“We know that Mamata makes fake Aadhaar cards for you people,” Mehebub Sheikh recalled a police officer saying to him.

On June 9, the 38-year-old mason was at a tea shop in Mira Road, a town north of Mumbai, when the police detained him on the suspicion that he was an undocumented migrant from Bangladesh.

Mehebub, who had worked in and around Mumbai for over a decade, thought he had the documents to disprove their charges. He showed the police his Aadhaar card and voter card to prove that he was from Murshidabad in West Bengal.

But first the police and later the Border Security Force dismissed him outright. “They threw them in the dustbin,” he said, showing with his foot how a BSF officer allegedly dumped his documents in a pedal bin.

On the night of June 13, Mehebub was forced across India’s border with Bangladesh, allegedly at gunpoint, even as his family in Murshidabad scrambled to get land records and other documents.

He had been given only four days to prove that he was an Indian citizen.

A police official from the Mira Road police station claimed: “We did what we did according to the law. He was unable to provide any documents to prove his nationality.”

More than two months later, on August 22, Prime Minister Narendra Modi echoed what the police had said to Mehebub. While addressing a rally in Kolkata, he linked the problem of illegal immigration to Mamata Banerjee’s party, the Trinamool Congress.

“Those who have come here only to snatch the livelihoods of our people, those who are staying here with fake documents will have to go,” Modi said, drawing loud cheers from the crowd. “For that to happen, the TMC [Trinamool Congress] government, too, has to go.”

Modi went on to acknowledge for the first time that his government had been running, in his words, a “very big campaign” against alleged undocumented migrants.

But as Scroll has reported, this drive has led to the harassment and detention of migrant workers from West Bengal, a majority of them Muslim.

The police in several states ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party have detained thousands of migrant workers like Mehebub, and demanded that they produce documents to prove their citizenship.

The May 2 home ministry directive under which such police drives are being conducted allows for a 30-day window for local authorities in the individual’s home state to verify their citizenship status.

But, on the ground, the process has led to Indian citizens being declared foreigners and summarily expelled from the country – without a fair hearing, as Mehebub found out.

As Bengali-speaking migrant workers are detained in BJP-ruled states and accused of being illegal immigrants, Scroll travels to rural West Bengal to meet families forced to prove they are Indians. Read the series here.

‘Our ancestors are buried here’

Mehebub was born in Balia Hasennagar village into a family of very little means.

His brother, Majibur Sheikh, recounted to Scroll how the brothers braved immense hardship, working as rakhals or cowherds for more affluent residents without any pay. “They would only feed us,” he said. “That was enough for us at that time because ours used to be the poorest family in the village.”

Mehebub managed to escape – he found work as a helper at a construction site in Mumbai and quickly rose up the ranks to become a mason. He flourished in the metropolis for over a decade until the police detained him in June.

His identity documents say that he was born before July 1, 1987. According to existing Indian laws, that makes him a citizen of India, irrespective of parentage.

What he did not have was a birth certificate to prove it. The police in Mumbai repeatedly asked him to produce one.

Mehebub blamed his parents. “They were murkho, foolish, that is why they did not bother to get a birth certificate made for me,” he said bluntly. “I got each of my three children registered at birth.”

But as Scroll has reported, the criteria to detect alleged illegal immigrants in BJP-ruled states has been fairly arbitrary. For example, Amir Sheikh, a 19-year-old from Malda, was detained by the Rajasthan police and despite producing a birth certificate was forced out into Bangladesh.

In Murshidabad, his brother’s detention led Majibur to start a desperate search for the family’s documents.

It led him to his uncle, Nur Hossain Sheikh, who runs a fishing business in the Sheikhs’ ancestral village of Biprakali.

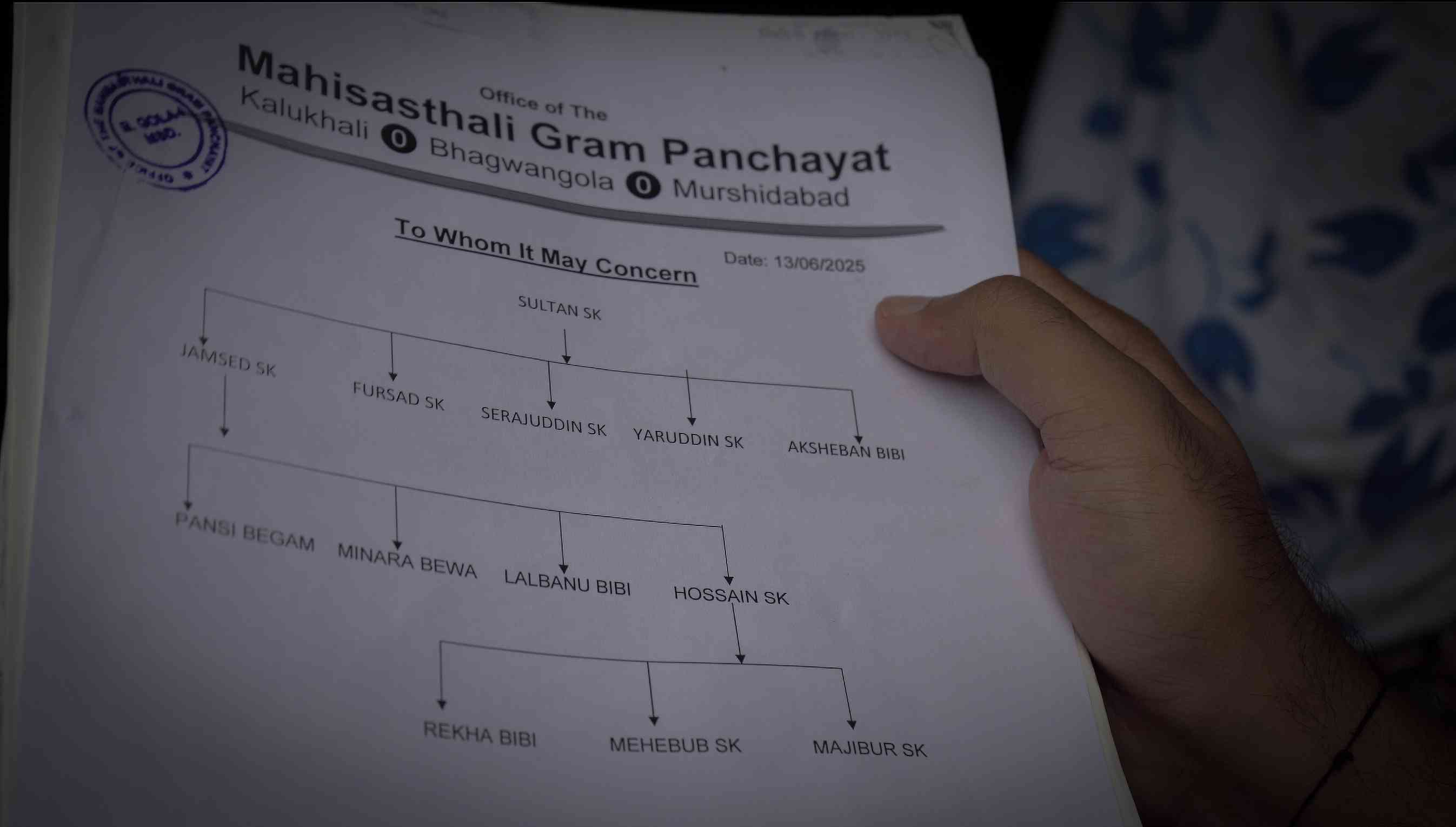

Nur Hossain was able to show local police and panchayat officials two crucial documents that helped their case. One, a land deed in the name of Sultan Sheikh, Mehebub’s great-grandfather, and the other, a voter list from the 1950s which featured the name of Jamsed Sheikh, his grandfather.

The Sheikhs have more than documentary proof of their roots in Bengal.

When Scroll visited Biprakali, Nur Hossain showed us the old home in which Mehebub’s great-grandfather and grandfather were born and the graveyard where they were all buried.

There were no tombstones on any of the graves in the compound, only raised mounds of earth to distinguish new ones from old.

Nur Hossain took us to one spot and claimed with certainty that it was where his father lay buried.

“My father brought me here when I was a young man and asked me to bury him at the feet of his father after his death,” he said. “I have requested my children to do the same with me.”

A family tree

Majibur took the documents Nur Hossain had dug up to officials of the Mahisasthali gram panchayat, which includes Balia Hasennagar.

The pradhan, Sabbir Ahammed, used the papers to quickly draw up a family tree for Mehebub.

Not only that, Ahammed accompanied Majibur to the BSF camp in Bagdogra on June 13, where Mehebub was being held, to help bring him back.

But the BSF still did not yield. “The officers at the camp did not behave appropriately with me,” Ahammed told Scroll. “They treated me with suspicion and did not even see the papers properly.”

Mehebub was taken to a forest along the India-Bangladesh border. Despite his repeated protests, he was “pushed” across. “I kept saying I am an Indian,” he said. “They hit me on my neck with the butt of a rifle to silence me.”

Scroll contacted the BSF spokesperson by email for a response to Mehebub’s allegations. The story will be updated if they respond.

But within 24 hours of being expelled, Mehebub was brought back. For this, his brother Majibur credited Samirul Islam, a Rajya Sabha MP from West Bengal and the chairperson of the state’s Migrant Workers Welfare Board.

Islam told Scroll that the chief minister’s office had taken up the issue and helped bring Mehebub back. “There was a flag meeting between the BSF and the Border Guard Bangladesh after which Mehebub was returned,” he added.

Coming to terms

But, even if he has escaped being branded an illegal immigrant, Mehebub will not be returning to Mumbai soon.

His family, fearful of a repeat of the harassment he faced, insists that he find work in West Bengal. “I keep hearing about the harassment of Bengalis in various parts of the country,” Mehebub said during a tea break at his new workplace – a construction site in a Kolkata suburb – where Scroll met him. “How can I go out like this?”

In between cups of the reddish black tea that is called “liquor cha” in Bengal, he rued the loss of his high-paying construction job. In Kolkata, he is paid a daily wage of Rs 700, when he would make Rs 1,000 a day in Mumbai. Add to that a commission that he got for bringing other labourers to the site through his contacts.

More than the money, though, Mehebub missed a sense of pride in his work.

The 38-year-old’s display picture on WhatsApp continues to show the last skyscraper he worked on.

“My employers were good. No magach maari,” he said, slipping into one of the many Bambaiyya phrases he had picked up after years in Mumbai.

The fear of NRC

In his ancestral village, while there is relief at Mehebub’s return, the episode has brought back fears of a citizenship test in the form of the National Register of Citizens.

Neighbouring Assam had updated its National Register of Citizens in 2019, after a mammoth exercise in which residents had to furnish documentary evidence of their citizenship. Nineteen lakh people had been left out of the final NRC.

Several residents in Biprakali asked us if a nationwide NRC was on the cards. There was also concern over the ongoing special intensive revision of electoral rolls in Bihar, where voters have been asked to provide citizenship documents to be able to vote in the coming Assembly elections.

Surona Bibi, Mehebub’s wife, had other concerns. The couple has fought several times over Mehebub’s desire to return to Mumbai. “I asked him to work in Kolkata, even if he earns less,” she said. “He says that he has done nothing to deserve this punishment.”

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting