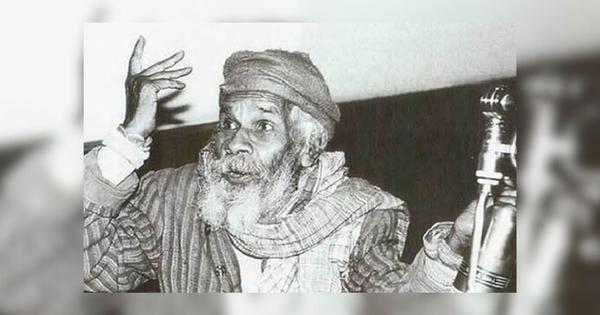

He wrote in two languages and lived in none. He walked barefoot through the burning questions of his time, clothed only in rage and tenderness. Born Vaidyanath Mishra under a thatched roof in a Bihar village, he became Yatri in Maithili and Nagarjun in Hindi, a people’s poet who spat fire and whispered grief in the same breath. A Buddhist monk turned Marxist, he could chant the Dhammapada and denounce the state with equal ease. He wandered not just across geographies but through the inner map of a fractured nation, speaking for farmers, women, fakirs, insurgents, and the landless.

Nagarjun’s literary output was vast, fearless, and genre-defying. His major poetry collections include Yugdhara, Kal Aur Aaj, Satrange Pankhon Wali, Talab Ki Machhliyan, Khichri, Viplav Dekha Humne, Hazar Hazar Bahon Wali, Purani Jutiyon Ka Koras, Tumne Kaha Tha, Akhir Aisa Kya Kah Diya Maine, Iss Gubare Ki Chhaya Mein, Yeh Danturit Muskaan, Main Military Ka Boodha Ghoda, Ratnagarbha, Aise Bhi Hum Kya, Bhool Jao Purane Sapne, Apne Khet Mein Chandana, Fasal, Akal Aur Uske Baad, Harijan Gatha, Badal Ko Ghirate Dekha Hai, Aaj Main Beej Hoon, and Mantra Kavita.

His novels, raw, rooted, and deeply political, include Rati Nath Ki Chachi, Balachnama, Baba Bateshar Nath, Himalaya Ki Betiyaan, Nai Paudh, Varun Ke Bete, Dukh Mochan, Ugratara, Jamania Ka Baba, Kumbhi Pak, Paro, Asman Mein Chanda Tare, Abhinandan, Imaratia, Sita Usko, and Navturiya. His essays were compiled in Ant Hinam Kriyanam, Bum Bholenath, and Ayodhya Ka Raja.

In Maithili, he wrote Patrahin Nagna Gachh and Chitra (poetry), and Paro, Navturiya, and Balachnama as novels, several of which he later reworked in Hindi. His explorations of agrarian and cultural realities also appeared in Desh Dashkam and Krishak Dashkam.

Nagarjun was not merely a writer; he was a movement, a mirror, a milestone. In every line, he demanded we listen to the earth.

People’s fire

On the rainy morning of June 11, 1911, in the Mithila village of Satlakha, beneath the shade of jackfruit trees, a boy was born. Vaidyanath Mishra came into the world not with incense and ceremony, but with the aroma of earth, red soil, sweat, and harvest.

Born to Uma Devi and Gokul Mishra in the Gram Panchayat of Tarauni, Darbhanga district, the boy spent most of his childhood in his maternal village of Satlakha. He lost his mother at the age of four. His father, a wanderer by nature, could not care for him, so Vaidyanath grew up on the kindness of relatives and the strength of scholarships, rewards for his brilliance as a student.

He would grow up to rename himself Yatri, the traveller. Later, upon embracing Buddhism, he became Nagarjun, the name under which he wrote his most enduring works. From monk to Marxist, his journey was never linear but always purposeful. He studied Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit, first under local scholars and then in Varanasi and Calcutta, where he worked part-time while pursuing his studies. He later married Aparajita Devi, and together they raised six children.

But more than a life of names and milestones, Nagarjun became a voice, a thundering, lyrical protest rising from India’s postcolonial fields and factories. His pen answered no official summons; it responded only to hunger, grief, injustice, and revolution.

He was moulded by the silences of village nights, the thud of pestles on husked grain, and the whispered rage of the landless. His words carried the ache of walking barefoot on cracked ground, of waiting for rain that didn’t come. Long before it became fashionable to romanticise the rural, Nagarjun lived its most bruising truths and wrote them without apology, without pause.

Nagarjun remains one of the most iconic and radical literary figures of 20th-century India. A towering presence in both Hindi and Maithili literature, he authored a vast body of work, including poems, novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, literary biographies, and children’s literature. He is remembered as Janakavi, the people’s poet, and is widely regarded as the most powerful and modernist voice to have emerged from Maithili.

He died on November 5, 1998, but Nagarjun’s fire still burns, in verses, in voices, and in every barefoot protest that dares to speak truth to power.

The geography of the tongue

Yatri’s gift to Maithili poetry was not just lyrical. It was seismic. He gave its musical soil a politics. In verses that carried the fragrance of rice husks and village wells, he exploded the false peace of caste hierarchies and feudal nostalgia.

He once wrote:

पत्रहीन नग्न गाछ छी हम

जनम-जन्मान्तर सँ

बिनु कोनो अपेक्षा,

ठाढ़ छी – आसमान दिस तकैत।

I am a leafless, naked tree,

standing for lifetimes,

expecting nothing,

staring at the sky.

In a conversation from almost 15 years ago, acclaimed scholar and critic Professor Namvar Singh told me, “Nagarjun made language accountable. He didn’t decorate it; he made it confess.”

He spoke not just of Nagarjun’s style, but of his moral force. His command over both Hindi and Maithili didn’t dilute either; it deepened both. He wrote, Singh said, “from the mud between the two tongues”, not standing above them, but rooted within them.

For Nagarjun, switching languages was soul-shifting. In both, he unmasked the hypocrisy of the upper class and reclaimed the vocabulary of the poor. Where other poets elevated language, Nagarjun pressed it into the service of the barefoot and the bruised.

Monkhood, Marx, and the Mithila wind

In the 1930s, Vaidyanath Mishra left his village of Taruni in search of silence. He became a Buddhist monk in Sri Lanka, learnt Pali, philosophy, and renunciation. That’s when he adopted the name Nagarjun, a tribute to the ancient dialectician whose logic once dismantled illusion.

But the silence didn’t last.

Back in India, renunciation gave way to rebellion. He shed saffron for red. Monkhood melted into Marxism. He no longer chanted; he chiselled verses. His target? The powerful. His prayer? Justice.

He walked with farmers in Andhra Pradesh. He listened to the aching stomachs in Darbhanga. He roared against zamindars, capitalists, and state machinery. During the Emergency years (1975–77), while many intellectuals fell silent or fell in line, Nagarjun’s pen burned through fear like camphor.

His most unforgettable poem from that time?

इन्दु जी, इन्दु जी, क्या हुआ आपको?

सत्ता के मद में क्यों भूल गई बाप को?’Indu ji, Indu ji, what happened to you?

In your intoxication with power, have you forgotten your father too?

This was no veiled allusion. It was a dagger made of ink. A direct address to the Prime Minister herself, Indira Gandhi. At a time when censorship reigned, when poets were jailed or silenced, Nagarjun, already imprisoned for his activism, remained irrepressible.

Yet Nagarjun was not only a political poet. He was a cultural detonator. His Hindi and Maithili poems merged revolution with rural rhythm. He took metaphors out of Sanskrit halls and planted them in paddy fields.

As the Maithili poet and biographer of Nagarjun, Taranand Viyogi observed: “Yatri made Maithili sweat. He dragged it out of its silken salons and into the sunburnt soil.”

And Shivshankar Srinivas, a fiction writer in Maithili, recalls his first meeting with Nagarjun: “He came like a faqir, khadi kurta, jhola, barefoot, but carrying the weight of a thousand poems. His words were not crafted; they were harvested.” Shivshankar Srinivas remembers a local poetry reading where a new poet performed a delicate, abstract verse. Nagarjun, smiling, offered a single, unforgettable line of advice: “Make sure your metaphors wear slippers. The barefoot will understand you better.”

Vyomesh Shukla, well-known Hindi poet and Pradhan Mantri of the Nagari Pracharini Sabha in Varanasi, said it best: “Nagarjun pulled poetry out of books and threw it into the fields. There, it sweated, it starved, and then it rose as a slogan. He was not merely a poet; he was the carrier of public consciousness.”

Prose, people, and the politics of desire

His first novel, Paro, written in Maithili in 1946, was more than a literary landmark. A story of a widow’s defiance and dignity, Paro remains one of the first modern Maithili novels to address women’s sexuality not with shame, but with compassion and candour.

Maithili scholar and writer Kathakar Ashok wrote in his seminal essay “Manorthak Paro”, “It was the first time in a Maithili novel that a woman character truly spoke. Not as a symbol, not as an ornament, but as a complete human being. Paro marked the birth of voice in the Maithili Novel.’ For Ashok, Yatri’s Paro was not just a character; she was a turning point.

The novel’s protagonist is not mythologised. Paro is made human, desiring, fallible, and dignified. There is no divine retribution waiting in the wings. Just the everyday patriarchy of rural Bihar, and her stubborn refusal to yield to it.

If Paro was a quiet rebellion, Ratinath Ki Chachi (1956) was a howl.

In this Hindi novel, Nagarjun portrayed a young man’s obsessive love for an older woman, his aunt by social designation. Again, it was not the romance that shocked readers; it was the honesty. No metaphor, no gauze of morality.

Then came Balchanma, a novel of a different register. Written in the late 1950s, it follows the story of a boy from the margins, growing up under the twin shadows of caste and poverty. If Ratinath Ki Chachi asked questions about intimacy, Balchanma asked questions about dignity.

The novel did not seek pity. It demanded recognition. Balchanma, the protagonist, is not a tragic figure. He wanders through the landscape of postcolonial India, part outcast, part witness.

Through these novels, Nagarjun did what few writers of his time dared: he walked the edge between the personal and the political, between kamna (desire) and karuna (compassion). He showed us that the inner world of yearning is not separate from the outer world of struggle.

What made Nagarjun unforgettable was the sheer range of his emotional and political register. His writing held fury, but it also revealed unguarded tenderness. His pen wandered easily between the street and the courtyard, the prison and the prayer room. He wrote of farmers and fakirs, lovers and lunatics, beasts and bureaucrats, hunger and hallucination.

In Maithili, he wrote a seismic poem called “Vilap”, a dirge born of the horror of child marriage in Mithila.

अगड़ाही लगौ बरू बज्र खसौ

एहने जातिपर बरू धसना धसौ

भूकम्प हौक बरू फटौ धरती

माँ मिथिले रहियेक’ की करती!Let lightning strike instead,

Let an earthquake devour such a caste,

Let the earth crack open and swallow us whole

O Mother Mithila, what would you have done with this shame?

Nagarjun once said:

पेट त हिंदी सँ भरैत अछि, मुदा कोढ़-करेज खखोड़ि जे निकसैत अछि, ओ मैथिलीए में अबैत अछि।

The belly may be filled by Hindi, but when the scabs are scraped off the chest, what oozes out is always in Maithili.

Yatri ji didn’t write about people, he wrote from within them,” says Kathakar Ashok. “His images rose from the soil, rough and real. For him, language was a weapon, a tool, and sometimes, a hymn.”

Taranand Viyogi adds, “Even when Nagarjun stood in Delhi’s literary circles, Maithili’s mud was still on his feet. His metaphors smelled of cow dung and justice. That’s why they lasted.”

Viyogi goes further to argue that Yatri didn’t merely write in Maithili, he rebuilt it. He dragged it out of the confines of royal courts and classical archives, and placed it firmly in haats, bazaars, and protest sites. He gave Maithili a pulse, a politics, a people. He returned it to those who had been taught to be ashamed of it. And in doing so, he restored its future.

Nagarjun died in 1998 but his journey didn’t end. Because a yatri, a traveller, never stops.

सभ सँ प्रिय निज देश

Most beloved is one’s own land.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting