A young woman in her pajamas stretches and brushes her teeth. The caption reads: “5.30 am – A morning in the life of a 21 year old married girl.”

Then, changed into a blue and white salwar kurta set, she uses a thick paintbrush to apply bright red sindoor on the parting in her hair before adding a red bindi to her forehead.

She heads to the kitchen, where she washes some utensils, then goes to an altar to pray, her head covered with a dupatta. After a quick shot of her enjoying a tea break alone, she is back in the kitchen, the morning sun lighting up her face as she carefully measures pulses to cook for her family.

The video ends with her pouring cereal into a bowl and eating breakfast in a well-lit room – the overlaid text notes that it is still only 9 am. The soundtrack is a Hindi song from 1966 – Zindagi Khwab Hai, with lyrics that insist, “Life is a dream, there’s no distinction between truth or lies in a dream.”

The Instagram reel uploaded by a user named Tanishkka, who has 28,000 followers, has been viewed more than 12 million times. That figure is 4 million more than the total number of views received by the last two reels of the Duchess of Sussex, Meghan Markle, who has four million followers.

Over the past year, Instagram has seen a surge in videos featuring young Indian women with titles such as “a slow morning in life of a 21 year old married girl” and “day in the life of 20 yrs old married girl”. They have been notching up millions of views.

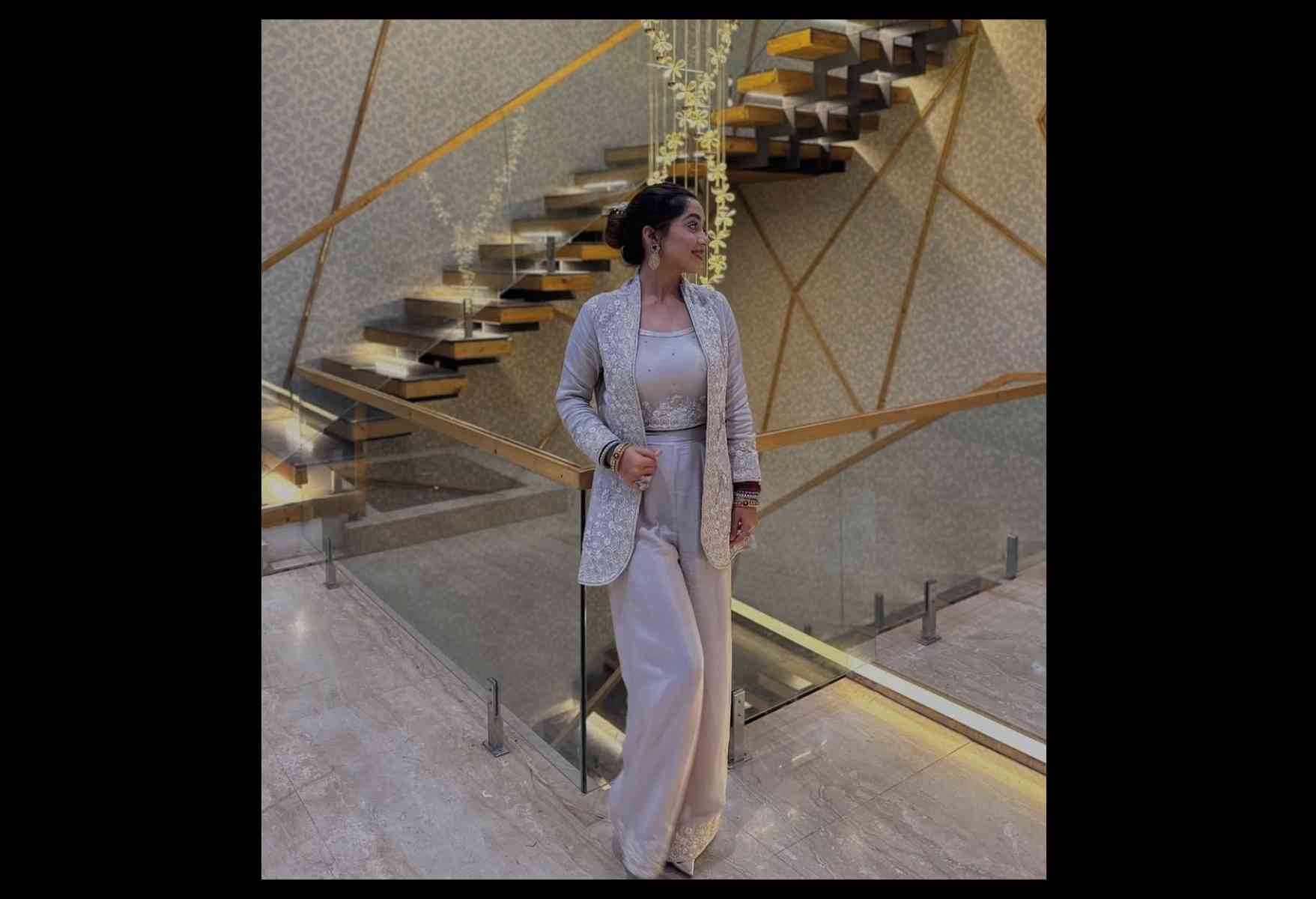

The women in the videos, most of whom refer to themselves as “married girls”, are usually impeccably dressed. Their clothes range from salwar-kurtas to dresses and athleisure wear. They prominently display markers of their marital status, such as sindoor, mangalsutras and red and white bangles up to their elbows.

There is usually an air of comfort and placidity to the videos. The have spacious houses as their backdrops. The women appear content, even blissful, as they pray, cook, wash dishes, chat and drink tea with their families, dress up for outings with their husbands and travel in luxurious SUVs.

But battles rage in the comments sections.

“May this kind of love never find me,” a comment on one such reel. Reads another, “Horror movies don’t scare me, but this reel did, it even appeared on my feed at 3 am [crying emoji].”

Others weigh in to support the creators. “God forbid a woman wants to live a traditional life and be happily married to her husband.” Another comment reads, “This comment section is the biggest proof that women can never see other women be happy! [laughing emoji]”.

Yet another, writing in Hindi, refers to the label by which such creators are sometimes known: “This tradwife trend has started in India too now.”

The term “tradwife”, short for “traditional wife”, has been used since around 2020 by Western anglophone social media to refer to a growing number of women content creators who make videos glorifying marital domesticity, focusing on cooking, homemaking and being good wives.

Usually dressed daintily in a 1950s aesthetic, in clothing such as flared skirts and fitted tops, these “tradwives” expound the virtues of early marriage and motherhood (many have several children), emphasise cooking meals from scratch and endorse the ideal of a wife who is subservient to her husband.

They glorify a return to what they claim are the old, traditional ways that were the norm before Western modernity and feminism pushed women out of their homes to earn a living.

In India, however, the glamorisation of early marriage and domesticity seems paradoxical since this is already the norm: marriage at a young age is widely prevalent and women’s workforce participation has declined over the past two decades.

But these creators seek to project an idealised image of marriage, particularly early marriage. Rather than an oppressive institution, they seem to say it can be modern and “cool”, said a professor of women and gender studies, who asked to be anonymous.

“Their whole thing is that being married doesn’t mean that you go traditional,” she said, pointing out that the creators often wear their red and white bangles with “western” attire like jeans.

“I don’t think that they want to actually claim that they are tradwives at all,” she said. “I think they want to claim that they are ‘mod wives’ – modern wives.”

She said that the trend was disturbing because the creators glorified marriage and domesticity in a society where “most women actually are getting married around the same age” and “do not really have a choice in who they want to marry”.

Like in the West, these Indian creators are endorsing traditional gender roles that largely align with conservative ideologies that are “invested in undermining feminism”, the professor said.

Though the young women seem to be “addressing feminist concerns” and speaking of women’s empowerment, they do so while “undermining the politics of feminism”, she said.

However, creators who Scroll interviewed cited more mundane reasons for producing such reels: shifting to content that focused on their married lives gained them quick attention and followers, they said.

This story is part of Common Ground, our in-depth and investigative reporting project. Sign up here to get the stories in your inbox soon after they are released.

Japneet Sethi, a 22-year-old makeup professional in Delhi, began sporadically creating internet videos after she completed a makeup course following her Class 12 studies.

Her work did not get much attention until one day, after she got married in January, she saw a “day in the life” reel by another young woman. She decided to make one about herself.

She wrote a caption without thinking too hard about it – “22 yrs old married girl”. The response took her by surprise, she told Scroll in a video interview early in July. “It got really viral,” she said. “I gained thousands of followers from that reel.”

In the reel, Sethi describes her day over a video montage of herself preparing meals, chatting with her mother-in-law and going out for dinner with her family.

As her audience grew, she received a range of responses. “I got so much love from people, from strangers who praised me saying that ‘you are doing so well, you are just 22,’” she said. “I got many hate comments as well.”

She said she receives particularly harsh responses to the reels in which she is doing household chores. “I was just making food for my husband or my family, and they judge me saying ‘Had you done something about your career, you wouldn’t be in this position,’” said Sethi. “I was like, have you seen my home? We have five-four maids at our place all the time.”

She added that she continued to work as a makeup artist and posts about taking classes as well. “But people won’t see that,” she said.

Sethi concluded quickly that there would have been no way to please all her viewers. “People in India are very judgmental,” she said. “If I am a housewife, they’re like ‘22 is too young, you should do something in your career,’” But had she worked after getting married, she added, she would be accused of neglecting her husband.

Sethi responded to the comments and criticism in a reel in which she rejects arguments that women at the age of 21are too “immature” to get married. “I am not promoting early marriage,” she said. “I am promoting happy, healthy, post-married life – which people are not promoting.”

She has continued making videos “because people love me so much”, she said.

Like Sethi, Punjab-based Oman Gupta also saw viewer engagement with her posts on Instagram shoot up after she began focussing on her married life.

Gupta had begun to post videos on fashion while in undergraduate college in 2021. Fashion was instinctive to her, she told Scroll in a video interview in early July. She got some brand deals, she recounted, but her posts did not reach a lot of viewers or receive many responses.

This changed after she got married in February. “One day I just wrote this on the heading of my video ‘a day in life of a 20 years old married girl’ and it like fucking blew up,” she said. The next time she posted a reel with the same title, the views climbed to 2 million.

Since then, her Instagram follower count has risen steadily from 8,000 to more than 35,000.

Gupta’s content also plays into dominant caste tropes to attract views. One of her recent reels, in which she refers to herself as a “bania bahu”, has become her most viewed video, clocking more than nine million views. The reel contrasts shots of “expectations”, in which Gupta is seen getting up early, cooking full meals and bowing to her in-laws, with those of “reality”, in which she is seen waking up late, being served tea and taking selfies with her father-in-law.

“I like to show my audience how customs and life differ, because most of my friends are Punjabi like me,” said Gupta. “Writing ‘bania’ and showing their culture gets me reach because people like to watch it.”

Since the engagement on her own account increased, Gupta has also created work in collaboration with lifestyle, fashion and jewellery brands. She says her posts could motivate other young women to create reels and make money.

“Many people get married at an early age – they are forced to,” she said. “Writing my age in the videos can motivate other married people of the same age.”

Like Sethi, Gupta too deals with her share of negative comments. “I don’t know why people get so aggressive,” she said, noting that viewers left comments like “You don’t look like 20.”

Gupta shrugs them off: “Okay, bro. I don’t look 20, but I am 20,” she said.

Gupta is amused by the squabbles in the comments section. “I feel happy that people are out there fighting about who I am,” she said. “I am not bothered. I am just getting rich.”

Gupta was familiar with the tradwife trend and even wondered if she could be categorised as one. “I don’t exactly understand them, but I read some pointers about it,” she said. “And I think I may be one of them.”

She contended that what was most important was that women remained free to choose the kind of life they led. “You want to work, you don’t want to work – that depends on a person’s choice,” she said.

Sethi echoed this view. “It’s up to women,” she said. “This is what feminism is: respecting someone’s choice.” By contrast, she said, most people today “think feminism…means you have to make your career”.

Unlike Sethi and Gupta, 21-year-old Mouni Rajput, another content creator who also posts videos about married life, eloped from her natal home to marry the man she loved.

She recounted that when she told her family about the man she had fallen in love with, they warned her that their customs only allowed arranged marriages. When she attempted to reason with them, they grew violent, she alleged. “They started beating me up, so I left home,” Rajput said.

Not long after, in April 2024, Rajput made a video about her elopement and posted it on Instagram. It received more than 22 million views.

Since then, she has posted reels fairly regularly on themes such as love marriages, being a good wife and motherhood.

While Rajput has earned some money though endorsements, she does not currently strive to monetise her reels, partly because she now has a baby girl to care for. “I am not a creator in the conventional sense – it depends on my mood,” she told Scroll in text messages in Hindi. “Earlier I had a craze for it but now I have responsibilities.”

In some reels, she has expressed contentment with her dependence on her husband’s income. In one, for instance, Rajput shows off her pregnant belly, as overlaid text in Hindi reads, “No tension about my career.” Superimposed over her eyes are digital sunglasses with text that says: “I don’t care.”

As she dances slowly, the text reads, “I am very happy because I have my husband’s love. I even get money to spend for the month on time.”

Then, it asks, “What more does one need?”

This reel received 13.3 million views and more than 3,500 comments, many of them critical.

“What happens when your husband leaves you some day?” asked one commenter. Another said, “Be careful, those people will be coming here soon”, presumably referring to feminist critics. “Her replies to feminists! [fire emoji],” says yet another comment.

Such comments do not faze Rajput. “My husband financially helps me and without struggling that much, I save more than him sitting home,” she said. “In the end, money matters!”

Rajput grew up in a conservative household. “Of three sisters, I am the first who went to college – that too, an open university,” she said. “There was no freedom to do anything, so wanting a career was unthinkable.”

For some time, she had considered looking for a job, but after a “reality check”, decided to drop the idea. “I was not good at my studies and had studied from Hindi medium and my English is weak,” she said. “I have no skills or education, so I would never be able to earn a good salary.”

She added, “And anyway, being a housewife is itself a lot of work. You have to be available 24×7 for your family. It’s a big responsibility.”

Though Rajput evidently endorsed some of the ideas put forward by “tradwife” content, she had not heard of the trend before. “After you mentioned this, I read up on it,” said Rajput. “I think this is a good thing, because everyone cannot be equal.”

Other creators on Instagram have responded with their own videos critiquing these young women for promoting an idealised married and domestic life.

Falguni Vasavada, a marketing professor at MICA, who also posts about women’s issues and has more than 330,000 followers on Instagram, said she was shocked when she first saw this “extremely disturbing trend”.

She responded with a reel on her account, titled “Choice or conditioning”, which received over 1 million views.

Vasavada argues that such women have been “conditioned in their childhood” to favour early marriage and that their assertion that it was their choice is not an informed or educated one. “At 21 years you don’t have maturity, nor do you have exposure to the world outside, and nor are you well educated,” Vasavada says in the reel.

In fact, such content primarily satisfied men, she asserts, because men “love the idea of a woman surrendering to a household at such an early age”.

The popularity of such posts suggests “we are going backwards,” Vasavada told Scroll. But she added that she hopes that such reels are just a “temporary fad”.

Bengaluru-based creator Muskan Madaan is attempting to ensure that it is. When the 24-year-old Madaan, who started creating content in 2021 about career and communication tips, first encountered content by young married women, she did not pay it much heed. But when she began seeing many similar reels she wondered: “What if this is an echo chamber that people never get out of?”

She noticed with dismay the kind of approval the content received from men. They posted comments such as “Queen you dropped this!” and “That’s a real woman!” “That’s not admiration, it’s romanticising obedience and unpaid labour,” Madaan told Scroll.

The phenomenon “scared” her, and so she decided to make a reel in response.

On May 4, Madaan posted a reel parodying the “day in the life of a married 20-year-old girl” trend. In the video, Madaan does all the household chores and cooks for family members – every time she sits down to get her own work done, she has to pause and attend to yet another chore. The reel received more than two lakh views.

The gender studies professor noted that unlike Western “tradwives”, who centre their posts around domestic labour, most Indian creators foreground “conspicuous consumption” by focusing on aspects of their lifestyle, such as makeup, clothes, SUVs, restaurant outings and vacations. “It is responding to the fact that we are on that uptake of the consumption economy,” she said.

Combining the themes of traditional values and a consumerist lifestyle has allowed these creators to monetise their posts. “The life of a housewife is also a commodity,” the professor said. But she added that the content typically elides the immense caste and class privilege that the women enjoy.

PhD candidate and YouTuber Ritika, who goes only by her first name, observed that while the creators show themselves doing “some household chores”, it did not appear that they were “bearing the weight of the entire household on their backs”.

In a 15-minute video where she breaks down the kinds of “tradwife” content made by Indian creators, Ritika observed that class and caste privilege is common to them all. “Who gets to not work and be a trad wife in India is a form of privilege,” she says in the video. “Our history bears testimony to the fact that Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi women have always worked.”

As a consequence, such content erases the “cheap domestic labour” to whom the creators are outsourcing their domestic work, said the professor.

When Scroll spoke to women users of Instagram who watched the kind of content these creators posted, they struggled to articulate why they were drawn to it. “I don’t know why I follow them,” said one.

Another said, “I’ve come across so many Indian tradwives. I have been fascinated by this phenomenon. I find it so intriguing.” Yet another said, “I’ve been wondering what’s up with this sudden surge in tradwife content.”

Academics reasoned that many women saw aspects of themselves in those reels. The gender studies professor noted that the content offered a kind of fantasy for women who shoulder the double burden of domestic responsibilities and formal employment.

“Could my life have been really easy where I didn’t have to work and hustle and take care of the house?” she asked. The reels “seem to suggest that that’s possible”.

But many women choose to work outside the home because they know the “perils of dependency”, she said. That way, “just because their relationship with a man or their natal family fell through, they don’t find themselves destitute on the road in the middle of the night.”

She added, “Those are all of our fears, right?”

Ritika said that the barrage of comments, especially the response from women, perhaps originated from a sense of discomfort. She drew a comparison with the collective anger, stemming from a place of empathy, that women feel during infamous sexual assault cases.

“Remember, back in the day, when the Kolkata and Nirbhaya incidents happened? she asked, referring to the 2024 rape and murder of a trainee doctor in Kolkata and the 2012 Delhi gangrape and murder. “I think it’s just like that. But instead of collective anger, there is this collective fear.”

Similarly, early marriage could also be the fate of any Indian woman, she noted. It was “just a matter of which house” they were born in and how much “money and resources” parents had for their daughters.

“We could have been them and they could have been us,” she said. “I think that is what is very unsettling about all this.”

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting