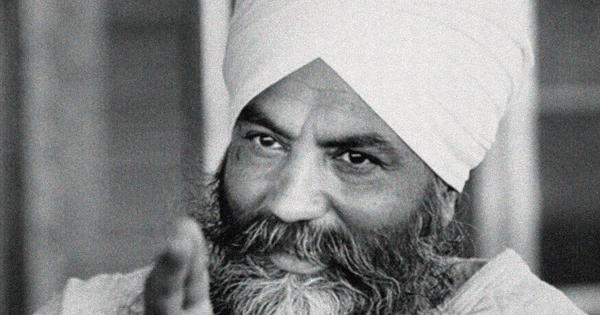

If there is one single name that is today associated with the practice of Kundalini in the marketplace of popular spirituality, it is Yogi Bhajan (1929–2004). Born Harbhajan Singh Puri to a Punjabi Sikh family, Yogi Bhajan arrived in North America in 1968 and quickly established himself as a teacher of yoga. The myth behind the man tells of Yogi Bhajan’s tutelage, as a young boy, under a Sikh spiritual master named Sant Hazara Singh, who, through strict discipline and instruction so stern it bordered on brutal, inducted his student into the martial art of gatakā as well as the spiritual disciplines of “White Tantric Yoga” and “Kundalini Yoga.” The discipleship reached its conclusion when the young Harbhajan was only sixteen, at which point Hazara Singh confirmed him a master of Kuṇḍalinī and declared that student and teacher were not to meet again. This made Yogi Bhajan the last link in the “Golden Chain” of an esoteric lineage of Kuṇḍalinī practice, stretching back to time immemorial.

However, as Philip Deslippe has shown, the claims to lineage and antiquity made by Yogi Bhajan and canonised by his disciples are historically questionable at best. This is not a unique fault. Any guru on the landscape of modern yoga who has tried to evoke ancient tradition to prop up their method of postural yoga has done so on shaky ground.

The fact of the matter is that modern postural yoga – like modern anything – is simply not that old a formulation. This, in our view, does not invalidate the methods themselves. But we should perhaps be wary of the ways that claims to a lineage of ancient wisdom buttress claims to authority and authenticity.

There is an earlier version of Yogi Bhajan’s origin story, which traces his enlightenment to a touch on the forehead by a different teacher, Maharaj Virsa Singh, a Sikh teacher living in New Delhi to whom he was introduced by his wife (Virsa Singh’s original devotee) in the late 1960s when he was working as a customs officer at the Delhi airport. In his early days in Los Angeles, Yogi Bhajan claimed that it was Virsa Singh who had sent him to the West after ceremonially presenting him with his sandals, a mark of the guru’s grace.

Deslippe has demonstrated that this, too, is only partially historically verifiable and – at best – not the full story. The physical elements of what would become Yogi Bhajan’s hallmark “Kundalini Yoga” practice, which is indeed quite distinct from other popular forms of modern postural yoga, likely came from a Hindu yogi and physical trainer named Swami Dhirendra Brahmachari. Dhirendra Brahmachari’s system fused elements of haṭha yoga with an indigenous system of physical exercises often used by wrestlers known as vyāyāma (which indeed translates to something like “exercise”) to produce what he called “Sūkṣma Vyāyāma” (Subtle Exercise).

As multiple scholars of modern yoga, including Joseph Alter, Jerome Armstrong, Mark Singleton, and Jason Birch, have demonstrated, such remixing of haṭha yoga methods with other forms of physical development, including vyāyāma, was a common feature of Indian physical culture going at least as far back as the eighteenth century. The rhythmic swinging and rotating motions that appear so distinctive to Yogi Bhajan’s “Kundalini Yoga,” and which he refers to as kriyās, can also be found in the “Energisation Exercises” that preface Paramahansa Yogananda’s “Kriya Yoga” as the method still taught by his organisation, the Self-Realisation Fellowship.

To formulate these (at least three decades before Yogi Bhajan or, indeed, Dhirendra Brahmachari), Yogananda likely drew on European forms of physical culture as much as on indigenous Indian ones. Yogananda’s Kriya Yoga is, of course, a method of raising Kundalini (and indeed one that far more closely resembles the older medieval fusion of tantric Śaiva-Śakta laya and haṭha techniques). However, Yoga-nanda viewed the calisthenic Energisation Exercises as largely preparatory to Kriya Yoga; indeed, he never referred to them as “yoga” proper, nor as kriyās more specifically. This, to be clear, does not mean one cannot do so. Tradition is an evolving thing. But such areas of overlap between innovators also make one wonder how the current “market share” on Kundalini, kriyā practice, and yoga at large might have been shaped differently.

Yogi Bhajan’s presence as a preceptor of Kundalini is chiefly embodied by the Healthy, Happy, Holy Organisation, commonly known as 3HO, as well as the Kundalini Research Institute. There is also Sikh Dharma International, founded in 1973 as the Sikh Dharma Brotherhood and later called Sikh Dharma for the Western Hemisphere, which represents the more overtly religious face of Yogi Bhajan’s guru persona. Besides these, Yogi Bhajan left behind a veritable juggernaut of capitalist ventures, assembled under the name of Khalsa International Industries and Trades.

All in all, the man had a hand in creating seventeen businesses, ranging from beauty products to a security firm. One of these was the American tea brand, found today on the shelves of nearly every mainstream supermarket, known as Yogi Tea. The tags attached to its tea bags still feature select words of wisdom attributed to Yogi Bhajan. These facts may seem like unrelated trivia, but they are actually crucial to understanding the cultural impact of “Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan.” To Yogi Bhajan, Kuṇḍalinī was a brand, and it was one he went about developing with all the acumen of a businessman, keeping a strategic eye on image and competition.

Yogi Bhajan’s devotees, and so, therefore, many of the top teachers of his Kundalini Yoga, are instantly recognisable. They are turbanned men and women – the latter being unusual if not wholly unprecedented from an ethnically Punjabi Sikh standpoint – dressed all in white (also culturally idiosyncratic). Teachers who place themselves in Yogi Bhajan’s lineage are careful to specify that what they are representing is Kuṇḍalinī yoga “as taught by Yogi Bhajan.” On the one hand, of course, this implicitly allows for the existence of many different types of yoga and methods of engaging with Kuṇḍalinī. On the other hand, however, it serves to further reinforce the link between the otherwise generic notion of Kundalini yoga and the specific “brand” associated with Yogi Bhajan’s name.

Yogi Bhajan represents the split between a guru as the charismatic leader of a community – the tightknit body of devotees that creates the social conditions rife for abuse and enough whispers of “cult” to inevitably yield a documentary exposé once the dust has settled – and the popularising brand mascot. And Kundalini Yoga as taught by Yogi Bhajan has outgrown the tarnished legacy of its founder enough that it seems likely to survive regardless of what happens to the community that first supported it. Its relatively simple rhythmic movements, which become challenging due to the length at which one must repeat them, combined with the shallow and rapid diaphragmatic breathing known as bhastrikā (sometimes also known as “bellows breathing,” but named “Breath of Fire” by Yogi Bhajan) are distinctive among popular varieties of things called “yoga” today. Again, this is not to say that they are entirely original or wholly unprecedented on the yoga scene, but they have become a recognisable part of the brand. Moreover, the identification of Yogi Bhajan’s brand with Kuṇḍalinī practice in general is likely to act as a continuous lifeline, despite the fact that the method diverges from most other current forms of Kundalini-oriented practice.

This is the ingenious key to Yogi Bhajan’s approach. From the start, it billed itself as generic even as it was highly specific. “You may have heard of transcendental meditation and integral meditation; there are many labels,” says Yogi Bhajan. “Just as there are for mustard seed: yellow mustard seed, sunflower mustard seed, Sun Valley mustard seed, California mustard seed, Wisconsin mustard seed, New York Mustard seed; mustard seed is mustard seed. Similarly, different techniques of yoga have been given different names. Hatha yoga has the same end. Bhakti, shakti, gian [i.e. jñāna], karma yoga – all have the same end. To raise the dormant power of infinity in the man; that’s all.”

Of course, to assert that all yogas lead to Kuṇḍalinī awakening is a move we have seen before. This was the position taken by Vivekananda, Sivananda, and even (in his own way) Aurobindo. It is also, as we will soon see, very much like the stance of Muktananda with regard to his Siddha Yoga. However, while Yogi Bhajan explicitly acknowledges the multiplicity of methods, his teachings (and, not unsurprisingly, the arguments of his disciples) imply again and again that it is his method that is superior and his understanding that is correct. For example, the 3HO contribution to Kundalini: Evolution and Enlightenment, a collection of available sources on Kundalini edited by John White and published in 1979, is incredibly strategic in its framing and subject matter. The piece, aptly titled “Exploring the Myths and Misconceptions of Kundalini,” begins with an introduction by disciple Gurucharan Singh Khalsa that offers a laundry list of condemnations: Gopi Krishna, Vasant Rele, Arthur Avalon, Joseph Campbell, Ram Dass – all of them got Kundalini wrong. (Swami Vivekananda, interestingly, gets a pass, as does Sivananda.)

Excerpted with permission from The Serpent’s Tale: Kundalini, Yoga, and the History of an Experience, Sravana Borkataky-Varma and Anya Foxen, Columbia University Press.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting