On August 1, 2025, Rahima Khatun, 74, lost her right to vote. The Election Commission of India struck her off the voter list because it believed that she had shifted away permanently from her village, Ansari Tola, in Bihar’s Purnia district.

But after we made a few inquiries in the village, she emerged from her small brick house and sat down in a chair in the courtyard. She had been here all this time.

Her son Mohammad Aslam explained that the local booth level officer, or BLO, had delivered Rahima’s enumeration form to another village in July. “By the time the form came back, the deadline had passed,” he said. “Then two men from the local administration came and told me that her name had been deleted.”

The Election Commission is drawing up a new voter list for Bihar from scratch. This list would be the basis of the assembly elections in the state later this year.

The exercise, called a special intensive revision, began on June 25, with booth-level officers tasked with collecting enumeration forms from 7.89 crore voters in the state within 31 days.

On August 1, the poll body produced a draft list, which included the names of everyone in Bihar who had submitted the enumeration form. It excluded 65 lakh voters in the state – nearly 8% of the electorate.

Among those excluded is Nujraj Parveen, 36, who runs a small grocery shop beside Rahima’s house. Parveen did not know about her exclusion, nor that the EC had done it because she was labelled “absent”.

“I have been in this village since I got married more than a decade ago,” she said agitatedly. “I have voted in all elections since then.”

Parveen’s form is still with her. She said that the BLO never came back to collect it, contrary to SIR guidelines. The BLO, Parvez Alam, said that he had visited Rahima and Parveen’s home more than once but had not found them there. “It was the time of Muharram and there was a fair in the local village,” he said. “They must have gone there.”

Such stories are common across Seemanchal, Bihar’s poorest region, where voters in nearly every village have lost their vote without any basis. They are not dead, absent, enrolled in multiple places, nor have they migrated. And yet, the EC’s hastily conducted revision of electoral rolls has cut them out of the democratic process right before the state elections.

For this, some voters squarely blame the BLOs, the EC’s on-the-ground officials, who were just given a month to collect the forms. But others see a larger design to exclude those who do not vote for the Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance.

Before we travelled to the region in mid-August, our analysis of the draft list had revealed certain patterns of exclusion – we found more women had been excluded than men and Hindus had been excluded over and above their share of population in the region’s Muslim-dominant districts.

On the ground, however, while reporting from villages reporting the highest exclusions, we found greater complexity: not all exclusions were wrongful exclusions. In a village dominated by Hindu upper castes, excluded voters were those who had migrated out. In contrast, wrongful exclusions were easy to spot in Dalit hamlets. But they peaked in villages with Muslim voters.

Ansari Tola, Banmankhi assembly constituency

Ansari Tola falls in Banmankhi assembly constituency. It had 2,689 registered voters in June this year, most of them Ansaris, who are listed among Bihar’s backward classes. The voter roll revision has deleted 589 voters from the village – a staggering 22% deletion rate.

Mohammad Nabi Hasan, 63, has lived in the village all his life. When Scroll read out the names of 20 excluded voters at random, he said that about half of them were living in the village. “We have never been a village that votes for the NDA,” he said. “On election day, the administration tries its best to prevent us from voting. This exercise is now being done to remove us [from the voter list] altogether.”

Rahima Khatun’s son, Aslam, had heard about the EC’s claim that the SIR would not leave out any legitimate voter. “So what should we make of this,” he asks, pointing to his mother. “This is great injustice.”

Bajraha village, Dhamdaha assembly constituency

The bazaar closes soon after sunset in Dhamdaha, a busy town an hour east of Purnia. But a stone’s throw away from the bazaar, a large hall in the campus of the local administration was booming with the voice of an angry man.

It was sub-divisional magistrate Rajeev Kumar, who had been berating an audience of more than a hundred people sitting quietly before him. They were BLOs from the Dhamdaha assembly constituency, whom Kumar holds responsible for the constituency’s lag in collecting SIR paperwork from voters.

The deadline of September 1 was just two weeks away and a third of the electorate was yet to submit documents to prove that they are Indian citizens.

“What is the point of this?” remarked one of the BLOs, opting to stay anonymous. “He has been shouting for hours and this happens multiple times a week. First they burden us with an impossible amount of work and then scream about why we’re struggling to finish it.”

When the Election Commission intensively revised Bihar’s voter list in 2003, it had set aside a whole month to train on-the-ground officials before the exercise, according to the Indian Express. Other revision orders from 2004 show that in this period, officials were given maps of their respective areas and trained on how to carry out door-to-door enumeration.

This year’s SIR has not included a dedicated training period. The BLOs’ training was cramped within June 25 and July 26 – the duration of the enumeration process.

The poll body has also modified the exercise midway. In the official order, BLOs were asked to collect forms and citizenship documents before July 26. But on July 5, the EC said that submitting only the enumeration form would be sufficient in this period.

The resulting confusion has had telling consequences. In Bajraha village, 13 kilometres south of Dhamdaha, the BLO is a man named Murari Prasad Rakesh. But Prasad has been severely ill for months, and so the work has fallen on the shoulders of his wife, 35-year-old Meera Devi, who has little experience, and an assistant who does not live in the village.

Meera Devi told Scroll that her superiors in the local administration had asked her to not only collect enumeration forms, but also proof of citizenship, before July 26. “I could not collect the proof of many people who live here, especially among the Harijans” said Meera Devi, who comes from the Mali caste, listed as an extremely backward class in Bihar. “That is why many names have been cut.”

Bajraha’s electoral roll had 1,253 voters before the SIR began. The revision cut out 408 voters from it – a deletion rate of 33%.

Among the excluded are voters who have died and women who moved away after marriage.

But many young men from the village’s Musahar hamlet, a settlement of Dalits, have lost their vote because they are working in Punjab and could not send their paperwork to Meera Devi. Like Ansari Tola, even voters who are alive and living here have been removed.

One of them is Ratan Rishi, 65, a frail man from the Musahar hamlet who spent most of his life as a landless tiller. The EC’s exclusion list says that Rishi was “absent” from the village during the enumeration. But the old man said he was not aware of the exercise. “All this is the government’s work. How would I know?” he asked. “I feel bad [about the deletion]. One can’t feel good about it.”

Meera Devi and her assistant said that they had asked Rishi to fill the form and submit his documents, but the old man simply denied this.

Not far away from Rishi’s house, Fado Devi, 40, has been marked “shifted” and removed from the voter list. She too did not know this. “What should I do now?” she asked, confused.

Both Rishi and Fado Devi do not have any of the 11 documents that the EC has prescribed to remain on the final voter list that will be published on September 30. Their neighbour, Satyanarayan Yadav, believed that it was an unfair demand.

“The BLOs say that if you don’t have documents, a bank passbook would do,” he said. “But these people are so poor that they do not have enough for a day’s meal. Would they work to earn their bread or go to the bank to open an account?”

Chandeli Karmanchak village, Rupauli assembly constituency

It is not only in Dalit or Muslim hamlets where exclusions run into hundreds. In Chandeli Karmanchak village in Rupauli assembly constituency, a hamlet of Brahmin and Thakur voters, 408 voters have been deleted from one polling station.

But Scroll could not find a single case of wrongful exclusion here. Rajesh Kumar Jha, the husband of the local ward member, went through a list of excluded voters and said that most of them had migrated to cities like Delhi, Mumbai or Patna.

But there were complications, especially for women voters, Jha explained. “Women who came to our village after marriage are not able to procure documents from their parents’ homes,” he said. “The 2003 voter list is especially hard to access. I don’t think they’ll be able to prove their citizenship before the September 1 deadline. It will have to be extended.”

Outside the village, in hamlets where the extremely backward castes and Dalits live, most of those excluded had died or left the village years ago. “Most people among Kevats and Musahar castes don’t have land so they have no reason to stay here,” said Deepak Kamti, a local. “Moreover, someone dies here every other day. One man died just this morning of a snakebite.”

Belka village, Amour assembly constituency

A thin road splits Belka village into two in Amour assembly constituency, about 50 km north of Purnia. On the right side is a settlement of Kulaiya Muslims, an extremely backward class. On the left are homes of Bangla-speaking Surjapuri Muslims, one of the state’s backward classes.

Of the 2,667 voters registered in Belka before the SIR, 543 voters were deleted during the exercise – a deletion rate of 20%.

There are wrongful deletions in both sides of the village, but a bulk of them are from among the Bangla-speakers. This includes Sanjari, 54, and her daughter, Musarrat Jahan, 23. Three of their neighbours, Dil Jahan, 22, Mohammad Mujahir, 36, and Kuresha, 52, have also been wrongfully excluded.

The reason given by the EC is that all five were “absent” during the SIR. But like other villages we reported from, Belka residents said that this was not true.

“The mukhiya [village head] told me that my name has been deleted,” said Sanjari. “I have voted here all my life. This time, I gave the signed form to the BLO and yet he cut out my name. He should add it back.”

Mujahir, who has worked in Saudi Arabia, had even submitted his passport along with the form – one of the eleven documents considered as proof of citizenship by the EC.

“I was assured that my name would be included, but I checked with the ward member when the draft list came out, and he said that my name has been deleted,” he said. “Many people here have been deleted wrongly and they don’t even know about it.”

The BLO, Mohammad Shayaque Anwar, told Scroll that the blame for wrongful exclusions rests on the villagers. “They did not submit their forms on time, that is why they were left out,” he said. “I visited their homes more than once. Many of them kept asking me to come tomorrow but never submitted the form.”

In the Kulaiya side of the village, ward member Mohammad Muzaffar Alam blames BLOs and their apathy. “They are not visiting people at their homes,” he claimed. “Unka janta se sampark nahi hai.” They don’t have outreach among the people. “This is a dereliction of duty.”

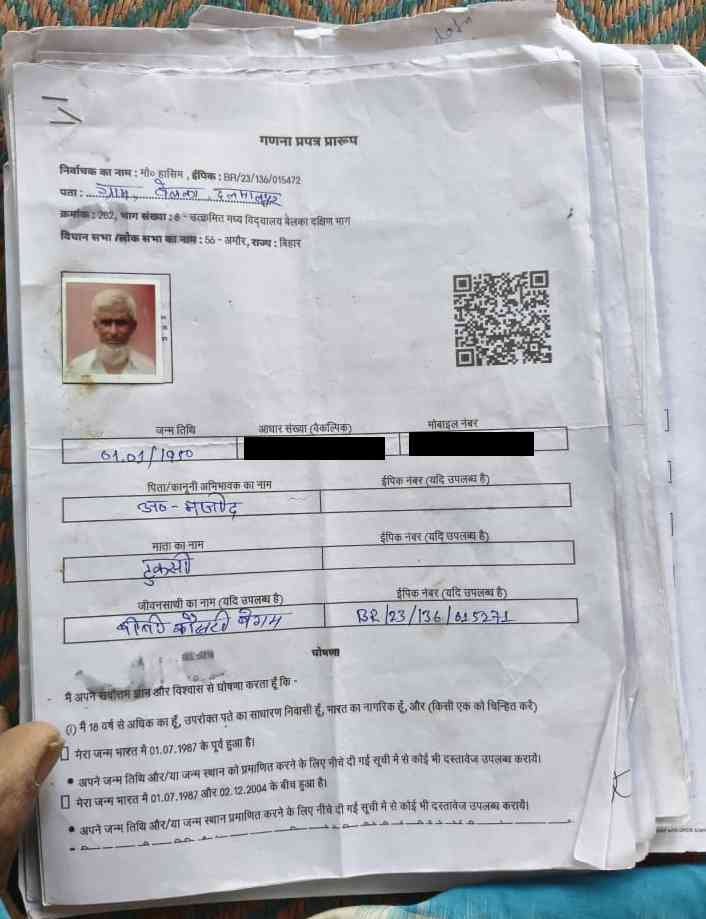

When we met Alam, he was trying to help 61-year-old Mohammad Hashim, who submitted his form with the BLO, and which the BLO shared with Alam. Yet, Hashim has been excluded and marked “absent” by the EC.

The local BLO, Abu Kalam Ansari, declined to speak with Scroll.

Despite wrongful exclusions across Seemanchal, disenfranchised voters in the region have an opportunity to re-enrol into the voter list by submitting form six to the EC before September 1 – a document usually used by first time voters. This form will have to be appended by an Aadhar card and proof of citizenship.

On August 30, two days before this deadline, Bajraha BLO Meera Devi’s assistant, Ashwini Yadav, told Scroll that neither Rishi nor Fado Devi have filled form six. “They don’t even have Aadhar cards,” he said. “I have been to their house more than once and offered to get their Aadhaar made. But they are not cooperative.”

In Ansari Tola, Rahima Khatun and Nujraj Parveen have filled their form six but the BLO, Parvez Alam, has not submitted them yet. Alam said he would submit the forms after September 1. When told that September 1 was the deadline, Alam said that he was not aware of it. “You see, we have been put to this job without any training,” he added.

In Belka, BLO Mohammad Shayaque Anwar claimed that he had collected form six from all wrongfully excluded voters and filed them with the local administration. “They will be added back,” he said.

The real test that awaits Bihar’s voters begins on September 1, when a few hundred bureaucrats will screen more than the state’s seven crore voters for their citizenship. If the enumeration stage is anything to go by, a significant chunk of the state’s electorate will be left out of the electoral system. As a result, they will not be able to vote in the assembly elections later this year – something they have done all their lives.

All photographs by Aryan Mahtta.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting