“Indian dishes… in the highest perfection, and allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequalled to any curries ever made in England.”

— Advert for the Hindoostane Coffee House, ‘The Times’, March 1811.

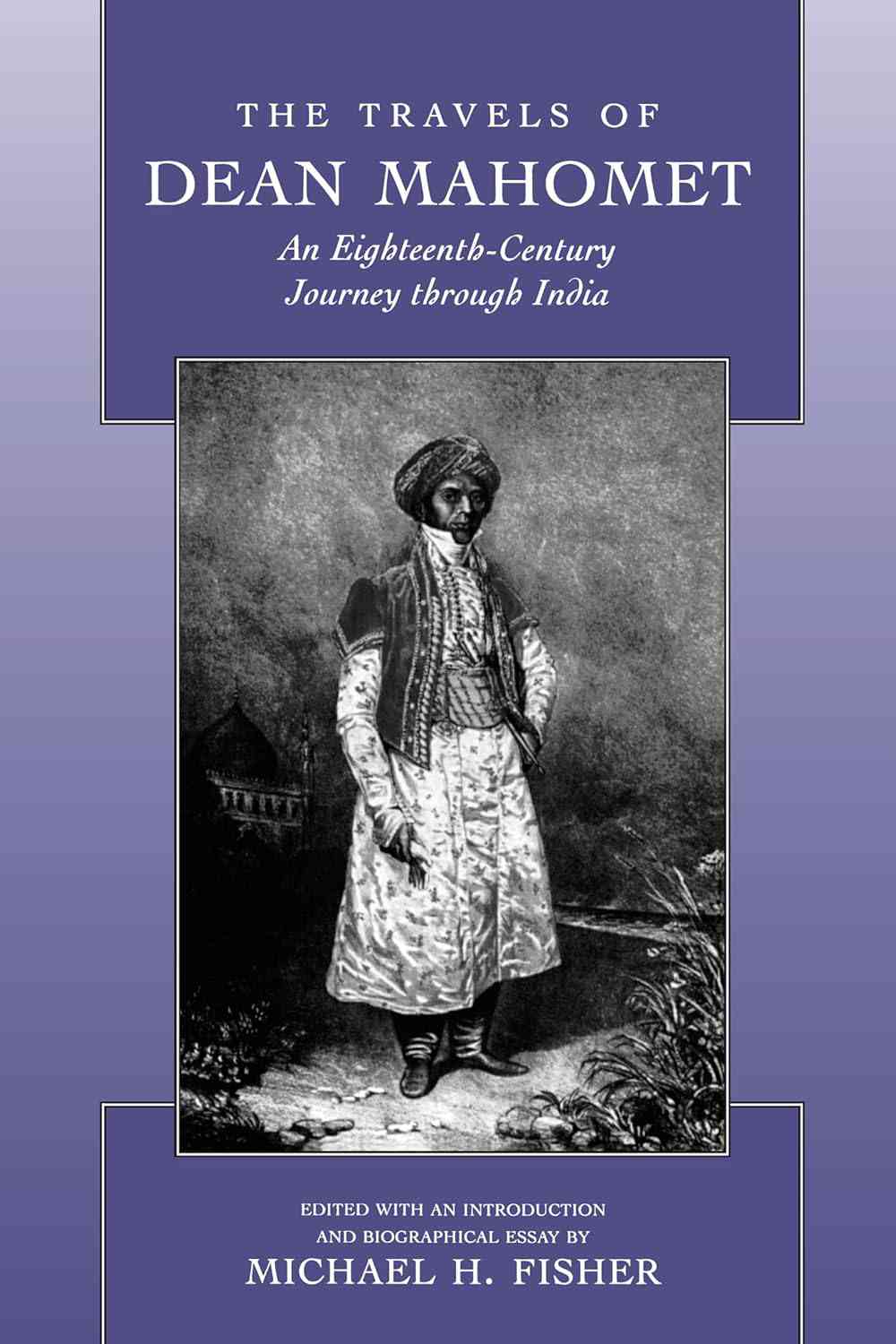

What this advertisement doesn’t mention: the man behind it had already done something far more remarkable. Sixteen years earlier, he’d published one of the first English-language books by an Indian author, funded by 320 subscribers he hustled up himself – self-publishing, essentially, with a dash of crowdsourcing. He composed it in elaborate 18th-century prose he’d taught himself. The book was called The Travels of Dean Mahomet. And it sank without a trace.

I stumbled across Mahomed quite by accident – a footnote about the word “shampoo” led to a spa in Brighton, which led to a restaurant in London, which led to a book published in Cork in 1794. And then the rabbit hole opened.

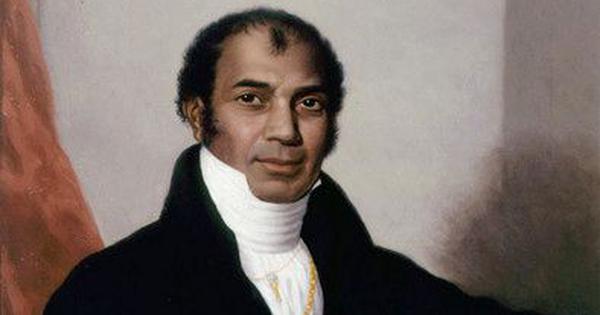

Sake Dean Mahomed, the pioneer

It turns out Sake Dean Mahomed got there first. Before the postcolonial canon. Before Indian writing in English had a name. Before the empire had fully consolidated. He translated himself into the language of the coloniser, and used it to publish a memoir. That alone should have made him famous. It didn’t.

Mahomed was born in 1759 in Patna, just as the Mughal Empire was crumbling and the East India Company was rising. As a teenager, he joined the Company’s army as a camp follower and spent over a decade marching across North India. He later followed his Anglo-Irish officer friend to Ireland, converted to Christianity, married an Irishwoman, and began writing.

The Travels of Dean Mahomet is structured as 38 letters to a fictional “Dear Sir,” describing his life, military experiences, and reflections on Indian society. But this isn’t dry reportage. Mahomed pauses often – to describe cotton weaving in Dhaka, to mull over the etiquette of chewing paan, to describe crocodile-infested rivers, wedding customs, even mangoes. He jokes, explains, and translates.

He also flatters. The book brims with dedications to British officers, respectful nods to the Company, and avoids direct critique. Beneath the surface, however, Mahomed is reshaping how India is seen – not with rebellion, but with redefinition. Where British travelogues exoticised Indian habits, Mahomed contextualised them. Where they found superstition, he found tradition and civility. He borrows from writers like John Henry Grose, but rewrites their judgments. The tone is polite, the subtext sharp.

Crucially, this book was not aimed at Indians or future generations. It was written for a very specific Anglo-Irish elite – educated, curious about the East. Mahomed knew exactly how to appeal to them.

He printed Travels in the duodecimo format – portable, coat-pocket-sized books. He included a glossary. He used elegant, Latinate prose, dedicated the book to a Bengal Army colonel, and listed his 320 subscribers (made up of the Irish elite) in the front, not unlike early cover praise. Each choice whispered: I belong in your world – let me explain mine.

Mahomed speaks with insider confidence. He refers to British officers as “we,” praises Company men, yet quietly restores dignity to Indian spaces, knowledge, and customs. He doesn’t challenge empire outright, but he consistently rewrites its gaze.

Despite the polish and pitch, Travels was ignored. No reviews, no reprints, no literary buzz. It sold to subscribers and disappeared. Under 500 copies were printed.

The reasons are depressingly familiar. Mahomed didn’t fit the template. He wasn’t white. He wasn’t spiritual, tragic, or deferential. He spoke English fluently, placed himself at the centre of his own story, and that made him unreadable – and perhaps even unpalatable – to the audiences of the day.

For 150 years, the book was lost.

Take two

But Mahomed wasn’t done. In 1810, he opened London’s first Indian restaurant, the Hindoostane Coffee House. It promised “Indian dishes … in the highest perfection,” hookahs, and painted views of the subcontinent. But London wasn’t ready, or perhaps not wealthy enough; the venture failed within two years.

So he reinvented himself once more. In 1814, he moved to Brighton and opened an “Indian Medicated Vapour Bath” – the first commercial spa in Britain to offer full-body shampooing (not what we think of as shampoo today, but Indian head massages, or champis). He became known as the “Shampooing Surgeon,” even treating King George IV and William IV, and popularising both the word shampoo and the practice of Indian-style therapeutic massage.

All the while, his first feat – the book – remained lost to history. It wasn’t until the 1990s that Travels was rediscovered and reprinted, thanks to scholars like Michael Fisher. Eventually, it entered postcolonial syllabi and bibliographies of Indian writing in English. The latter is a nod to the fact that this is not just a travel memoir but a sophisticated cultural and historical artefact – part autobiography, part ethnography, part performance, and entirely unique.

The prose is sometimes florid, the pacing meandering – yes. But that is deliberate of its time. What matters is the book’s ambition: to translate a civilisation for another culture, from within, without flinching, pandering, or surrendering agency.

The Travels of Dean Mahomet is a quiet act of resistance – not loud enough to shake the empire, but deliberate enough to survive it.

And survive it did. Long enough to be unearthed again – footnote by footnote, hyperlink by hyperlink.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting