In April 1859, an advertisement in the Bengali journal Tattwabodhini announced that prints of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar’s portrait had been released for sale. The insertion read:

People across the land have heard of the good deeds of our most venerable benefactor, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, but most have not had the opportunity to see him. For those wishing to do so, we have made copies of his portrait available. Each print measures about one-and-a-half arms’ length [approximately 27 inches] and is priced at 1 rupee. They can be obtained by sending the abovementioned amount to our [NC Ghosh Company] offices on 23 Lal Bazar.

At the time, Vidyasagar was not yet forty but his fame had evidently spread wide enough that there was a demand for his image. Born Ishwar Chandra Bandyopadhyay in 1820 in Birsingha in present-day West Midnapore, the champion of widow remarriage had already borne his “Vidyasagar” epithet for two decades. He had completed his education at the Sanskrit College, cleared the law examination and taught for several years at the Fort William College by this time – apart from leading a successful campaign that contributed to the passing of the Hindu Widow Remarriage Act of 1856. Just below the insertion in Tattwabodhini, appears another advertisement, this time for a portrait of Raja Ram Mohun Roy (1772–1833).

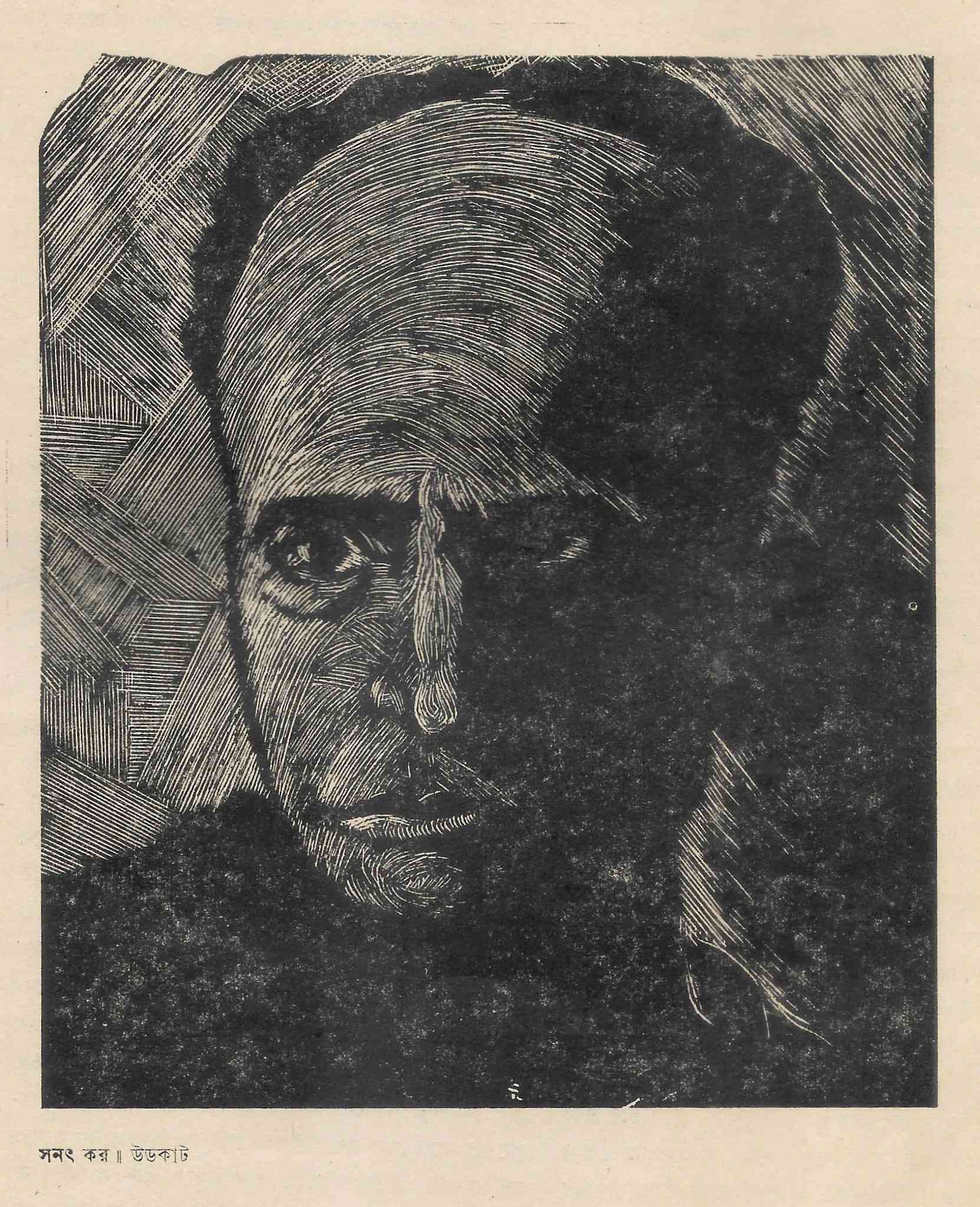

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820–1891), one of the most recognisable faces of the (contested) “Bengal Renaissance,” was a controversial figure even in his lifetime. As one of his most sensitive biographers, Brian Hatcher, writes, his legacy in the popular imagination has been reductively defined by “hagiographic labels” – “an ocean of learning (vidyasagar) … an ocean of compassion (karuna-sagar) and generosity (dana-sagar), a friend of the weak (abala-bandhu) and the poor (dina-bandhu)”. My intention here, however, is not to assess Vidyasagar or his legacy on his 205th birth anniversary, but to reflect on his images – made during his life and posthumously, although not exhaustively – through one particular portrait drawn by painter and sculptor Ramkinkar Baij (1906–1980).

Picturing the Ocean of Learning

In his lifetime, Vidyasagar witnessed pivotal developments in the history of image-making, including advances in print technology, the emergence of academic realism in South Asian art, the rise of photography, and a growing enthusiasm for civic statuary. The new “public sphere” was, after all, as visual as it was textual.

As the advertisement in Tattwabodhini signals, Vidyasagar’s portrait had begun to circulate in print by 1860. A few years later, Benjamin Hudson (1823–1891), who had arrived in India in 1854 and found patronage with the Paikpara Rajas, painted a portrait of Vidyasagar. Hudson refused to accept remuneration for his efforts. Out of gratitude, Vidyasagar commissioned portraits of his parents, Thakurdas Bandyopadhyay and Bhagabati Devi, who were on the verge of leaving their native home in Birsingha to retire in Benares.

It was unusual for women from traditional households to appear before a foreign, male artist, so Bhagabati Devi was understandably reluctant at first. “What will I do with a portrait?” she said. “Shame, shame!” Ishwar Chandra replied, “The portrait isn’t for you – it is for me. I will carry the two with me wherever I go.” They came around to it eventually and had to travel to Paikpara a few times before Hudson completed his work. Since then, these portraits, along with Vidyasagar’s own, have been reproduced in numerous biographies.

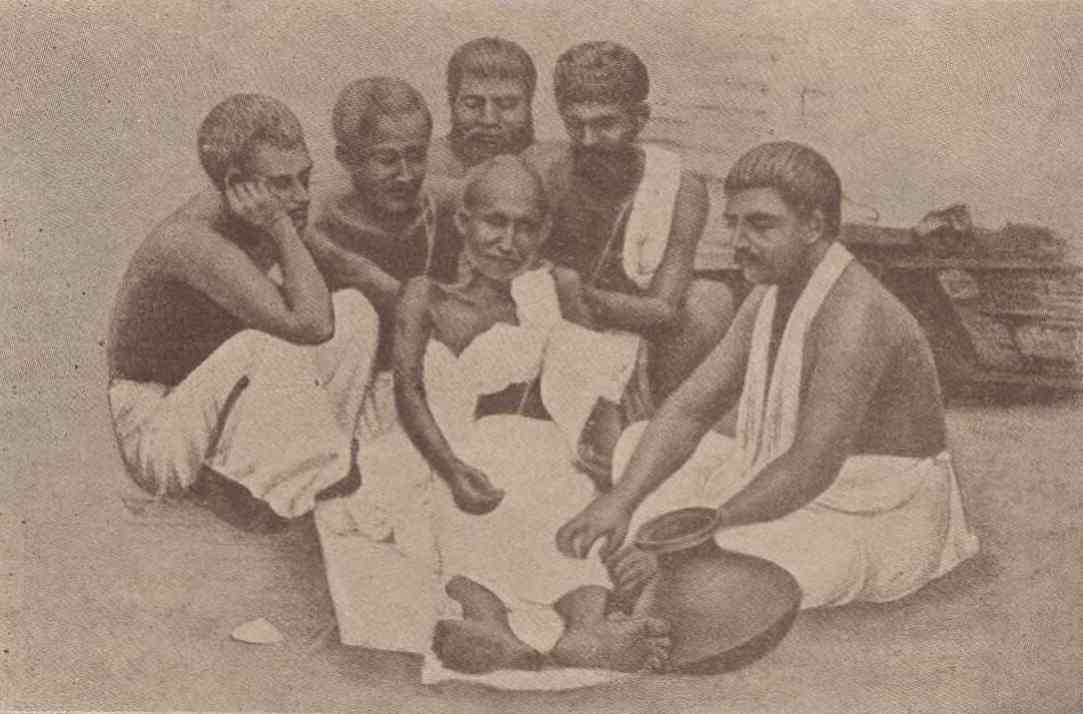

When it comes to photographs, a rather grim tale surrounds Vidyasagar’s passing in 1891. His biographer Behari Lal Sarkar recounts that his brothers were eager to proceed with the last rites soon after he died late at night. His grandsons, however, insisted on having a photograph taken, delaying the cremation at Nimtala Ghat until daylight. A photographer by the name of Sarat Chandra Sen was summoned for the post-mortem photograph. (The practice was not uncommon at the time, as historian of technology and science-fiction writer Siddhartha Ghosh notes).

Lithographic reproductions of the photograph, prepared by Annadaprasad Bagchi, soon appeared in multiple publications. Sen, who had recently relocated to Calcutta, would later remark – apparently without irony – that the three images he made of Vidyasagar more than compensated for the losses from his business venture in Delhi: “What I want to say from the bottom of my heart is this: Vidyasagar helped many a soul during his lifetime, but even in his death he became my benefactor.” Ghosh suggests that Vidyasagar’s most famous seated portrait was also probably made by Sen, whose kitsch “variants” continue to circulate in popular print even today.

The first statue of Vidyasagar was installed eight years after his death, as Kamal Sarkar noted in his Kolkatar Statue (1990). The seated marble figure, created by Durga Mistry, was placed in the quadrangle of Sanskrit College, Calcutta, replacing a statue of the Scottish educationist and watchmaker David Hare. On the same occasion, Phanibhushan Sen of the Calcutta Art Studio produced an oil portrait of Vidyasagar. Mistry’s statue was later relocated to College Square, while another seated figure – this one by the Italian sculptor Ermenegildo Bois, who had secured patronage under Jatindramohan Tagore – was installed at Sanskrit College.

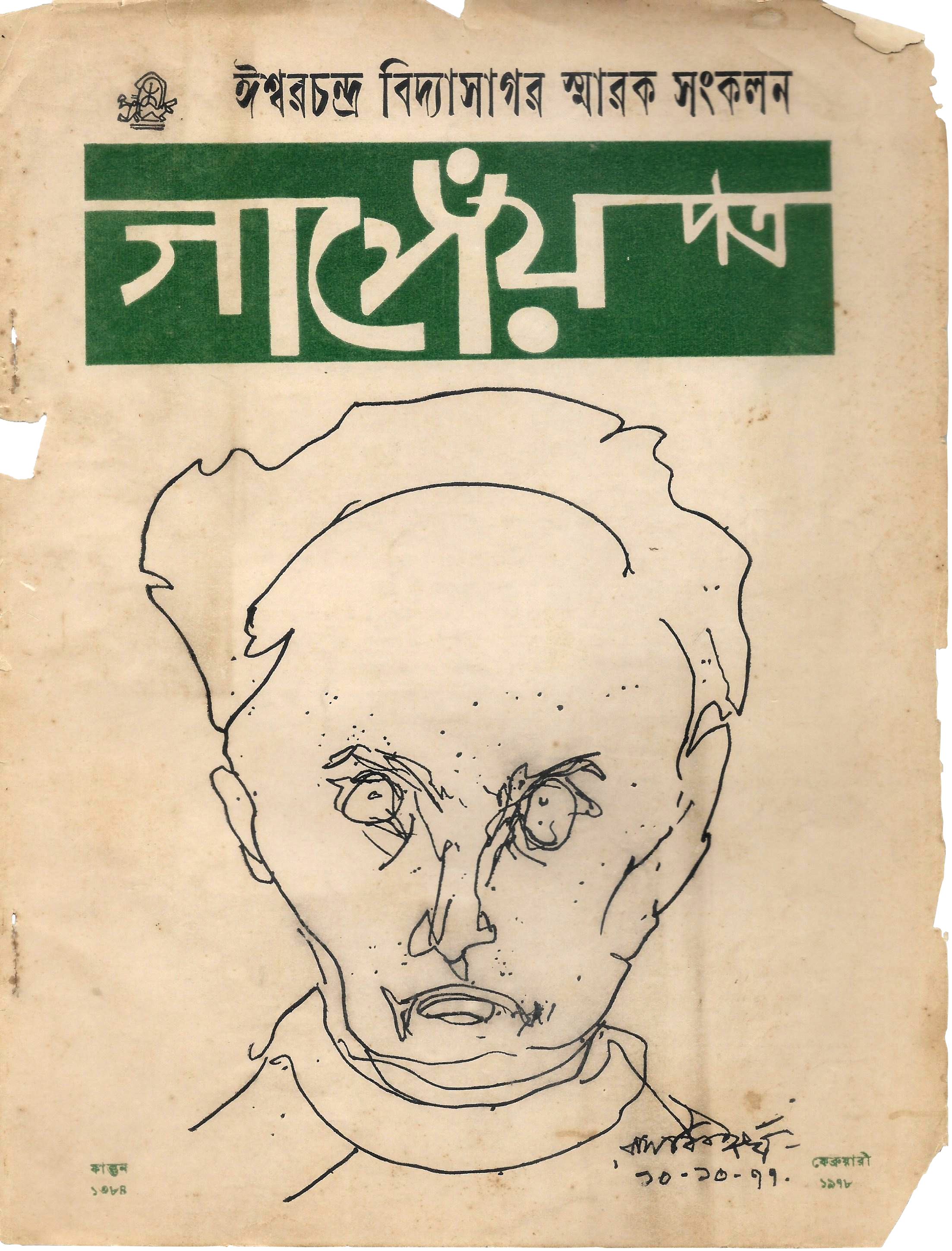

These and other statues of Vidyasagar came under attack in the 1970s, as the Naxal movement ushered in a radical reevaluation of the “Bengal Renaissance,” expressed, in part, through acts of iconoclasm. The seated Vidyasagar in College Square was damaged twice – first in 1970, then again in 1978. The Bois sculpture was also attacked, after which it was replaced by another seated figure by Pramod Gopal Chattopadhyay. It was in this conflict-ridden climate that a Bengali little magazine called Gangeo Patra, with a circulation of no more than 500, decided to publish a special issue on Vidyasagar – and, for its cover, solicited a portrait from Ramkinkar Baij. (There was a more recent incident of statue-smashing as well, which Brian Hatcher mentions in his 2019 article on Scroll.)

Ramkinkar’s Vidyasagar

Gangeo Patra had begun its journey in 1975. Edited and published by Anjan Sen and Uday Narayan Singha, it featured poetry, and essays on art, literature, linguistics, sociology, and critical theory, accompanied by illustrations and reproductions of paintings by artists such as Ganesh Pyne, Shyamal Dutta Ray, and Nirode Mazumdar. By 1978, it had secured a steady readership, who found in its pages an editorial approach that sought to de-centre the Anglo-American hegemony over academic theory. The Vidyasagar special issue (Phalgun 1384/February 1978) offered a wide range of writings: a few previously published essays, lecture transcripts and poems, as well as several articles reflecting on his contested legacy. A selection of poems by familiar names such as Dinabandhu Mitra, Shakti Chattopadhyay, Amiya Chakrabarti and Anukana Khastgir, was accompanied by adulatory songs of the taant weavers of Shantipur (anonymous, unfortunately).

When Anjan Sen showed me the issue, however, I couldn’t tear my eyes away from its haunting cover. Overpowering the Gangeo Patra masthead designed by Shyamal Dutta Ray, was Vidyasagar’s face – stark, formidable, even accusatory. It is unlike any portrait of Vidyasagar I had seen or even dared to imagine. He does not have the usual far-away, philosophical look but confronts the reader directly. “How did you get Ramkinkar to draw this?” I asked Sen.

“I caught a train and reached Bolpur,” he began. “Sanat Kar [painter and print-maker] had already mentioned my plan to Ramkinkar. He agreed readily to my request, but before he began, Ramkinkar wanted a copy of Barna Parichay [Vidyasagar’s iconic Bangla primer]. I went all the way to the station, bought a copy, whose cover featured the author’s portrait, and brought it back. Ramkinkar stared at it for a while. Then he took a sheaf of pages and began drawing portrait after portrait with his pen. He would make one, grunt in disapproval, and toss it aside. I couldn’t resist reaching for one or two of the rejects, but I was told to sit still. Eventually, he produced one to his satisfaction. That was the image we turned into a block and used for the cover.”

What passed through the artist’s mind and heart as he sat down to confront Vidyasagar, I wondered. Writing about Ramkinkar Baij’s portraits – he made many over the years – art historian R Siva Kumar observes, “How he construed each portrait or image of a person depended on his relationship with the individual.” Siva Kumar recalls a 1935 sculpture of Ustad Allauddin Khan, where Ramkinkar had been forced to work off short single sittings, before “completing it from memory.” His evocative portrait of Abanindranath Tagore was also done from “three sittings of fifteen minutes each” – marking “a personal method that allowed him to free himself from strict adherence to the physiognomy of the subject and interpret the personality more freely.”

Occasionally, Ramkinkar would return to the same face over and over. With Rabindranath Tagore, for example, he would allow himself room for freer play of the imagination – perhaps reflecting the spirit of the poet himself. In his famous portraits of “Swapnamoyee” and Binodini (poet, painter, princess of Manipur), however, Ramkinkar’s models “do not lend themselves to be unilaterally seized by the artist.” His gaze, Siva Kumar writes, is met by their counter-gaze, transforming the portraits into moments of encounter between artist and subject.

It is telling that for Vidyasagar, Ramkinkar Baij relied on a reference image – one that had almost become a visual cliché. Unlike Allauddin, Abanindranath, Rabindranath, or Binodini, here he was encountering a figure separated from him by a considerable temporal distance. Was it still possible to imagine a personal relationship? For Ramkinkar, Vidyasagar was probably most significant as the champion of Bangla letters. In a later interview with Anjan Sen, he would express his displeasure with the statue-smashing of “the man who gave us literacy.”

The artist, whose relationship with the subject defines the image, was keenly aware of how his historical position shaped his own subjective position. The portrait he drew, then, was not just of Vidyasagar, the icon in his time, but of a man who had been made to stand public trial by history and historiography even after his death. Ramkinkar chisels away the “hagiographic labels” to present before us a human being, difficult even with those close to him, in his most unaccommodated form. Vidyasagar looks out from the page, daring us to meet his gaze; his portrait thus disrupts that safe boundary, which allows the living to judge the dead. The original pen-and-ink drawing, returned to the artist after printing, has not, unfortunately, been traced yet.

The author thanks Anjan Sen, Sarbajit Mitra, Mita and Sondwip Mukherjee for their help with sources.

Sujaan Mukherjee enjoys researching and writing on art, literature and cities. He completed his PhD as a SYLFF fellow from the Department of English, Jadavpur University, and a postdoc at the CSSSC as a Mellon Foundation fellow. A two-time IFA awardee, he has worked with several archives and museums, including DAG’s museums initiative, Victoria Memorial Hall, SCTR (JU), JBMRC (CSSSC), and Gurusaday Museum. He is currently Senior Curator at the Birla Academy of Art and Culture, Kolkata.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting