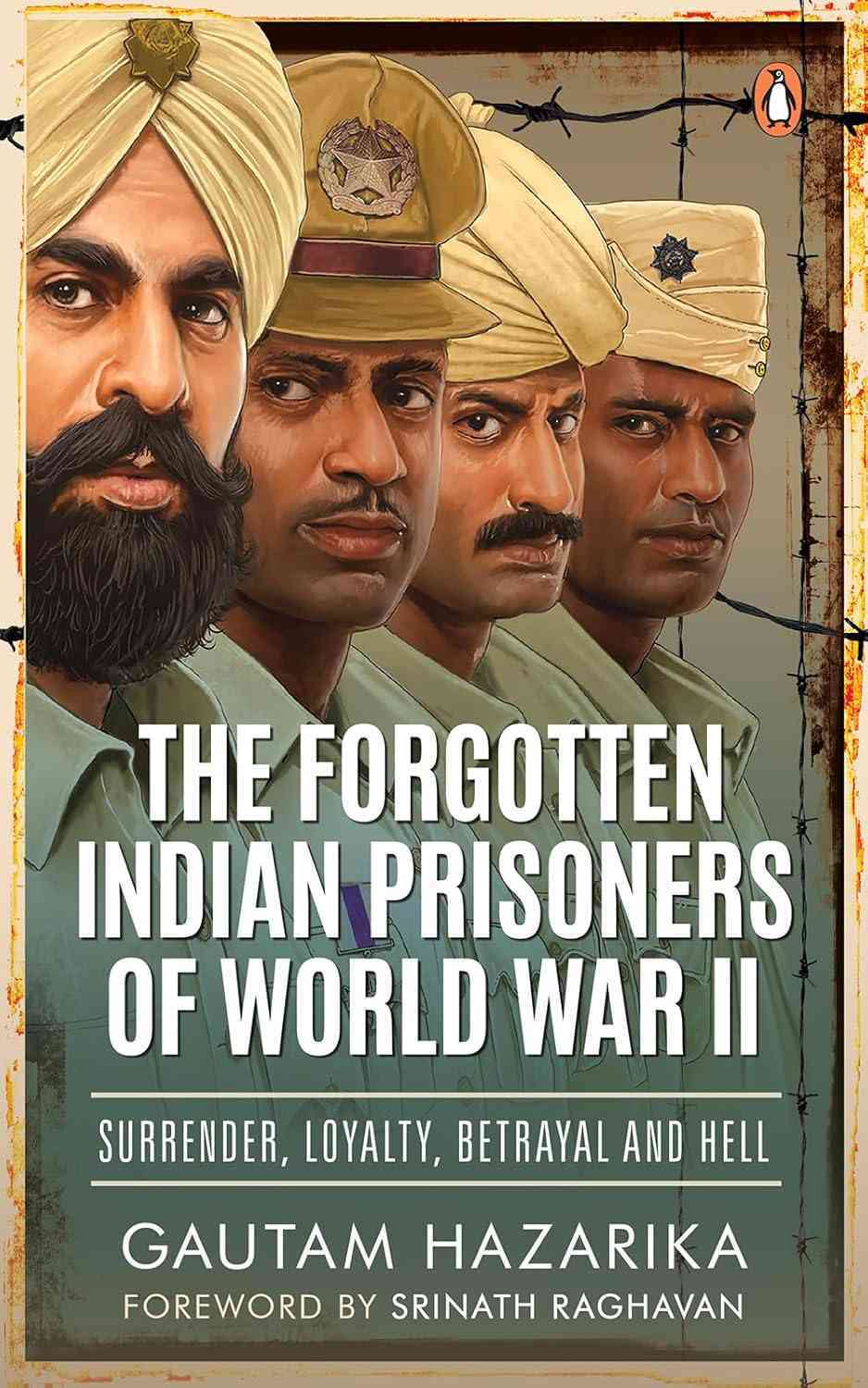

But in The Forgotten Indian Prisoners of World War II: The Untold Story of INA Soldiers, Subhas Chandra Bose, Singapore 1942, Burma Campaign, and Indian POWs Who Shaped Independence, Gautam Hazarika upturns conventional assumptions about the force.

“Contrary to popular belief, the INA was not founded by Netaji, but 18 months before he even arrived in Singapore”, in 1943, Hazarika said in an email interview. “It was fostered by a pre-war alliance between Japanese Army Intelligence and Indian nationalists outside India.”

The 55-year-old former banker who lives in Singapore began to research his book about the origins of the Indian National Army and Indian prisoners of war during the conflict three years ago, when he bought a manuscript made in the city’s Changi prison during World War II.

“What intrigued me was that it had been made by civilian internees,” Hazarika said. “I knew what a summer intern was and had read lots about army prisoners of war but not heard of internees – the manuscript opened my eyes to their world, and I started exploring other lesser-known aspects of Singapore’s World War II history. A local historian then told me that the Japanese sent Indian PoWs captured in World War II Singapore to labour in the Pacific islands, and this is how I came to this story. I was looking for a connection between India and Singapore that most did not know of, and this was it.”

Excerpts from the interview.

What was the first Indian National Army? How did it come to be formed?

World War II in Asia began with the simultaneous Japanese attack on the US Naval base in Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941, and 45 minutes before it, with the invasion of Malaya where it was already December 8.

Most of the defenders were Indian, including 32-year-old Captain Mohan Singh of the 1/14 Punjab Regiment. Ill-equipped, they were rapidly pushed back. While this happened, on December 15, Singh encountered the Japanese, who chose him to head the INA.

Unknown outside his unit, he soon became General Mohan Singh, INA and wore the mantle effectively, but also ruthlessly. He was able to recruit 90% of the men, but soon realised the Japanese were not serious about arming them to invade India, so he refused to cooperate and was arrested a year later December 29, 1942.

The Japanese respected him and knew that any ill-treatment would face a fierce backlash, so he was unharmed and exiled. All INA men had sworn a personal oath to Singh, and he had arranged for the INA to be disbanded if this happened, so it was.

How did Bose come to be projected as the central figure of the INA?

It was now that the Japanese asked Hitler to send Bose from Berlin. He arrived in Singapore in July 1943 and took the movement to greater heights. Having spent most of 1941-’42 in Hitler’s Germany, then at the height of Nazi power, Bose cultivated a similar personality cult – there was only Netaji. This continued after the war ended.

Many senior INA officers seemed embarrassed to have been under the junior, middle-class Mohan Singh, perhaps as some today disdain “chai-wallahs” who nonetheless reach great heights. Some claimed to have joined him as a last resort, when they really were enthusiastic from the start. After the war, many of those with Mohan Singh said they did not believe in him. Even if that was the case, while he was in charge, no one dared to challenge him.

Another possible reason for Mohan Singh being erased from history is that mentioning him would require stating that he was removed by the Japanese (who were in control) when he refused to cooperate with them.

This would highlight the undoubted risk Bose took in seeking the help of first Hitler, then fascist Japan, in throwing the British out of India. There would have been a price to pay. Fortunately, Germany and Japan lost the war, and this price did not get extracted.

When it came to Bose, most were enthralled by his mesmeric personality and remained loyal to him even when the INA was starving and defeated soundly by the Indian army in the few skirmishes the Japanese allowed them to be involved in. The INA sipahi was brave and endured great hardships, though hundreds deserted back to the Indian Army. Given the privations they faced, this was only human.

You have also chronicled the ordeals of the Indian prisoners of war who refused to join the INA. What happened to them?

Besides the INA story, another saga was unfolding thousands of miles away in Papua New Guinea. The Japanese shipped 17,000 Indian prisoners of war there, of whom 3,000 drowned on the way, sunk by US submarines attacking any Japanese ship even if they knew Allied prisoners of war were on board – it was accepted collateral damage.

Of the 14,000 who reached, half died in the two years there – of overwork, starvation, sickness, and many were beheaded or killed when suspected of trying to escape. This has been chronicled poignantly by Warrant Officer John Baptist Crasta of the one of the lucky ones to return home.

The skeletal survivors were liberated by Australia, and India owes them a great debt. Not only did they nurse the men back to life, but based on their evidence, also conducted 100 war crimes trials to hold the Japanese to account.

What were the biggest lessons you learned about how national histories are framed as you researched your book?

After the war ended, these men were forgotten. Our focus was on the history of the independence movement but what our soldiers did in colonial times seemed less important. This is quite common. Nations decide key narratives to focus on, not on the bravery of every individual.

But more than this, the biggest lesson is that what happened to the soldier is only half of the story. The other, and at times more important half, is what his waiting wife endured. Left alone for five years with no news of her soldier-husband, with many young children to rear on little money, it was an unimaginable ordeal.

Many were pressured to remarry but refused till they saw their husband’s dead body. How they endured, survived is a remarkable half of military history that we need to pay more attention to.

The Forgotten Indian Prisoners of World War II: The Untold Story of INA Soldiers, Subhas Chandra Bose, Singapore 1942, Burma Campaign, and Indian POWs Who Shaped Independence (Penguin India).

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting