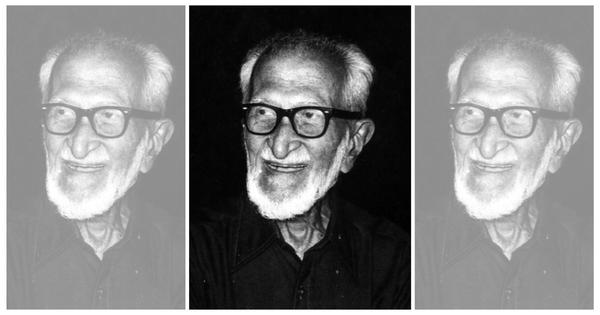

“A cock sparrow perched on the nail near the entrance to the hole while the female sat inside on the eggs. I ambushed them from behind a stabled carriage and shot the male. In a very short while the female acquired another male who also sat “on guard” on the nail outside. I shot this male also, and again in no time the female seemed to have another male in waiting who immediately stepped into the gap of the deceased husband”. This is a note written by India’s legendary birdman Salim Ali in 1906-07 when he was a 10-year-old boy.

Many years later Salim Ali wrote in his autobiography The Fall of a Sparrow, “I am rather proud of this note because though intended as a record of my prowess as a hunter and made long before I was conscious of any possible relevance, it has proved more meaningful in the light of present-day behavioral studies”.

Unexpected beginnings

More or less one year after this “experiment” Salim Ali got his first opportunity to visit the Bombay Natural History Society with another bird that he shot down. It was a sparrow again, yet a different species; a yellow-throated sparrow (chestnut-shouldered petronia). The fallen sparrow led him into a world so full of life and mysteries that kept him active for the next 80 years.

In his words, “the fortuitous incident of the yellow-throated sparrow opened up undreamt vistas for me. Thenceforth my reading tended progressively towards books on general natural history, and particularly birds. Illustrated books on Indian birds were virtually nonexistent in those days, and indeed for many years later, and there was little available to help a beginner in identifying and learning about the birds around him”.

The fallen sparrow simultaneously placed two major challenges before young Salim Ali; one, that of furthering the scope of meticulously collected data in field ornithology and two, developing appropriate user-friendly tools, as that of field guides, to popularise the field study of birds. Twenty years later, his first scientific paper on the nesting of the baya or common weaverbird was published. Salim Ali’s works and writings are a testament to the fact that good science can rise from unexpected beginnings.

According to ecologist Madhav Gadgil, “Salim Ali’s scientific work was grounded in careful, painstaking observations and recording of events in the living world. This was entirely novel on the Indian scene”. And quoting Salim Ali, he has added “what are often required for a good field study are a pair of field glasses (binoculars), pencils, paper and patience”.

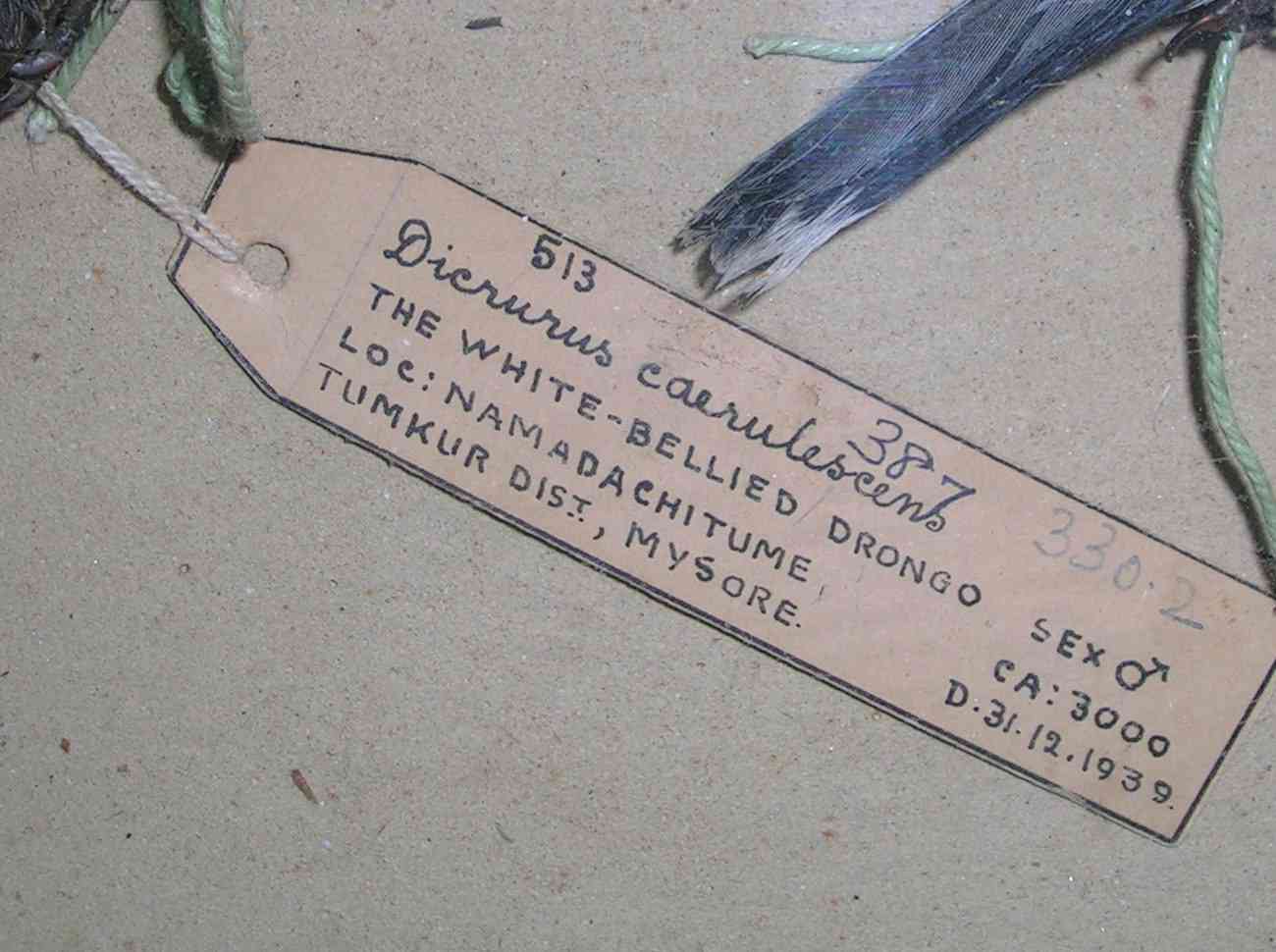

Documenting India birds

At a time when the study of Indian birds was dominated by European ornithologists and the tendency to collect and preserve birds in large numbers prevailed, Salim Ali felt the need for a more live-bird oriented study. Being particularly fascinated by the living bird, he devoted special attention to ecology and behaviour. He was thus able to accumulate a considerable amount of new data on Indian birds, their distribution, habitats and behaviour, in the course of his relentless field work that spanned a few decades. His field observations and notes thus considerably enhanced the available knowledge on Indian birds, especially the book he co-wrote with S Dilon Ripley – Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan.

Salim Ali has described his field documentation method as follows: “… to carry in my shirt pocket a small notebook and a pencil and keep hastily jotting down on the spot. Besides making a list of birds seen, I kept running commentary of any interesting characteristic or unusual observation about them or whatever, in a sort of hieroglyphic shorthand of my own. Back in camp and soon as possible – before the nuances were forgotten – these syncopated notes were ‘decoded’, suitably amplified, and transcribed into a special loose-leaf ledger, each species under its own ‘account head’ in the style of commercial book keeping. Each entry, even when no more than an individual sighting was posted up with its date, locality, altitude, etc., so that in course of time upon opening the ledger at a required page I found spread before me everything I had observed anywhere about that particular species”.

A landmark book

In 1935, when the Bombay Natural History Society commissioned Salim Ali to write a book on the commoner birds of the Indian countryside, the idea of the seminal Book of Indian Birds took shape. By this time, he was rather well-equipped with firsthand field information on Indian birds. And in 1941, the first edition of the most popular book on Indian birds was published. It covered 181 species of common birds with descriptions and coloured illustrations. By the time India was independent the fourth edition was out. More revised and enlarged editions followed and by 1979, the 11th edition was published. The book is currently seen its 14th edition.

Over the years, more than 50,000 copies of the various editions of the book have been sold. But it was the second edition that became the landmark in the history of Indian ornithology and wildlife conservation.

As Salim Ali has put it “in 1942 while in Dehra Dun jail, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru had purchased a copy of the book, got it autographed and sent it to his daughter as her birthday present. The late Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, who about 30 years later set the recent trend in wildlife conservation [Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972] and natural resource management [Project Tiger] in the country, was herself hooked on to birds through this book. And what she later described as a ‘delightful book’ had in fact opened her eyes to an entirely new world, as it had to thousands of other Indians”. Salim Ali has written these lines on Indira Gandhi in his autobiography The Fall of a Sparrow while citing a foreword written by her in 1959 for a book titled Our Birds by Rajeshwar Prasad Narain Sinha.

In 1976, Span carried an article titled Ornithologist Extraordinary written by Salim Ali’s niece Laeeq Futehally. In this article, Salim Ali’s career as an ornithologist has been fairly neatly, though briefly, traced. The year 1930 marked the completion of the six-volume series of the Fauna of British India: Birds by EC Stuart Baker. This work has since been the most relied reference for the taxonomy of Indian birds. Salim Ali had himself heavily relied on this early faunal series.

During the next 20 years, almost all of India, parts of Tibet and Burma (Myanmar) had also been covered through a series of bird expeditions undertaken by Salim Ali. Around 1940, during the World War II he met S Dillon Ripley of the Smithsonian Institution, at Sri Lanka. An association that began with this meeting resulted in the monumental ten-volume Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan. What began in 1953 was finally completed in 1974. None can deny that Salim Ali’s greatest contribution to Indian ornithology is this series of books that cover more than 2000 taxa (species and subspecies) of birds that are found in the Indian subcontinent.

Honours well-deserved

In recognition of his contribution to Indian ornithology and wildlife conservation, the Government of India honoured him with Padma Bhushan in 1958 for “Distinguished Service to Indian Ornithology” and Padma Vibhushan in 1976 for his continued contributions to Indian ornithology. The government also conferred on him in 1982 “National Research Professorship in Ornithology” and in 1983 the “National Award for Wildlife Conservation”. The Indian National Science Academy honoured Salim Ali by awarding him the Sunder Lal Hora Medal in 1970 and the CV Raman Medal in 1979.

Salim Ali, despite his aversion to formal education, had thrust his fingers into academics in India. He successfully helped the Bombay University include ornithology as a post-graduate discipline in the 1960s. His last commitment in 1986 (a year before his death) was attending a seminar on the role of Universities in wildlife research, held at the Aligarh Muslim University between February 24 and 28.

But the wilderness was where he belonged, as his autobiography says: “…As a boy I found it far pleasanter to be chasing birds in pleasant places than doing ridiculous sums in elementary mensuration in the classroom. Since then, I have watched birds through half a century and more, chiefly for the pleasure and elation of the spirit they have afforded. Birdwatching provided the excuse for removing myself to where every prospect pleases – up in the mountains or deep in the jungles away from the noisy rough and tumble of the dubious civilisations of the mechanical high-speed age. A form of escapism may be, but one that hardly needs justification”.

The author is an ecologist with the Care Earth Trust, a Chennai-based biodiversity and conservation organisation.

This article was first published on Mongabay.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting