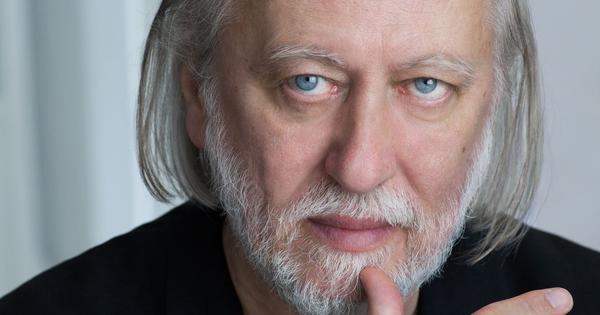

Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai was published by the journal Almost Island in 2008 and 2013. He was a guest at the Almost Island Dialogues held in 2013, in New Delhi, where he delivered a talk and a reading from his work. Sharmistha Mohanty, founder-editor of Almost Island, interviewed Krasznahorkai in Budapest in 2012, and had several conversations with him in New Delhi afterwards.

László Krasznahorkai has won the 2025 Nobel Prize for Literature. He has been called a master of the apocalypse, of dystopia and devastation. His work refracts not only the darkness of a brutal, desperate world, as seen in the small towns and rural areas of Hungary, but also the few attempts at transcendence that this world holds. His first work was Satantango, a moving and disturbing portrayal of a desolate village moving towards its destruction. Over the years, he has travelled from the dystopian to looking at a complex, nuanced beauty in books like Seiobo There Below, and the meditative and serene A Mountain to the North, A Lake to the South, Paths to the West, A River to the East.

Krasznahorkai stands with the great innovators of literature who opened up and changed the course of the novel, taking it away from traditional realism towards individual directions and worlds. He stands with Franz Kafka and James Joyce, with Marcel Proust and Hermann Broch. Just as none of these writers resembles each other, Krasznahorkai too is like no one else. His only similarity with the others is in widening, unforgettably, the realm of the possible.

The infinite world of consciousness

And what takes us into the heart of his universe is his utterly singular language, his legendary long, serpentine sentences, that continue over many pages, sometimes almost building up to an incantation. And in fact, they have the gravity of a chant, these sentences with a heft that never sinks. In Krasznahorkai’s work, the infinite world of consciousness cannot be tamed into plot or paragraphs. As he himself says, he “wants to give a total picture about the earth.” His books demand an almost unprecedented attention.

“Everything here is ours again, it’s ours again because we have won back power over the earth, and nothing remains after the battle, we devoured everything, we killed everything, we destroyed everything, just the bare earth that’s all there is now, no flowers at all, not even one blade of grass remained, no fields or meadows or forests or oceans or seas, or gulfs or continents at all, only a thick, dead ash upon everything that was; there shall be no mountains, no more rivers, nothing shall ever rise towards anything else, and nothing shall flow anywhere any more…”

— From ‘Animalinside’

In an essay on German writer Hermann Broch written in 1949, the philosopher Hannah Arendt has said, “The novels of Proust, Joyce and Broch…show a conspicuous and curious affinity with poetry on the one hand and philosophy on the other. Consequently, the greatest modern novelists have begun to share the poets’ and philosophers’ confinement to a relatively small, select circle of readers. In this respect, the tiny editions of the greatest works and huge editions of good, second-rate books are equally significant. A gift for storytelling which, half a century ago, could be found only among the great, is today frequently the common equipment of good but essentially mediocre writers. Good second-rate production, which is as far removed from kitsch as it is from great art, satisfies fully the demands of an educated and art-loving public and has more effectively estranged the great masters from their audience than the much-feared mass culture.”

Krasznahorkai is that poet and philosopher of whom Arendt speaks, one of the few today who have had the courage to be himself and survive.

Krasznahorkai says he never really wanted to be a writer. It is 2012, and we are sitting on the banks of the Danube in Budapest. He sits with his back to the large windows overlooking the river and I sit facing them. As the conversation goes on, I see the afternoon light changing over the river and slowly falling, losing its gold and turning into evening.

Krasznahorkai is from Gyula, a small town far from Budapest, a town which he left when he was very young. He says he wanted to go far from his bourgeois family. He lived and worked in other small towns, with the poor, and his jobs included being a miner and a night watchman for three hundred cows. “That was my favourite – a byre in no man’s land. There was no village, no city, no town nearby.”

He was also the director of the cultural houses that were common at the time, under Soviet rule. The cultural houses had libraries where people had some access to books. There were six of them under him, so he would travel between these villages. It was this experience that impelled him to write his first novel, Satantango. He never really thought he would write another book. “I never was attracted by the culture of the centre, of Budapest.”

“But when I read Satantango again later, I realised that the book was a mistake. So I wrote another book, hoping that it would be without mistakes, The Melancholy of Resistance. And so it happened with each book. When I began, in the first novel, I felt I knew something. Now, in my last years, I feel I know nothing…But writing shows me…it makes a territory with words where we can live a spiritual life.”

In his work, there is often an intellectual in the midst of a small town of humble, often devastated people. Krasznahorkai is equally present, as a writer, in both. I ask him about this. He says, “They taught me everything I can see now. But only together. The thinkers, and the devastated people…and the intellectuals are only intellectuals from the point of view of society. In reality, they are people alone in the universe. But they have much more ability than others to articulate their situation.”

He says, “Perhaps the problem of the intellectual or even the artist is this. We feel we have to show the world something – but really, we have another task. To sit quietly by a river and hear its sound, look at its surface, to see the light move on the water. This is more important than the great and little judgments of the world…”

Dark and light

Krasznahorkai’s world is very large. From a small Hungarian town his life takes him to Mongolia, then China and Japan. He spends years in the Far East, in Japan living with a master of the Noh. He travels also to the United States, living for a while in the apartment of Allan Ginsberg in New York.

One of Krasznahorkai’s more recent works is Seiobo There Below, a collection of encounters with some of the world’s greatest artistic achievements, like the Alhambra, or a Buddhist monastery, or the Venus de Milo, all rendered in a lightly wielded fictional voice. Writing of the great Noh master Ze’ami, he writes, “He had not created a theatre because the Noh is not a theater, but a higher if not the very highest form of existence, when an individual, by dint of a cultivated sensibility, unique intuition and genial introspection, the competence of a profound engagement with a tradition of the highest order, creates revolutionary forms, never before experienced, and in doing so elevates all human existence…”

Krasznahorkai has worked and lived with people who have the hardest and most brutal lives. He has moved from writing novels about these lives and worlds to a work on some of the world’s greatest art. Even then, there is a thread running through that connects the earlier to the later.

He has said, “Artists have come to believe that they too, just like other people, need money and fame…what kind of artist or writer lives like that? Who is going to believe even a single line that he writes?… No, the artist’s needs are few: let there be something for him to eat and a place to live, and then every day he should circumambulate the city, the country, like the mendicant monks of old.”

I ask him about his long sentences. They are not sentences from a contemporary time, nor are they old. It seems to be the way he approaches the world, a philosophical act, not just a literary one.

He says, “First of all, you said, ‘the long sentence.’ To me, they are not long. For m,e it’s not short or long sentences, only too short or too long sentences. From my twenties, I work in my head, not as a writer at a desk, no, but as if someone were speaking inside, and this is unfortunately not a metaphor. I try to make contact with this speech in my head. If I am ready to understand and follow this speech, music, and content after 15-20 pages, then I start writing it down. One of the reasons my sentences are very long is that I became always closer and closer to speech. If you are telling me something meaningful, suggestive, you don’t use the dot; you don’t need it. The full stop, the comma, these are conventions. Long and short are conventions. I don’t want to say conventional sentences don’t work; they don’t work for me.

Elsewhere, he has said, “I believe this to be the language of a mass. A mass which has neither temple nor church, nor catechism, nothing at all.” So that, Krasznahorkai, in one sentence, can move between the dark and the light, connecting them seamlessly, as they are in human life.

He speaks too of melancholy, a word which is in the title of his book The Melancholy of Resistance. “A melancholic has time to sit only because of sitting; a melancholic in Europe is a little like the man in Japan who sits only because of the sitting. At this point here we can find a contact between European and Asian cultures.

For example, old Europe knew the very simple people in the provinces, the poor people, alone with animals in the village, peasants – that was a tradition, a tradition of peasants, they always had time for everything. You know, Tolstoy explains somewhere that once he walked on his land and he saw a peasant and this peasant was standing there, not moving, and Tolstoy went to him and touched his shoulder and Tolstoy wrote, ‘before I touched him, he was nowhere. Not outside of time, nowhere.’

As for the peasant, so for the melancholic. Melancholy allows us to be. Only to be. Because of being. Only to exist, to stay somewhere without a wish, without the knowledge that we are staying there.”

In Budapest, I say to him, “You’re one of the great contemporary writers, of whom there are few. And I use the word great very precisely, and knowingly. I so rarely find depth, narrative power, and a brilliance of language that approaches poetry, as well as a deeply philosophical vision, all in the same writer.

He says, “Ah, but I have a trouble. I am very alone because of this.

I am not lonely. Loneliness is not my problem. Maybe I was romantic during the time of Satantango. But not now. This is the other side of the humus of prose writing. What is our task with this vertical and horizontal? This is also a responsibility. To give a total picture about the earth. I’m not afraid of talking about my aspirations. I have an aspiration to write a total picture of our human world. I’m interested in what happens at the border of the human and the non-human. Yesterday, I spoke of elements in a relationship of non-closure. Sometimes I feel there is a non-closure relation between a point in the human world and a point in the non-human world. I am very interested in this fact. This is also a task for us.”

Towards the end of the talk at our Almost Island Dialogues in New Delhi, he said, “I don’t know why in my last years I am so helpless in the face of beauty.” This is the master of apocalypse, who is holding not only devastation and suffering but also beauty’s light and transcendence, both equally real in our human world.

The great works of literature most often come from societies that have faced great suffering, war, and political devastation. This Nobel Prize for Krasznahorkai should urge us to look outside our favourite Anglophone world of literature, its decadent and exhausted realism, outside the names that recur with machine-like repetition in the press or social media. This obsession not only narrows our reading and therefore our vision, it also narrows our possibilities as writers here to find our own voices and forms.

I would like to name Krasznahorkai’s brilliant translators: George Szirtes, Ottillie Mulzet and John Batki, without whom we would not have the pleasure of reading this profound writer.

Sharmistha Mohanty is a poet and prose writer whose most recent books include Extinctions and The Gods Came Afterwards. She is the founder-editor of the online literary journal Almost Island and the initiator of the Almost Island Dialogues, an international writers’ meet held annually in New Delhi.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting