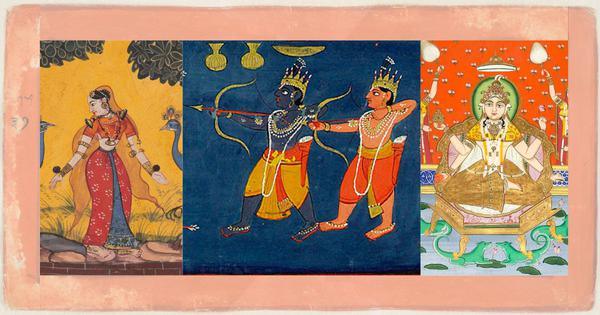

Against a deep blue backdrop, sword-wielding demons attempt to disrupt a sacred ritual. Ram, who is dressed in a yellow dhoti and rendered in a shade of blue distinct from the background, rains arrows on them. Lakshmana ably assists him. The demons seep vermillion blood.

This 18th-19th century Rajasthani miniature, Demons Approaching Rama and Lakshmana at a Fire Ceremony, does not just capture a charged moment from the Ramayana where ritual and battle converge. It is a snapshot of global trade and cultural exchange in the 1800s.

The dominant pigment in the painting is Prussian blue, invented in Berlin around 1706. It was soon manufactured across Europe, and exported to Asia. In Japan, Hokusai used it to create The Great Wave of Kanagawa (1831) – the iconic image that is a popular screensaver on digital devices today.

The Indian yellow is a local pigment, once produced primarily in Bihar from the urine of cows that were fed only mango leaves. Before the British banned the production of Indian yellow in the early 20th century, the pigment had made its way to Europe.

In this Rajasthani painting, the Prussian blue and Indian yellow come together to create the dark green of the holy man’s sash and one of the demon’s shorts.

The chemical composition of the pigments used in this work and more than 200 other South Asian and Himalayan paintings and manuscript folios is now available at the click of a mouse, thanks to Harvard University’s Mapping Color in History initiative.

Focusing on the materials and histories of South Asian art, its searchable database allows users to explore the paintings by title, pigment, keyword, date, region and more.

The initiative, which began in 2018, is the product of a transcontinental collaboration between conservators, computing specialists and art historians among others. The database offers a new way to read history – through colour.

The mystery behind a blue hue

It all began with a pigment puzzle.

In 2016, a conservation scientist at a museum in Boston detected cobalt in a 15th-century Jain manuscript. But smalt, a cobalt-infused blue glass pigment, was manufactured in Europe and exported to Asia only from the 17th century. The assumption was that conservationists had retouched the colour.

It piqued the interest of Jinah Kim, professor of Indian and South Asian Art at Harvard University, who was gathering data on pigments as research for her book on the material history of Indian painting. Kim wondered, “Did everything have to come from Europe? What do we know about actual pigment usage in India at this time period?”

Soon after, Katherine Eremin, Senior Conservation Scientist at Harvard Art Museums, cracked the cobalt pigment puzzle.

Eremin narrowed down the origin of the glassy cobalt pigment using its geochemical signature – it had trace elements associated with a cobalt mine in Kashan in Iran. The deep-blue smalt pigment, assumed to be European, most likely originated in Asia. She analysed a 17th century Rajasthani painting in the Harvard collection and determined that it had smalt which originated in Europe.

Kim’s larger question remained: was there an indigenous system of colorants in India we know nothing about?

Long before synthetic hues, artists sourced their colours from a range of mineral pigments, plant-based dyes and insect-derived colorants. To identify and analyse these pigments is to understand the material core of art.

Consider the colour green in Indian miniatures. Is it a blend of blue and yellow pigments, as in Demons Approaching Rama and Lakshmana at a Fire Ceremony? Or is the green from beetle wings? If copper is detected in a painting, does this vibrant green come from malachite or atacamite?

A suite of microscopy, imaging and spectroscopic techniques, which use light to decode the molecular composition of materials, allows researchers to determine the chemical makeup of pigments. Newer spectroscopic techniques can be used to analyse layered paintings without sampling or contact. Such detailed analyses can guide conservation strategies, inform restoration choices and help authenticate valuable paintings.

Past and present

What you cannot learn from a dead artist, or glean through an analysis of paintings using instruments, you can ask a living practitioner, says Kim. Today’s artisans often rely on recipes and techniques passed down through centuries.

There is value in understanding the process. This concept of artistic traditions being passed on from generation to generation is enshrined in The Intelligence of Tradition in Rajput Court Painting, by Molly Emma Aitken.

In 2021, conservator Anjali Jain, the India-based research manager of the Mapping Color in History team, visited the workshop of Babulal Marotia, an award-winning miniature painter based in Jaipur, to document this living tradition.

Marotia says he chooses pigments based on colour and tone. Mixing colorants with gum Arabic gives them a smooth, glossy finish that allows for fine layering. Marotia paints on handmade paper with an ultra-fine brush, no longer made of squirrel hair.

As a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard’s Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, material scientist Celia Chari had analysed 42 colorants from Marotia’s palette. A little over half of them matched pigments found in 16th-century Indian manuscripts such as yellow harital (arsenic sulfide), red hinglu (mercury sulfide), and kajal (lamp black). The gentle red of safflower was no longer part of the palette, nor was the translucent maroon of lac, derived from a “lakh”, or multitude of Kerria lacca insects.

Expensive ultramarine (lajwarda), a blue mineral pigment once prized for its depth and luminosity, has disappeared but plant-based indigo is still in use. “Limited availability and changes in the modern supply chains make it difficult – and even financially unviable – to source the exact materials being used in historic times,” said Jain.

Among contemporary pigments, Chari found Prussian blue, which has been used in Rajasthani miniatures for over two centuries now. There was white arsenolite, an inorganic compound undocumented in South Asian art, and brown barium ferrite, with no recorded use as a pigment in any culture.

If the presence of arsenic and mercury compounds in the palette raises concern, Chari says, the artist is aware of the toxicity of paints and uses thorough handwashing as a protective measure. Aesthetics guides the artist’s choice – not chemical composition.

Through this pioneering study, which was published earlier this year, the researchers have just begun to explore the materials of contemporary South Asian artists through a scientific lens. Such studies can help future conservation efforts of contemporary paintings and deepen our understanding of traditional pigments. “It is all part of a continuum,” said Kim.

Better conservation

Collaboration with Indian institutions – the natural home of the majority of old Indian paintings in all their diverse styles – is vital to study trends in pigment usage across time and geography. Most museums in India lack in-house instrumentation – a notable exception is the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai.

For most museums, transporting artwork to instrumentation centres is fraught with risk. To make the analytical techniques accessible on site, the Mapping Color in History established the Mobile Heritage Lab equipped with portable, handheld instruments.

Already, the mobile lab has been deployed for the pigment analysis of old illustrated manuscripts such as the Aranyakaparva (1516 CE) at the Asiatic Society in Mumbai. Similar studies are underway at the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum in Jaipur’s City Palace. Discussions are in progress for a similar collaboration with the Government Museum and Art Gallery in Chandigarh, home to a collection of antique Pahari paintings.

“Sometimes old objects of art are treated with such absolute reverence – they’re left alone when, in fact, research-based conservation efforts would serve them better,” said Kim. As Project Director of Mapping Color in History, she emphasises the need for analytical studies to guide informed decisions about conservation.

While conservation itself lies outside the scope of the Mapping Color in History project, the goal is to offer science-based insights to museum conservators – empowering them to make evidence-based choices that enhance the longevity of the works in their care.

An Indian miniature may arrest one’s gaze with colour but its context – scientific, cultural and lived – holds the attention of the modern viewer. Thanks to new research, traditional Indian paintings are not just being admired, they are being understood and will hopefully be better preserved for future generations .

Vijaysree Venkatraman is a Boston-based science journalist.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting