On May 19, Sujata Ghadke was wheeled into an operation theatre in Pune, western Maharashtra.

A non-cancerous tumour near her intestine needed surgery.

Doctors at the private hospital had assured her husband, Seelove Ghadke, that it was not an uncommon procedure and Sujata had no other health complications to worry about.

The 4.5 cm tumour was “successfully removed” and a biopsy report confirmed that it was benign.

But as she lay on the hospital bed over the next few days, the 46-year-old homemaker complained of an acute headache and lower body pain. Ghadke flagged her condition to doctors several times, as their teenage daughter Shrushti looked on helplessly. She was given medicines for her pain.

In the early hours of May 25, Sujata fell unconscious.

“That was the last time I spoke with her,” Ghadke, 51, recollects, medical documents spread on his lap and the sofa at his one-storey Pune residence.

In the days that followed, Sujata’s family was told that she had contracted an infection. Doctors put her on antibiotics, conducted a battery of tests, and the hospital bill kept rising.

Ghadke borrowed money from relatives and paid Rs 7.75 lakh. “I earn Rs 25,000 a month at a private firm,” he said. “I don’t have a lot of money saved. But saving my wife was more important. Money I could earn later and return to people,” he said.

But on June 6, Sujata passed away due to septic shock that spurred a multi-organ failure.

A grief-stricken Ghadke, in deep debt and a young daughter to care for, was left stunned. “I kept thinking that her surgery had gone well. It was not a cancerous tumour. Then what went wrong?”

He began to pore over her medical reports.

In Sujata’s blood culture report dated May 26, Ghadke saw mention of “Burkholderia cepacia”.

It was, he found out, a highly resistant rod-shaped bacteria on which at least 10 commonly used antibiotics fail to work.

The doctors had never mentioned how she had got this infection. “Why would they hide it?” he said.

Ghadke began approaching lawyers and trying to track other patients admitted in the same intensive care unit as Sujata to check if they had been infected too.

Over the course of his research, Ghadke came across a medical phrase – healthcare-associated infection, which is also called a hospital-acquired infection or nosocomial infection.

A healthcare-associated infection, or HAI, occurs when a patient gets an infection 48 hours after being admitted to a hospital or within a month of discharge. It is not an infection a patient is originally admitted for.

Sujata’s treating physician, Dr Anjali Pillay, confirmed to Scroll over phone that Sujata caught the Burkholderia infection post surgery. But Pillay refused to comment further, redirecting us to Inamdar hospital, where Sujata was treated.

Scroll sent emails to Inamdar hospital twice – first in July and followed it up in October. We also contacted the hospital management through phone and text messages.

We asked if the hospital had concluded that Sujata’s case was a hospital-acquired infection, if other patients admitted in the ICU with her had contracted similar infections, if the hospital has taken remedial steps after Sujata’s death, and if patients who contract infections get concessions in bills from the hospital. Our emails elicited no response. The story will be updated if and when the hospital responds.

Underreported crisis

Thousands of Indians admitted to hospitals for treatment find themselves saddled with infections that they did not originally have. Not only does this lengthen their hospital stay and increase healthcare costs, for some it even leads to serious medical complications and death.

While there is no official data on hospital-acquired infections in India, several studies have found that the rate of prevalence is amongst the highest globally.

But this remains a massively underreported crisis. Most healthcare-associated infections in India are not traced to source partly because of a lack of awareness among patients. And even when they are, hospitals fail to take responsibility for them.

In this three-part series, Scroll investigates how patients bear the burden of such infections, why they have frustratingly few options of redressal, and how the complete lack of regulation allows hospitals to get away with poor standards of infection control. We spoke to 27 doctors and infection control experts, and filed several Right to Information requests to shine a light on this silent, unacknowledged affliction.

A baby on ventilator

Forty-two-year-old homemaker Barbara Nunes gave birth to a baby girl in November 2020.

As Adrianna had been born premature, she was shifted to the neonatal intensive care unit at a private hospital in Kohima.

In the next three months, Adrianna caught one infection after another – first, meningitis and then pneumonia.

The hospital doctors would tell Nunes that as Adrianna was a pre-term baby, her immune system was weak, making her prone to infections.

But one day in 2020, a specialist doctor from outside was called to examine her. He told Nunes that Adrianna’s vision was impaired.

Till then, she told Scroll, no one in the hospital had told her about this.

Nunes contacted the doctor and met him outside the hospital. The doctor said that he suspected the baby had caught an infection in the hospital which affected her vision.

That is when Nunes decided to dig further.

Over the next two years, Adrianna was in and out of the hospital. But since March 2022, she has been in the hospital on ventilator support due to global cortical atrophy, an infection of the central nervous system that leads to loss of brain cells.

Adrianna, who is fed by a tube, is unlikely to ever recover.

Nunes is convinced that the doctor who had alerted her to a hospital-acquired infection was right.

“Adrianna was in the neonatal ICU on a ventilator, had central line catheters and other devices connected to her, making her extremely vulnerable to infections,” Nunes said.

She claimed that her daughter caught at least 10 different bugs during her stay in hospital.

Over the last couple of years, Nunes has collected laboratory reports that she says prove her charges. Scroll has seen laboratory reports that confirm that Adrianna contracted at least eight infections in the hospital.

“One of the infections she caught developed into meningitis,” Nunes claimed.

But proving that the hospital erred in its infection control protocol has been difficult. “Doctors (from outside) are not willing to testify against the hospital,” Nunes said.

Several doctors told Scroll that confirming a hospital-associated infection is difficult if culture reports of devices or tubes inserted into a patient and instruments used during treatment are missing. Even if such reports are available, a doctor is wary of testifying against another from his fraternity.

Nunes and her husband have decided to fight legally. They filed a civil petition against the multi-specialty hospital in Dimapur. The hospital has filed a counter case in the district court over unpaid bills of Rs 1 crore.

Adrianna remains admitted in the same hospital. Scroll has withheld the hospital’s name since the matter is in the courts.

“Before all this, I did not [even] know what a hospital associated infection was,” Nunes said.

What is a hospital-acquired infection?

A healthcare-associated infection can be of two kinds, explained Dr Rohini Kelkar, an expert in infection control. “It could be due to endogenous or exogenous factors,” she told Scroll.

In the former, microorganisms naturally present within the human body grow uncontrollably. This is how people with low immunity end up with multiple infections during their hospital stay.

In exogenous infections, bugs present in the environment infect the human body.

A hospital is a breeding ground of such bugs.

They can enter the human body through a device, like the urinary catheter or a saline drip, or during a surgery when your body is cut open and infected instruments are used, or when ventilator tubes are pushed down through the nose and mouth. They can also enter the bloodstream through a central line, a tube inserted in the chest, neck or arms.

Kelkar, who has contributed to World Health Organisation’s guidelines on hospital infection control and trained doctors in infection control, said that not all healthcare associated infections are avoidable, especially if they involve patients at higher risk – for instance, cancer patients with extremely poor immunity, senior citizens with multiple co-morbidities, or those on prolonged ventilator support.

But in a majority of cases, “such infections can be prevented by following good infection prevention and control practices”, said Dr Camilla Rodrigues, head of microbiology at PD Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai.

Kelkar agreed: “The hospital can do a lot to prevent most of them by following simple practices like washing hands, and cleaning and sterilising instruments used for surgery.”

How India compares on infection control

Awareness about healthcare-associated infections and their surveillance began in the 1950s and 1960s in the United States and Europe.

One of the earliest records of a critical healthcare-associated infection in India comes from Tata Memorial hospital in Mumbai.

In 1988, three children with leukaemia died at the hospital and five more contracted meningitis within 18 hours of chemotherapy. “When we began to investigate, we found that the likely source of infection was the injection needle used for drawing the drug administered to them. This was likely contaminated,” said Kelkar, who was then the head of the hospital’s microbiology department.

Traces of a pathogen, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, were found on one of the needles. “The hospital immediately switched to single-use disposable needles. We put a whole lot of sterilisation protocols in place after that incident,” Kelkar said.

But to this day, infection control is not a priority for many Indian hospitals, especially nursing homes and smaller hospitals that have limited resources.

“How many hospitals use quality disinfectants? How many follow hand hygiene? How many have state-of-the-art sterilisers? Not many,” Kelkar told Scroll.

The Union health ministry neither maintains records nor mandates hospitals to report such infections.

But the limited studies available indicate that the rates of healthcare associated infection in India is significantly higher than in countries like the US, Europe or Australia.

In the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention records that 3.2% patients get healthcare-associated infections. In Australia, a 2019 study of 19 hospitals found a rate of 9.9% HAI in patients. In Europe, 7.1% patients get HAI, according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

A 2014 study in the Indian Journal of Basic and Applied Medical Research put HAI rates between a wide window of 11% and 83% in Indian hospitals.

In India, the Indian Council of Medical Research is at the helm of the HAI Surveillance Network, which monitors infection rates of 90 public and private hospitals.

Scroll filed a Right to Information request with the ICMR, asking for infection rates recorded by the network.

We sought data on urinary tract infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia and bloodstream infections that are caused by the presence of germs in tubes or central lines inserted in the body – for example, an intravenous catheter used to deliver medicines or fluids to the patient.

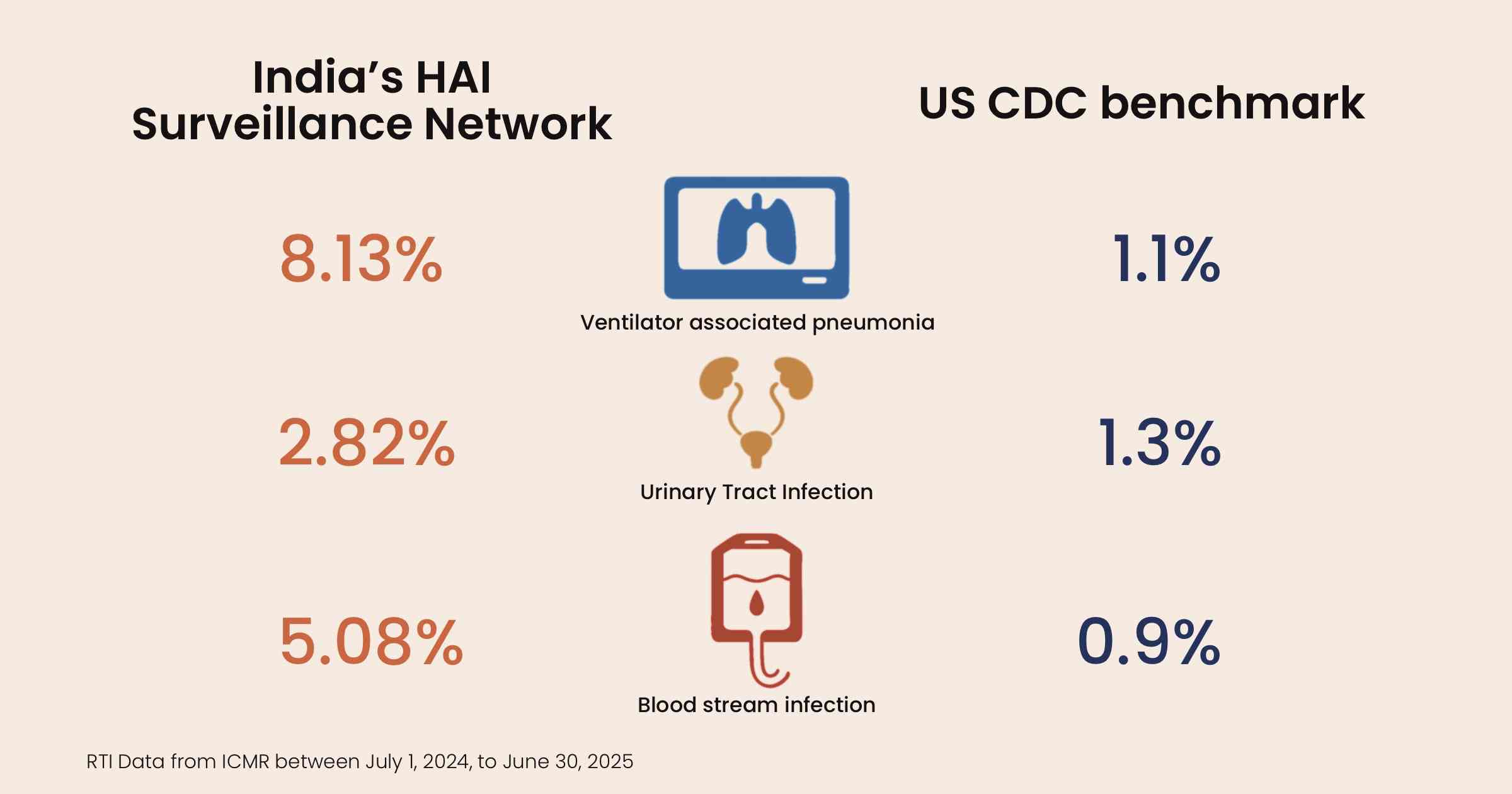

While ICMR said it did not have data on individual hospitals, its response showed that overall infection rates were far higher than the benchmark set by the US’s Centers for Disease Control.

For instance, between July 2024 and June 2025, bloodstream infections in the 90 hospitals that were part of the ICMR network was at 5.08 per 1,000 line days.

This figure was derived by dividing the number of patients with bloodstream infections by the total number of days for which any central line is inserted on all patients and multiplying this by 1,000.

Similarly, urinary tract infections, which is an infection in the bladder, urethra or kidneys due to germs that enter through urinary catheter, were at 2.82 per 1,000 line days, and the rate of ventilator associated pneumonia – lung infection caused by ventilators – was at 8.13 per 1,000 ventilator days.

The benchmark set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for bloodstream infection is 0.9 per 1,000 line days, urinary tract infection is 1.3 per 1,000 line days and ventilator associated pneumonia is 1.1 per 1,000 ventilator days.

Some argue that the CDC’s standards are hard to meet for a developing economy like India.

A more rational benchmark has been set by International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium for low and middle-income countries: 4.9 per 1,000 line days for bloodstream infection, 5.3 per 1,000 line days for urinary tract infection and 13.1 per 1,000 ventilator days for ventilator associated pneumonia. Even here, Indian hospitals fail to meet the benchmark for bloodstream infections.

A more recent study in the Lancet looked at infections in blood specifically caused by central lines in 54 Indian hospitals over seven years. It found the rate of infection to be 8.8 per 1,000 device days, 10 times higher than the figure in ICUs of the USA, at 0.87 per 1,000 device days.

Longer hospital stays, patients unaware

Most Indian hospitals are unwilling to reveal information about suspected healthcare-acquired infections to patients’ families, nor do they take financial responsibility for lapses in infection control practices. As a result, families have few ways to seek redressal.

For instance, in Sujata’s case, the bacteria found in her reports – Burkholderia cepacia – is mostly known to spread through contaminated instruments or use of non-sterile water.

But since the hospital did not divulge information to Ghadke or respond to Scroll, the route of infection in her case is difficult to ascertain.

When Scroll showed Sujata’s reports to an independent infection control expert, she said it was difficult to ascertain the route of infection since the hospital never sent the instruments used on Sujata and tubes inserted in her body for tests to look for pathogens. If they did, the reports were not shared with Ghadke.

In many cases, patients do not even come to know that an infection they acquired in a hospital has resulted in a prolonged stay and increased their hospital bills.

A study from Bhopal’s AIIMS found that such infections led to an increased ICU stay – 13.8 days on an average – compared to 8.2 days amongst patients who do not acquire such an infection. In private hospitals, the stay is longer.

“A longer stay means that the cost of treatment also increases,” Santenna Chenchula, the study’s lead author, told Scroll.

In a government hospital, that could mean an additional cost of Rs 35,000 to Rs 85,000, and in a private hospital about Rs 2 lakh more, according to various studies of HAI treatment in India that Scroll assessed.

But Scroll found that in reality patients had to shell out much more in private hospitals.

For Sujata, the treatment that began with a simple tumour removal surgery costing Rs 1.69 lakh and scheduled hospital stay of six days rose by seven times to Rs 11.5 lakh in 20 days. Till date, Ghadke has not cleared the entire bill.

The fight for compensation

For a patient who has contracted a hospital acquired infection, there are few remedies. There is no law to govern such cases in India. They cannot approach medical councils.

Dr Shivkumar Utture, national chairman of Indian Medical Association, and former member of the Maharashtra Medical Council, said, “Medical councils only look at cases of negligence against a doctor, not an entire hospital. A healthcare-associated infection involves a hospital, not a doctor. It falls outside our purview.”

In some cases, patients’ families have approached state medical councils and been turned down. The police are also wary of registering first information reports unless a government hospital or a district civil surgeon confirms a hospital-acquired infection in writing.

Raghvendra Rao, a patient rights activist, said the biggest challenge is to get another doctor to certify that the infection is hospital acquired. “It is a conspiracy of silence,” Rao said. “Seldom do doctors agree to certify against members of their own fraternity.”

“There are very few cases where patients succeed in getting compensation,” said Amulya Nidhi, an activist with Jan Arogya Abhiyaan, an umbrella association of not-for-profit health organisations.

One route is approaching the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission. “Even they usually ask for an outside doctor’s report,” Nidhi said.

Aalim Javeri, now 33, was 10 years old when his father, Sadruddin Hashimali Javeri, died of septicaemia in a private corporate hospital in Hyderabad following a bypass surgery conducted to clear blockages in his artery.

Through his medical documents, the family realised that 64-year-old Javeri, who was an advisor to the scion of Hyderabad’s former royal Nizam family, Mukarram Jah, had contracted multiple infections during his post-operative care.

Laboratory test records at the hospital showed that the tip of the catheter inserted in Javeri, had Staphylococcus sciuri, a gram positive bacteria that is resistant to a wide range of drugs.

Another report found that the fluids in the endotracheal tube, which is inserted in the throat of ventilated patients, had gram positive bacteria. A third tube called intercostal drainage tube, which is used to extract fluids from around the lungs, had Staphylococcus bacteria growing on it.

“The hospital staff did not change the catheter frequently,” Aalim said. “The post-operative care was shambolic.”

The insurance company refused to clear the claim because the hospital did not provide original bills, Aalim claimed.

It took three years, during which the family collected evidence, contacted experts, and finally approached the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission in 2005 to seek compensation from Care hospital in Banjara Hills, a part of the Quality Care India Limited.

During the hearing in the commission, the hospital maintained that it “took all necessary precautions and administered appropriate antibiotics based on culture sensitivity reports” and that the patient had a medical history that made him susceptible to infections. The hospital did not respond to Scroll’s email.

It took 19 years for the commission to pass an order identifying the hospital’s negligence and asking it to pay a compensation of Rs 10 lakh to the Javeri family.

The hospital has appealed the decision at the Supreme Court. Javeri, too, has approached the apex court stating that the compensation is not adequate.

Javeri’s mother, Begum Scheherazade Javeri, passed away in March this year. “She didn’t get to see justice delivered,” Aalim said, recounting the innumerable visits they had made to Delhi for hearings, and the adjournments that delayed the case for two decades.

“If this can happen to us,” Aalim told Scroll, referring to the influence the family has due to its closeness to the Nizam’s descendants, “imagine what could happen to others?”

This reporting was supported by a grant from the Thakur Family Foundation. Thakur Family Foundation has not exercised any editorial control over the contents of this article.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting