If you ask Dilliwalas for their memories of Triveni Kala Sangam across its 75 years, the answers may come in every form – aural, visual, gastronomic. Usually, they come all at once: the wiry Manipuri dancers leaping across the amphitheatre, the syncopated beats of the Chhau dhol, the crisp smack of Bharatanatyam feet. Or the mellowness of an aloo paratha, the comfort of shammi kebabs, and even the delicate tinkle of the bell that its canteen manager once wielded to summon waiters.

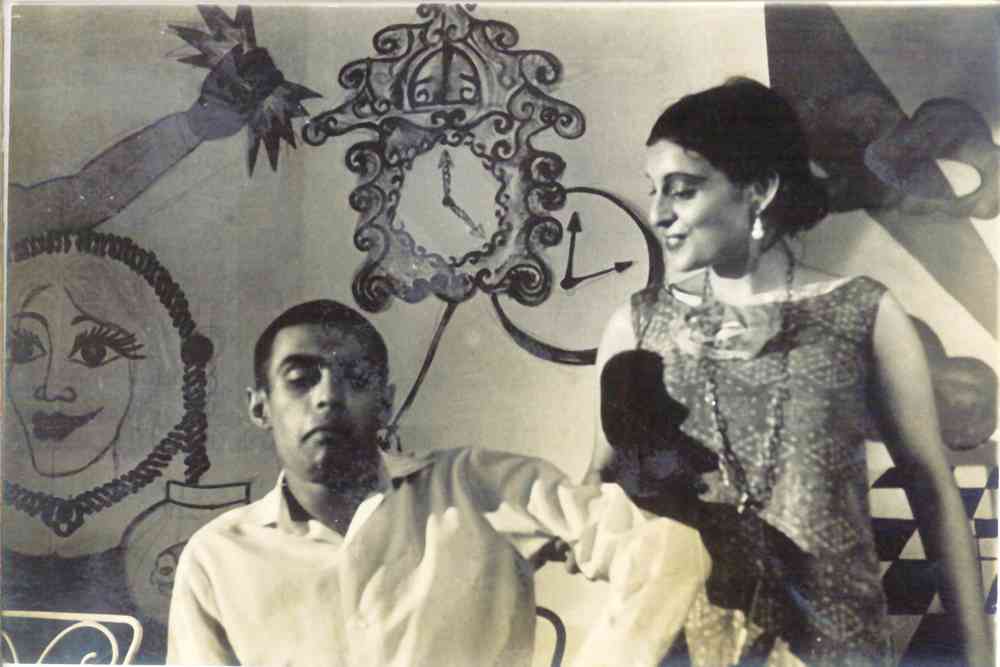

Those sensory imprints persist today, much as they did in the 1960s and 1970s when the legends of dance, music, theatre, art, sculpture and photography taught, performed and created here. Theatre greats Habib Tanvir and Ebrahim Alkazi, dance maestros Kelucharan Mahapatra and Singhajit Singh, and music icons Ravi Shankar and Vijay Raghav Rao all found a home in Triveni’s classrooms, galleries and open-air stages. A fading black-and-white photograph from 1963 shows the jazz pianist Duke Ellington giving a lecture-demonstration in its beloved amphitheatre.

Next February, the institution will celebrate its rich history with these luminaries and other artistes by organising a series of free performances and exhibitions. “It is 75 years of struggles, triumphs and stories of gurus and students,” said Amar Shridharani, general secretary of Triveni Kala Sangam. “We want to build an archive with people’s memories of the place.”

For a multi-arts institution, the unmissable graystone Joseph Stein complex offers a rare sense of welcome and openness with its airy, well-lit design characterised by latticed walls, courtyards and lush green spaces. Nestled along a radial branching off from the bustling Mandi House roundabout, heading towards the foodie haven of Bengali Market, the complex sits in a neighbourhood dense with public and private arts institutions dating back to the 1950s. Yet, here, the gates and doors remain wide open, inviting art lovers and curious wanderers into a world that feels removed from the everyday.

“It has been a phenomenally important cultural centre for Delhi that has had a huge impact on its ordinary citizens because they could, for a small fee, join and learn any art at a time when this was rare,” said noted photographer and curator Ram Rahman. “It brought Bharatanatyam to Delhi in the 1950s, when few had watched the form in the north, and even more importantly, [it brought] Manipuri, of which few knew. Scores of photographers, big and small, learnt under the great OP Sharma and Rameshwar and Shobha Broota trained so many artistes. You could just walk in for a chai and get to watch artistes who you would not otherwise.”

Rahman calls himself a “second-generation” Triveni insider – his architect father, Habib, was a friend and colleague of Stein, and his mother, the great dancer Indrani Rahman, brought Triveni’s first Bharatanatyam guru to Delhi in the 1950s.

None of it, however, would have happened if a ship sailing from London to Karachi had stayed the course.

Humble beginnings

In 1947, a striking young dancer from Karachi was returning home after a stint at a London dance school when Partition riots tore through the subcontinent. Could the liner drop her at Bombay, her worried family pleaded in a telegram. The crew accepted the request, setting her down in the metropolis.

Sundari Bhavnani may have found herself in an unfamiliar city with all of Rs 13 and 11 annas in her pocket, but she was not short on tenacity. She set up a modest home in a small barsati in Borivali and began teaching dance to a handful of students. The next step, almost inevitable in the ferment of post-Independence India, was Delhi. In the capital, cultural institutions like Sangeet Bharati, Kala Kendra and Gandharva Mahavidyalaya were already taking shape in the heart of the new nation. And, besides, Delhi held a personal magnet for her: at a ballet staged at Regal Theatre, she had met her future husband, the dapper columnist, Gandhian and liberal thinker Krishanlal Shridharani.

After moving to Delhi, she briefly took up a teaching position at Lady Irwin College, but soon gave up that security to pursue her dream – to establish an arts institution of her own. Shridharani started small, teaching dance to just a few students. It was a tough time for her. Those who watched her in those years speak of her immense fortitude, of managing with a pair of slippers and a couple of saris that she would wash, iron and wear repeatedly.

Triveni’s beginnings were humble. It opened in 1950 as a teaching centre in a cramped two-room tenement above a coffee house in the outer circle of Connaught Place. It offered Bharatanatyam under Ramaswamy Pillai, Manipuri under Singhajit Singh, flute by Vijay Raghav Rao, and art under KS Kulkarni. Uma Shankar Mishra, a disciple of Ravi Shankar, would soon join as a sitar guru.

“I recall a steep flight of stairs leading to a courtyard that led into the rooms,” recalled seasoned Odissi dancer Kumkum Lal, who had joined Triveni as a schoolgirl, seeking to learn Bharatanatyam under Pillai. “A friend and I would climb the stairs with our legs splayed in a squat to practise the araimandi (half squat) of Bharatnatyam. Guruji, who knew no Hindi, would exhort ‘okkaaru, okkaru (sit, sit)’ because we were not dipping deep enough.”

From its inception, Shridharani infused Triveni with an egalitarian spirit, inspired by her time as a student at Uday Shankar’s dream culture centre in Almora, where she trained alongside Narendra Sharma, Zohra Sehgal, Guru Dutt and Sachin Shankar. It was a vision rooted in accessibility, affordability and independence.

“She was deeply influenced by Almora,” said Kavita Mohindroo, her California-based daughter, a Bharatanatyam dancer and president of the Triveni committee. “The teachers at the centre were artistes very high calibre such as Allaudin Khansaheb, Amubi Singh and Sankaran Namboodiri. So she was clear that the teaching at Triveni had to be impeccable but at the same time available to all, not just the elite. Most classes began free and even today we encourage teachers to help students who cannot afford fees.”

Cultural magnet

At Triveni today, up the stairs from the side of the famed cafeteria – once known simply as Triveni canteen – and onto the corridor overlooking the amphitheatre sits the wooden floored Bharatanatyam classroom. Jayalakshmi Eshwar has been teaching generations of dance aspirants here for the last 50 years.

“Sundariji saw Triveni as an arts centre open to all,” she said. “You could come, watch, stay, leave or move on to what you liked. We used to have parents and children who did not know exactly what they wanted to learn but were welcome to see, maybe take a class or two and decide. She was a strict disciplinarian but she gave us every creative freedom.”

How Shridharani moved Triveni from the dingy two-room tenement in the outer circle of Connaught Place to the contemporary chic of its current Tansen Marg sprawl – and went on become the toast of Delhi’s cultural and social circles – is a story of serendipitous twists and turns, grit, flair, and not a little romance and glamour.

In the 1950s, the Nehru government had begun parcelling out plots for cultural institutions, and most of these had gone to women arts entrepreneurs. The Tansen Marg plot came to Triveni, but an oft-repeated anecdote tells how Shridharani arm-twisted a bureaucrat into parting with additional land. “At our first program…,” Shridharani herself told The New York Times, “the chief administrator of Delhi got up to speak, and the poor man didn’t quite know what to say. So he told the audience that he would give us some land. The next morning, [I] went to see him, and asked him if he was serious, and he said yes. I think both of us were completely taken aback.”

Shridharani requested Habib Rahman to build on the plot for her. But the architect was in the government’s employ, busy constructing New Delhi’s public structures, and he referred her to Stein.

“Stein heard out my mother who wanted it all in a half-acre plot – an amphitheatre, galleries, classrooms, canteen, studios and open spaces – and with all of Rs 10,000 in hand that she made from the classes,” said Amar. “Stein said: ‘Mad.’ But she never gave up. He saw her drive and finally agreed, working for free.” Among her staunchest supporters was Ravi Shankar, who played at the inaugural concert, helped raise funds and collaborated on the hit production Melody and Rhythm.

Five years in the making, the new Triveni quickly became a magnet for artistes, its open-air amphitheatre emerging as the beating heart of the complex. Habib Tanvir’s landmark productions Charandas Chor and Agra Bazar, and Sheila Bhatia’s Punjabi opera Chann Badlan Da, were staged here. Over the years, theatre greats like Sai Paranjape, Amol Palekar and Rajendra Nath brought their productions to its stage, adding to the institution’s growing legend.

Theatre director Feisal Alkazi has fond memories of those vibrant years when Mandi House pulsed with creative frenzy. His father, the theatre great Ibrahim Alkazi, who headed the National School of Drama, founded the Art Heritage gallery at Triveni in 1977. “Dad had come to Delhi after a stint in Mumbai at the Bhulabhai Desai Institute at Breach Candy, a multiple arts hub, so Triveni resonated with him,” Feisal said. “He was also an artiste so he did quite a few shows at its galleries and also a dramatised lecture on TS Elliot’s Wasteland and another on Brecht. So when he left NSD, he set up the Art Heritage gallery at Triveni.”

For Feisal, childhood memories of Triveni are inseparable from its canteen, then run by the formidable Mrs Puran Acharya, bell in hand to summon her staff. “I would be running to my father’s rehearsals from school [Modern School] in my uniform and stop to gobble up shammi kebabs with hot green chutney and two aloo parathas.”

By all accounts, Sundari Shridharani ran Triveni with a firm hand. “She was very strict about cleanliness and propriety, and very pragmatic,” said Rahman. “But it was with the genuine intent of rendering a public service. The other arts entrepreneurs in the area came from rich families but she went through some tough times after her husband passed away very young but she never gave up.”

In her classic sarees and a white blossom stuck behind her bouffant, she never lost any of her fierce, no-nonsense edge till she died in 2012.

Over the decades, Triveni has built relationships anchored in loyalty and shared purpose. Among the oldest of these are its ties with OP Sharma, the acclaimed photographer and teacher, now 88 and ailing, and with Rameshwar Broota, head of the arts department, who first joined in 1957. Broota still comes into work every single day to the second-floor studio of the art department to mentor students and seniors. “I first walked in here when I was 27 fresh out of art college. I remember walking into this inspiring building, the canteen, the students, the artistes and the cosiness and thought to myself: I hope I get to work here someday. As it turned out, I was offered a job here. And I stayed, I am 84 today.” At 8 pm, the lights are still on in his studio, a quiet reminder of Triveni’s enduring spirit.

Malini Nair is a culture writer and senior editor based in New Delhi. She can be reached at writermalini@gmail.com.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting