There’s something deeply satisfying about reading old genre fiction, especially the kind that time seems to have quietly swept aside. Between cracked spines, on yellowed pages, or even on the browser tab open to a forgotten PDF, you can find themes and devices that still show up in the latest OTT series, a horror podcast, or a just-published collection. These ancestors, intact and humming, teeming with clues to a past that loved a good story then as much as we do now.

Which is probably why I keep digging: looking for the obscure, the out-of-print, the faintly ridiculous, and the wonderfully eerie. And it’s one thing to unearth an overlooked book – an already exciting prospect, but to find one where even the author is a mystery? That’s a thing of beauty.

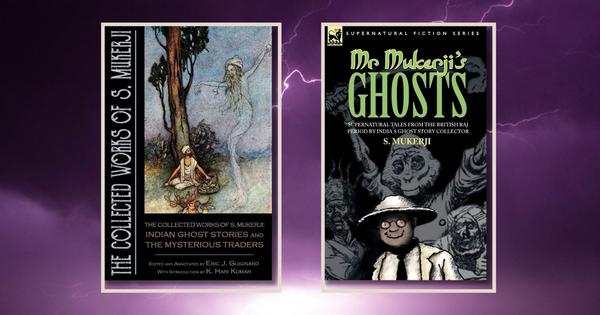

And that’s exactly what makes Mr Mukerji’s Ghosts by S Mukerji so compelling. First published in 1914, the collection is a quietly strange, utterly fascinating window into a world where colonial bureaucracy rubbed shoulders with folk belief. The author, known only as S Mukerji, is a mystery – we can’t turn him into a flesh-and-blood person. There are no photographs, no interviews, no easy biography to lean on. We know he published at least one other work – a serialised detective thriller called The Mysterious Traders – and then more or less vanished. This absence adds to the eeriness: a slim book of spectres left behind by someone who slips through the record like a ghost himself.

Ghosts in India

And the stories themselves? They are from India, not just about it – and that distinction matters, because the context sharpens the pleasure. Ghost stories were, of course, hugely popular in the Raj period, especially among Britons stationed far from home. Rudyard Kipling’s The Phantom Rickshaw and Other Tales and Bithia Mary Croker’s ghost-story collections (modern readers might know Number Ninety and Other Ghost Stories) turned India into a stage for Anglo-Indian hauntings. But Mr Mukerji’s Ghosts, with its twelve supernatural tales, is written by someone who is part of the world they’re set in. This isn’t the outsider’s “mystical East.” This is the everyday India of clerks, judges, professors, soldiers … and the occasional haunting. And they needn’t be translated for an outsider.

In the preface to the book, Mukerji presents himself not so much as an inventor of stories as a collector of cases. He’s careful about sources. He writes, “… in this book, there are a few of those stories only which are true to the best of the author’s knowledge and belief.” And he tells us why some tales just didn’t make the cut for him, his reasoning a product of his time: “A story told by a nurse or a coachman should certainly not be reproduced in this book.” Instead, he privileges accounts from “responsible servants of Government,” including judges and magistrates. It’s an odd, revealing choice. The content is supernatural; the tone is bureaucratic. What we get is the delicious tension of hauntings reported like memos.

On the stories themselves, Mukerji writes a line that’s both modest and mischievous: “I do not know whether writing ghost stories is a mistake.” He notes that many readers prefer tales that end with a rational twist – “towards the end it is found that the ghost was really a cat or a dog or a mischievous boy.” He even cites a then-recent magazine story in which a haunting turns out to be “only a monkey,” calling it “bathos” that goes “too far.” His own preference is different. He wants to leave things as they are – strange, unresolved, a little unsettling. He reminds us that “there are more things in heaven and earth,” and that truth is sometimes stranger than fiction. It’s a small ars poetica for what follows.

The stories themselves are brief, unruffled, and oddly persuasive. The best-known is “His Dead Wife’s Photograph,” in which a group portrait reveals an extra figure: a woman long dead; a bungalow lease keeps changing hands as rumours accumulate – he even includes a floor plan to ground the supernatural in architectural logic, a device now common in horror fiction; elsewhere, a door refuses to stay shut; a child is overtaken by something he brushed against and should not have; a messenger arrives before death does. Mukerji rarely ties a bow on anything. He records, then steps back.

India’s ghost story collector

Reading these tales today, you can feel how they sit at the crossroads of scepticism and belief. The colonial world prized order, lists, reports; the subcontinent’s ghost lore paid no attention to such paperwork. Mukerji stands with a foot in both rooms. He gently mocks the appetite for tidy demystifications while refusing to sensationalise. The result is a register I love for how contemporary it feels: no overcooked atmospherics, no clanking chains; just the cool shiver of the unexplained.

Which brings me back to the mystery of the author. Why so little trace? Part of it may simply be era and circumstance – authors outside the metropolitan circuits often left few footprints. We also know, from the detective serial and from how contemporaries and later publishers referred to him (the 2006 reissue literally names him Mr Mukerji), that he was almost certainly a man. But I like another possibility. Perhaps he didn’t think of himself as an “author” to be known at all. Perhaps he was protecting a day job, or politely sidestepping the whiff of disrepute that the occult sometimes carried in respectable circles. Or perhaps – as his preface suggests – he simply thought of these as curiosities worth putting down, nothing more. The anonymity becomes an aesthetic: you’re left with a voice, a sensibility, and the steady accumulation of uncanny detail.

After its initial publication in 1914 (and at least one further edition in 1917), the book slipped out of sight. In 2006, a small UK press revived it under the title Mr Mukerji’s Ghosts: Supernatural Tales from the British Raj, framing him as “India’s ghost story collector” and leaning into the archival charm. Even then, it remained a quiet rediscovery: a niche curiosity for people who like their hauntings with railway timetables and case notes. But for the horror connoisseurs and literary detectives, the text of Indian Ghost Stories is freely available on Project Gutenberg (from the second edition). There’s also the 2006 Leonaur reissue, Mr Mukerji’s Ghosts: Supernatural Tales from the British Raj, and a comprehensive bookshelf version, The Collected Works of S Mukerji: Indian Ghost Stories and The Mysterious Traders from Dark Moon Books. The latter brings both books by Mukerji into a single volume.

And these books do deserve more readers. In a moment when speculative fiction from the global south is finally getting the attention it should, this little book feels like a missing link. It’s an Indian writer using English to tell from the inside – without apology, without exoticising, without the need to explain away the strange. It blends colonial history, folk belief, and modern scepticism in a way that still feels fresh. It doesn’t shout. It just suggests the world is larger, and stranger, than the reports allow.

Mr Mukerji’s Ghosts may not be the most terrifying book you read this year. But it might be the one that lingers: the after-sensation of a presence, the sense of a story not quite finished, a door that never quite stays closed.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting