This anthology is the result of a long engagement with literature from the Northeast. And yet, it would not have been possible without the many people who helped me, including the writers who generously responded to my call for stories. I have built warm friendships with some of the writers included in this anthology. But I always knew them first as writers. This is important, as we come from tight-knit communities where personal lives often blur the boundaries between friendship and professionalism. Their writing allowed me to see them beyond the notions of fondness and aversion that are usually in place when dealing with personal relationships.

No writing is, of course, perfect. But the writers in this anthology have shown unusual courage in putting pen to paper. For many writers from the Northeast, the terror of the blank page also means overcoming many of the stereotypes associated with the literature from the region. In this regard, these stories transgress our current understanding of literature from the Northeast, whether it be in theme, form, or style.

As anyone belonging to the region would say, the stories they grew up with reflected the political, social, and cultural upheavals of their time. A history of strife and political instability has been a key feature of the region and has made its way into the literature. There are writers, however, who are challenging this narrative and they derive inspiration from other lived realities in the region. Conflict, in their narratives, originates from the more immediate effects of social and cultural practices in everyday living. Diasporic experiences and sensibilities, too, have impacted the way writers engage with the Northeast, particularly when such identities are cause for marginalisation where belonging and transnational histories are concerned.

Literatures from the Northeast have always had transnational moorings, especially in relation to other literatures and literary traditions from Southwest China and upland Southeast Asia. Until very recently, however, the relative isolation of the region from the rest of the country has played a role in the way its literature has been seen as being endemic to its geography – speaking only to Northeastern sensibilities and no other. This is an erroneous assumption which writers from the region have long and vehemently opposed. Writers like Robin Singh Ngangom and Mitra Phukan, for instance, insist that literature from the Northeast is a universal literature.

The stories chosen here include those written by established writers as well as newer voices. As such, these stories represent future possibilities as much as established traditions. Stories by newer writers such as Rishav Kumar Thakur, Ramzauva Chhakchhuak, Mainu Teronpi, Mayookh Barua, Gankhu Sumnyan, Saweini Laloo, and Lede E Miki Pohshna have been included to add fresh perspectives to literature from the region. However, in making these choices, it was ensured the stories complied with the key requirements of what a good short story should be. Like any other short story, the stories here represent an idea in distilled form.

They also, as with most short stories, abide by the unity of theme, length (averaging about 2,500 to 3,000 words), and plot. Their infinite stylistic variety and the possibilities they present, however, show how difficult it is to club literatures from the Northeast under one umbrella. Nonetheless, an attempt has to be made to trace the historical evolution of the short story in the region. This is done so that it might enable readers who are unfamiliar with the region’s history and its literature to grapple with the wide-ranging themes that are explored in this volume. But first, I shall digress into a short account of the narrative influences in the region’s short story, which will provide some insight into the formal characteristics of the stories in this volume.

The short story genre in the Northeast emerged from two interrelated phenomena – the oral traditions in the region and the rise of print culture. The former exerted, and continues to exert, considerable influence on the short story in the region. Storytelling traditions and forms such as the khanatang and puriskam of the Khasis, the gozam colo and cubun’ colo of the Bodos, the Mosera Kihir of the Karbis, and the wari leeba of the Meiteis inform the stories of writers from their respective communities in terms of content, form, tone, and register. Relying on memory, community, and generational cultural traditions, oral storytelling often reaffirms group identity as well as everyday lived experience. Oral storytelling traditions also reflect socio-economic realities. With no perceivable authorship, oral stories belong to high and low, rich and poor alike. They encompass proletarian ideals of what the world is and lessons on how it should be. This is especially serviceable to people from working-class lineages and communities who, with limited access to modern education, rely on oral narratives to teach their children the ways of the world.

Print culture in the Northeast emerged from a contested history in relation to the region –colonialism. Colonialism brought about the standardisation of languages, the effects of which are still felt today. It also introduced English as a lingua franca in the region. Most of the stories featured in this volume are written in English. As many have observed, the global reach of English is one of the reasons why writers from the Northeast choose to write in the language.

The other reason is the entrenchment of colonial education and Christianity, especially in the hills. The proliferation of missionary schools in the nineteenth century meant that several generations of people indigenous to the Northeast were educated in English worldviews. As such, the early literature in the Northeast was tinged with an English sensibility. Because of this, many writers from the Northeast do not consider English to be a foreign tongue or a second language. “I move in and out of both languages quite easily,” remarks Esther Syiem on her linguistic inheritance, that is, Khasi and English. Short stories in English written by writers who belong to the Northeast, however, were slow to make their appearance. The first known collection of modern short stories in the English language, Stories of a Salesman by Murli Das Melwani, was only published in 1967. It is in the local languages that the first short stories from the region were printed.

States such as Manipur and Assam have a long tradition of literature in the local languages, from well before the coming of the British. The significance of these literary traditions, however, was only acknowledged with the establishment of universities in the region during the mid- to late-twentieth century. At the time when they were written, these texts were only accessible to a select few such as the priestly class of these societies.

With the arrival of the modern printing press in the region, literary works in the local languages became accessible to the civilian population. Local printing presses such as the Ri Khasi Press in Shillong, established in 1896, the Molung Printing Press in Molungyimsen in 1884, and magazines like Jonaki in Assam were instrumental in taking the short story to the masses. “Litikai”, the first Assamese short story written by Lakshminath Bezbarua, for instance, was serialised in Jonaki in 1889. Dictionaries that were published and made available in local languages strengthened their standardisation. The complexity of linguistic inheritances makes the translation of such stories into English extremely difficult.

The translatability of Northeastern lifeworlds into English is something that has captivated generations of writers and translators from the region. Like any language in the world, languages in the Northeast carry the cultural and historical legacies of the people who use them. Most writers, like Syiem, include words in their mother tongue when there are no equivalents for the same in English. This seems to be a sound practice where stories written in English are concerned. The inclusion of local terms and phrases along with words in English makes the language in which the stories are written a queer language, trespassing norms of purity, and inclusive of marginalised identities too. How this translates into the acceptance of queerness in day-to-day living, however, remains debatable, as three stories in this anthology show.

The other, more immediate form of translatability is the direct translation of stories originally written in the local languages into English. This appears to be a more arduous task since something of the original story always gets lost while being translated. That being said, something always gets lost in the translation of stories into print since stories are, by their very nature, selective regarding what about the Northeast is committed to remembrance.

The stories in translation included here tend to avoid many of the pitfalls of translated works, such as clichés and archaisms. Even when the narratives are set in a certain time and place that are not of the present, the translators here have avoided hackneyed phrases and archaic language, giving the stories a contemporary flavour. My own inability to read the translated stories in their original language has made me realise the importance of translators who are rarely, if ever, acknowledged. I am grateful to Soibam Haripriya, Aruni Kashyap, Stuti Goswami, Ellerine Diengdoh, and Gayatri Bhattacharyya for bringing the stories from the Northeast to the world through their translations. They have achieved no mean feat.

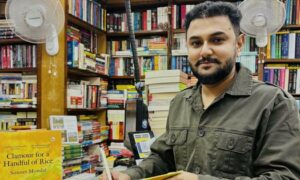

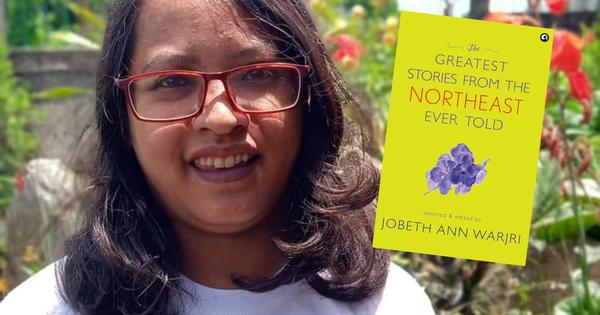

Excerpted with permission from the Introduction to The Greatest Stories from the Northeast Ever Told, edited by Jobeth Ann Warjri, Aleph Book Company.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting