For far too long, studies on India’s Partition have remained stuck to the study of its causes, initially in the frame of “high politics” of negotiations and later in reference to some regions, viz. Punjab, Bengal, and United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh). Subsequently, some inadequate attention was paid to Sindh and Bihar. In fact, the sufferings of Hindu minorities of Sindh are still waiting for meticulous attention from professional historians (Nandita Bhavnani’s 2018 book, Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India, is an exception; the author is a chartered accountant). Yet, predominant historiographic concerns remained essentially confined to exploring causation. Francis Tucker’s twin-volume account remains inadequately tapped by the historians working on the Partition. Why such a skewed attention to causation rather than to consequences? Does this possibly have to do with narrativising the blame games as per the convenient prejudices of the respective groups?

This has been essentialised that the Indian National Movement was a non-violent mass movement. Ironically, India won freedom in 1947, with religion-based territorial partition, killing and displacing each other on a very large scale. The politics around the wounds of that violence continues to create Hindu-Muslim fratricide intermittently to date. If at all, Partition had become so very inevitable at any point in time, why couldn’t the British and Indian leadership find peaceful ways of the transfer of population? Didn’t they (more particularly, Mountbatten, Radcliffe, Jinnah and also the Hindu Mahasabha-RSS; the last two acquired a lot of strength post-1938) have European, Ottoman or other examples of relatively less violent transfer of population (coercive, forceful or compulsive uprooting of population, in itself, is violence!)?

A violent history

The biggest sufferers of the Partition – the common people and more particularly the women – got less attention in historical works and more in fiction. Can it be argued that initially, relative historiographic inattention to study the human sufferings had to do with shame and sense of guilt that once human sufferings are explored, the verdict of history will read guilty for all players of the respective religious communities – Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and for the political forces led by the segments of the elites of the respective religious communities? This provocatively debatable proposition gets little more saliency when it occurs to the students of history that, except for the Garhmukteshwar pogrom, an important (politically and demographically) region, Uttar Pradesh skipped the Hindu-Muslim fratricide in the wake of Partition. (Gyanesh Kudaisya called it India’s “Heartland”). Whereas, Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman, the Lucknow-based tall leader of the Muslim League, in his memoir, Pathway to Pakistan (1961), was quite candid in “confessing”, “All students of Indian politics know that it was from the UP that the League was re-organised. Mr Jinnah took full advantage of the situation and started an offensive which led to Pakistan.” Khaliquzzaman noted this in his Preface, attributing it to Maulana Azad (India Wins Freedom). May someone therefore argue, Jinnah was rather a “borrowed captain” of the team called UP Muslim elites affiliated to the Muslim League, in pursuit of “creating a new Medina”?

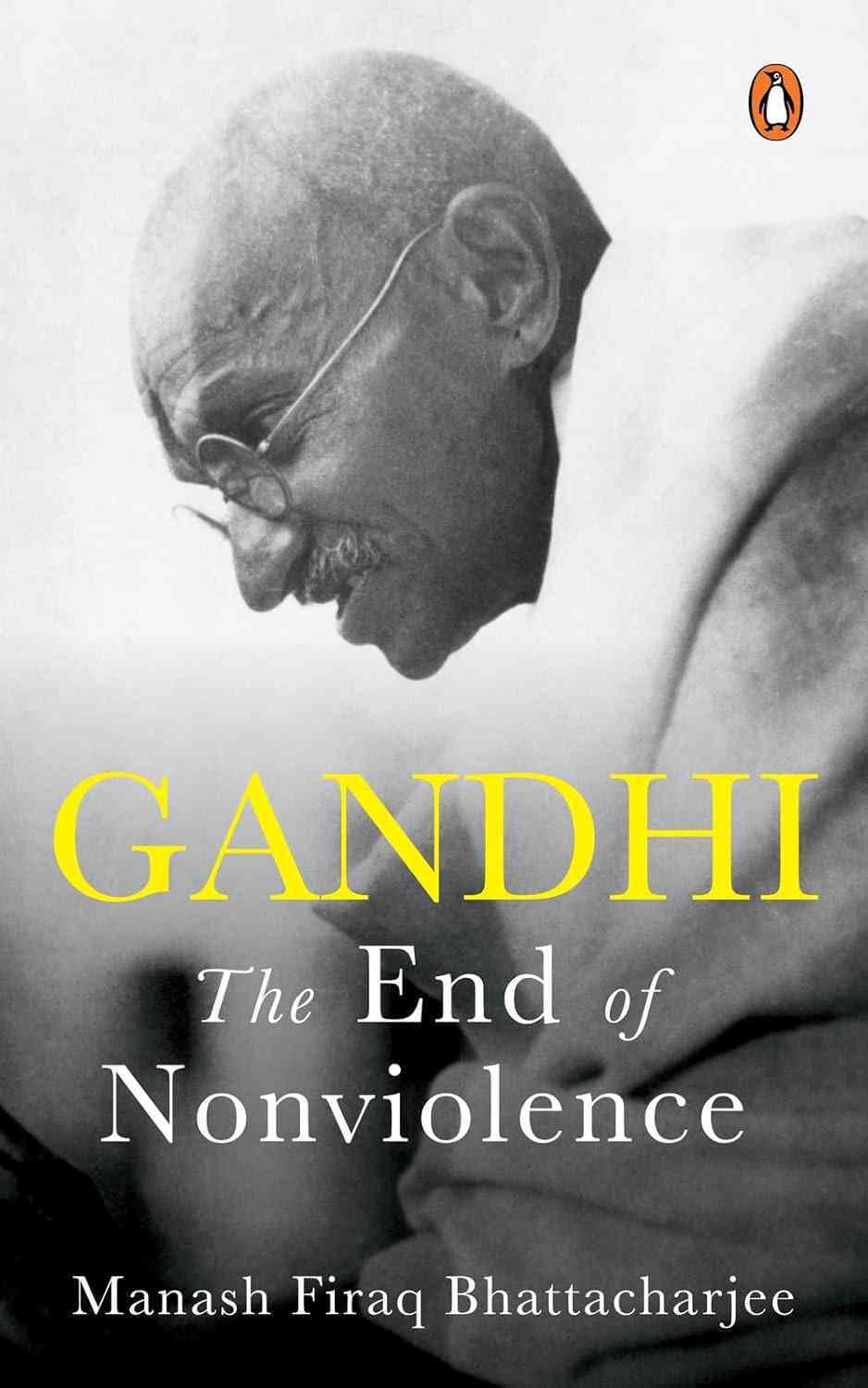

Be that as it may, Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee’s Gandhi: The End of Nonviolence, rigorously well-researched book in wonderfully lucid prose has come out with marvellous articulation on the communal violence of 1946-47. This book engages with Gandhi’s intervention to stop the pogroms in Bengal, Bihar, and Delhi (he was assassinated before he could reach Punjab and Sindh to do the same). Bhattacharjee also explicates on Gandhi’s “failures”, despite his “messianic interruption”. The author says that India’s partition was a failure of leadership that didn’t anticipate the repercussions. In fact, not only common people, but even the educated leadership of the Muslim League remained unclear about the exact territory of the proposed Pakistan. For instance, a Vice Chancellor of the Aligarh Muslim University, Nawab Ismail Khan, kept asking Jinnah to categorically define the territory, but Jinnah refused to give any concrete assurance on that. At the same time, vaguely assuming the Muslim majority provinces of Bengal, Punjab and Sindh were going to the proposed Pakistan, many leaders critiqued the viability of the state of Pakistan. They include Tufail Ahmad Manglori (1868–1946; Musalmanon Ka Raushan Mustaqbil), Maulana Hifzur Rahman Seohaarvi (1901–1962; Tehreek-e-Pakistan Par Ek Nazar), Maulana Sajjad (1880–1940; some open letters to Jinnah in his periodical, Naqeeb, Patna), and Shaukatullah Ansari (1908–1972; Pakistan, the Problem of India). Except for the one by the last-named, other critiques are in the Urdu language (Manglori’s has been rendered into English by Comrade Ali Ashraf, Towards a Common Destiny, 1994).

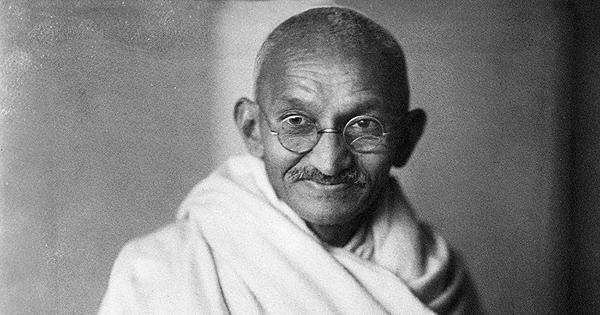

Anyway, Gandhi’s intervention was not backed by the resources of state machinery. In fact, Gandhi opined that if fear of the police and criminal justice system is preventing the hate-filled people from resorting to violence, then this in itself is a great cause of worry, and that cannot be taken as assurance of peace. He was the only moral force, with some of his dedicated followers. This is where another question emerges: why didn’t Jinnah, or for that matter other Muslim leaders of the Muslim League, rise to save non-Muslim (Hindu and Sikh) minorities in the Sindh and Punjab parts of what became Pakistan after August 14, 1947? If Muslim minorities of Bihar and Delhi had Gandhi (and Nehru) putting every possible effort to contain the pogroms and the top Congress leaders were indignant at the massacres and displacements, then why didn’t the Hindu and Sikh minorities in those parts find some Muslim League leaders making efforts towards doing the same? Far from this, Jinnah was particularly dismayed at Khaliquzzaman (President of the Muslim League in December 1947) praising Gandhiji for his efforts to contain the pogroms.

Interpreting violence

Chapter after chapter, Bhattacharjee brings out moral-philosophical commentaries to interpret the violence, the remorse (and lack of it). Such riveting narrations keep the readers fully absorbed in the book. The ironies he points out leave the readers amazed. His interpretations of the words of Gandhi open up new layers of meaning. He dishes out a series of quotable quotes. Sample these: “Gandhi was mourning two things together, the violence of partition and his own irrelevance” or “…The phenomenology of retributive politics, or the politics of hate, is not natural but ideological …forgetting is the price to pay in the politics of friendship. Gandhi adds a strict third criterion: friendship can’t be based on a vacillatory promise”.

Bhattacharjee adds to our insights by writing profound words. He argues, Gandhi was into the politics of listening, whereas in modern politics, “leaders and ideologues meet people to preach and lecture, not to listen”. And that he had the moral guts to say something harsh even to a victim. “Both communities were abandoned by their political leaders, uprooted from their homes, forced to face a calamity that was bewildering and lethal. Only a 78-year-old fragile but spirited man was listening to their woe, reproaching them, receiving their abuse and anger, insisting on love and peace, reminding them of the moral precepts of their own and even others’ religion”.

Let it be pointed out that certain long comments of Bhattacharjee in his endnotes are as useful for future research as much as for re-assessment of some secondary works. Just one instance, he critiques the “communal mythology” created by Shabnum Tejani’s 2007 book on Indian Secularism, wherein she characterises Jinnah’s “Direct Action” as a call for “peaceful mass campaign”. Bhattacharjee then befittingly concludes in the endnote commentary, “Whether Pakistan lived up to Jinnah’s idea or not is less about Jinnah’s intentions, and more about the disfigured nature of his idea”.

Bhattacharjee’s book helps us rediscover Gandhi in novel ways, offering insights to make sense of the fractious society and polity of contemporary times. Bhattacharjee claims in the Preface that the book “is a metahistorical assessment of the politics of historiography”. He is spot on! His 118-page-long introductory chapter, “rift in the lute”, could be made into a standalone book on the theme of violence and philosophical ways to get outraged against violence. The philosophised and theorised articulation is not a burdensome reading; it is lucid in beautiful poetic language. Each chapter has poetry-like headings lifted creatively from the primary sources. Not many rigorous academic history writings can claim to have such beautiful prose.

Mohammad Sajjad is a Professor at the Centre of Advanced Study (CAS) in History at Aligarh Muslim University. He is also the author of Muslim Politics in Bihar: Changing Contours and Contesting Colonialism and Separatism: Muslims of Muzaffarpur Since 1857.

Gandhi: The End of Non-Violence, Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee, Penguin India.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting