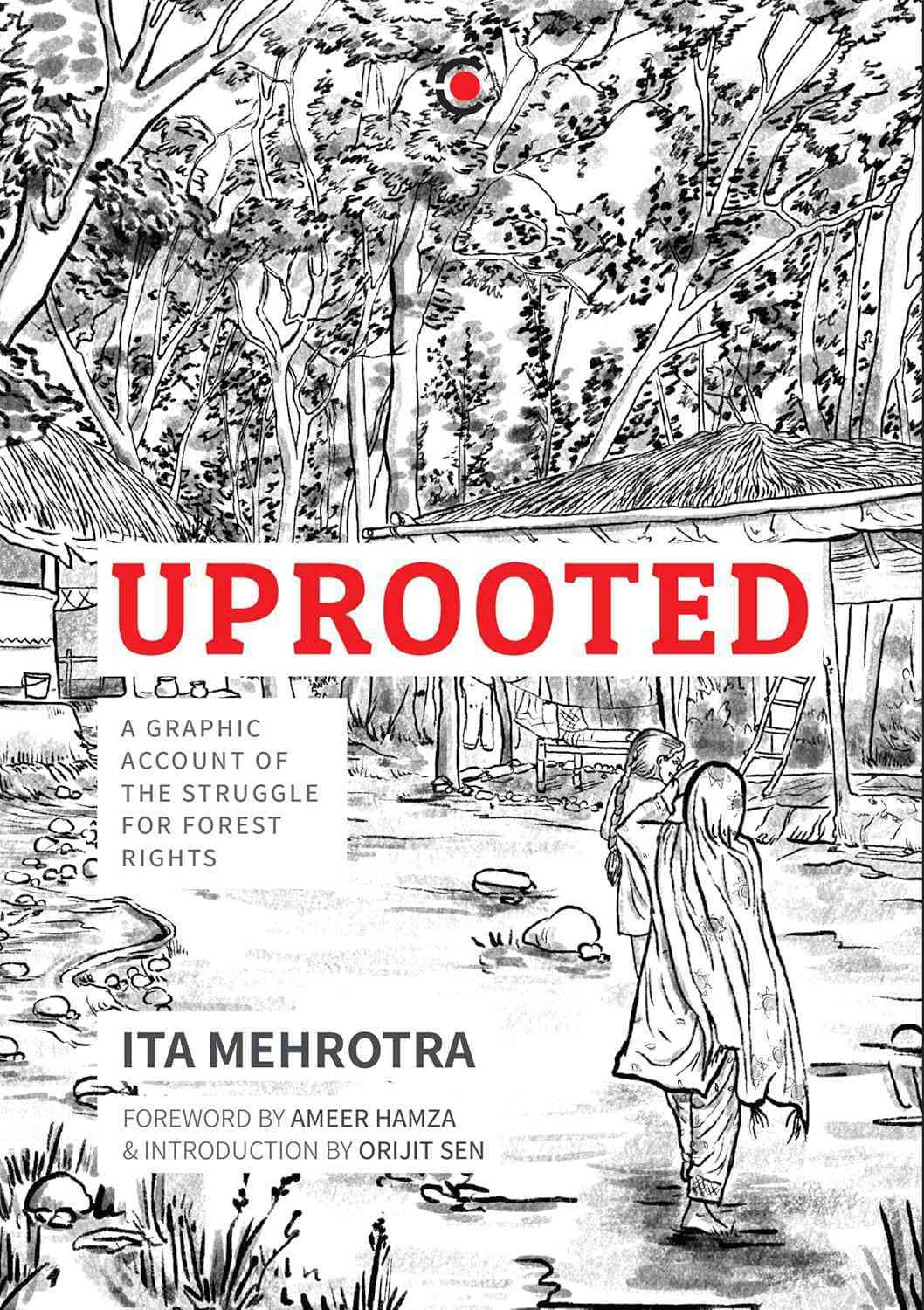

Ita Mehrotra’s debut, Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection (2021), was a product of urgency: bold, poster-like strokes, hand-lettered slogans, and the kinetic energy of a movement unfolding in real time. Her new book, Uprooted: A Graphic Account of the Struggle for Forest Rights, by contrast, is a slower, more deliberate act of witness. Its monochrome pages – still etched with the scrappy immediacy of field notes – meticulously trace the lives of India’s forest-dwelling communities, particularly the Van Gujjars. The narrative spans two centuries of displacement: reaching from colonial forest laws that barely tolerated their nomadic pastoralism to today’s neoliberal conservation projects that treat them as trespassers on land they’ve lived with for generations.

Where Shaheen Bagh documented a protest, Uprooted inhabits a generational struggle – one that predates the book’s making and will outlast its final panel. Its pages are dense with the kind of scribbled marginalia that betray long hours spent listening rather than merely observing.

Drawing with, not about

Mehrotra’s style – loose, expressive, and deliberately unpolished – mirrors the fragility and resilience of her subjects, who are also her comrades-in-arms since 2021. Faces are carved with the weight of seasons; forests creep into the edges of panels like uninvited memories. Panels are windows, yes, but also thresholds: doors left ajar reveal forests, windows frame landscapes that are as much a part of the Van Gujjars’ interiority as their daily routines.

The absence of colour remains not just an aesthetic and a commercial choice but also an ethical one – a rejection of the picturesque in favour of the palpable. Black-and-white forces the eye to engage with texture, with the weight of a line, with the way someone’s story is completely changed by their relationship to the land. These are drawings, not paintings. They are a means to an end. Amazon no longer owns Westland. Their power lies in their incompleteness.

The book’s politics mirrors this structure. In an unpublished section of a 2022 interview with this reviewer following the publication of Shaheen Bagh, the cartoonist spoke of how comics “force you to be honest about the narrative you’re telling” because “image and text tussle with each other – there’s nowhere to hide.” Here, that tussle becomes a form of solidarity. The Van Gujjars’ historical predicament is narrated by those living with and contesting its legacy: legally, economically, and ecologically. Eschewing a single protagonist, she again constructs a constellation of voices – women, elders, children – in a narrative that keeps moving as naturally as the community whose lives and displacements it reports on.

The Van Gujjars are her only interlocutors. Their art, culture, relationship with animals, zest for life in the forest, and unflinching resolve to hold on to their land and livelihood are woven into the volume’s fabric. The only forest officer given voice in the narrative is retired and a Van Gujjar himself. The best he can do is stay silent on the matter. This is deliberate. Mehrotra’s project is not balance but redress – to recenter voices that official histories still need to heed. Her comics are “locators,” as she once described Shaheen Bagh: nodes in a network of resistance, demanding readers to interrogate their own complicity. Such propaganda is refreshing in a scene whose indie comics often borrow North America’s underground aesthetics but conveniently forget the political edge that such approaches are born from.

The jungle is a charged space in Indian comics: from the pastoral idyll only occasionally disturbed by demonic activity in Amar Chitra Katha to the flattened feminist mysticism of Amruta Patil and Devdutt Pattnaik’s Aranyaka (2019, also originally published by Westland). Mehrotra rejects both. Her forest is neither Eden nor allegory, it’s a working landscape. The maps that the pages frequently break all kinds of geographies into are part of this strategy. The lettering too flits and places itself strategically into all kinds of spaces, while panels linger on spaces after conversations end, framing the forest as a social habitat rather than “protected” wilderness. This is where Mehrotra plays her part in the relay. Where Orijit Sen once mythologised the Narmada Bachao Andolan in River of Stories (1994), Uprooted renders displacement as something profoundly mundane: unending paperwork, litigation, and the ever-present horror of returning to rubble.

Comics as living documents

The Indian graphic novel, as a category, has long suffered from a crisis of legitimacy – desperate to be taken seriously while shackled to market expectations of what “serious” looks like. Consider some of the dominant templates: the mythological reboot, the autobiographical trauma narrative, the middlebrow historical, or the high-brow anthology. These are works that perform their gravitas through polish – lush watercolours, meticulous research appendices, the sheen of an MIT grant.

Uprooted continues Mehrotra’s innocuous project of showing how this machinery may one day be dismantled. Its power lies precisely in what it lacks: a fetishised auteur gloss and the bourgeois preoccupation with closure. Orijit Sen writes the Introduction but it is the founder of the Van Gujjar Tribal Yuva Sangathan, Ameer Hamza, who gets top billing with the foreword. Mehrotra’s pages retain the raw urgency of her early zines – smudged pencils, erratic lettering, panels that sometimes bleed into each other like overlapping testimonies. This isn’t a book designed for literary festivals or Western academia’s “Global South Comic” syllabi, even though I am sure it will find its way into these hollowed spaces. It’s a combustible artefact, meant for classrooms and community halls, spaces where Mehrotra’s own praxis took root. Where Sarnath Banerjee’s Corridor (2004) once turned Delhi into a playground for postmodern irony, and Appupen’s chronicles from Halahala continue to render capitalism as an all-too-present surreal allegory, Uprooted insists on something radical for comics from India: that the medium’s purpose may also be to document and delineate, not just decorate.

Uprooted cannot resolve things. There’s no triumphant climax, no single corporeal villain to boo. The Van Gujjars resist becoming a one-volume cause; their solidarities more than the sum of their struggles. Even the Forest Rights Act – a progressive law on paper – is shown as a bureaucratic maze. This logjam of irresolution connects Mehrotra to the scabrous comics of fellow artists like Anand Pagalkutta, with whom she shares a millennial understanding of asymmetry as our national condition. The rough edges that abound in their comics are perhaps better suited to tracing the contours of a nation that may yet be reclaimed in between the gutters.

Uprooted: A Graphic Account of the Struggle for Forest Rights, Ita Mehrotra, Context/Westland.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting