Josnra Bibi’s eyes lit up when she saw us. She believed we had news of Sunali Khatun, her 25-year-old daughter stranded in Bangladesh.

“When will she be back?”

Sunali, who was a domestic worker in Delhi, was detained by the police on June 20 from the Bangali Basti in Rohini along with her husband, Danish, and eight-year-old son, Sabir.

Since May, thousands of Bengali-speaking migrant workers have been rounded up in states ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party and asked to prove that they were Indian citizens – and not undocumented immigrants.

In several cases, workers have been declared foreigners within days and forced into Bangladesh, despite being Indian citizens.

Josnra Bibi claims that is exactly what happened with Sunali, her husband and son – despite the family having land records going back five generations.

The Delhi raid

When the police arrived in the Rohini slum where Sunali lived, they showed them their Aadhaar cards and ration cards.

Sunali’s sister Karishma, who used to live next door to her in Rohini, said that the police demanded to see their birth certificates, which they did not have.

Sunali’s son’s birth certificate was lost to a fire in the slum just weeks before the police raid. But the police refused to believe them.

Six days after they were detained, Sunali, Danish and Sabir were sent to Bangladesh on the basis of an order passed by the Foreigners’ Regional Registration Office.

The order as well as Delhi police records viewed by Scroll say that the family confessed that they belonged to Bagerhat in Bangladesh.

Sunali’s family members staunchly deny the allegation. They say they are from West Bengal’s Birbhum district – a claim endorsed by the local Rajya Sabha MP, Samirul Islam, who moved the Supreme Court to challenge her expulsion.

The May 2 home ministry directive under which such drives are being conducted says that before taking any action, the police must contact local authorities in the individual’s home state to verify their citizenship status.

But an officer at a police station in Sunali’s village in Birbhum, who requested not to be identified, told Scroll that the Delhi police had not contacted them for any sort of verification before expelling Sunali, her husband and their son.

Karishma alleged that Danish’s and Sunali’s so-called confession was made up by the police. “They detained a lot of people from our slum,” she said. “Those who gave bribes were let off. The police forced this confession out of my sister because she could not pay a bribe.”

An officer at the KN Katju Marg police station in Rohini denied the allegation.

As Bengali-speaking migrant workers are detained in BJP-ruled states and accused of being illegal immigrants, Scroll travels to rural West Bengal to meet families forced to prove they are Indians. Read the series here.

Weeks after her daughter’s detention, Josnra Bibi returned to her village. With her was Anisa Khatun, Sunali’s seven-year-old daughter, who had escaped her brother’s fate because she was not with her mother during the raid.

Scroll travelled to Paikar village to examine the family’s claims. We found villagers who confirmed that they had lived there for several generations, land records that attested to the same – and even the midwife who delivered Sunali 25 years ago.

Citizenship test

Sunali Khatun’s parents live in two rooms of a mud hut in Paikar village.

Her father, Bhodu Sekh, spends his days sitting on his haunches, watching over the household and chewing tobacco.

Age has slowed him down but over three decades ago, the 61-year-old was the first from his family to make the move to Delhi.

As a ragpicker in the national capital, he made the kind of money that was impossible to earn if he had continued to work as unpaid labour for an influential family in the village.

In the years that followed, the couple frequently travelled from Paikar to Delhi and back. “We never faced any problem in Delhi before,” Josnra Bibi said. “Nobody has called us Bangladeshis in the past.”

Their daughters, Sunali and Karishma, moved with them and eventually took up work in the city.

According to her Aadhaar card, Sunali Khatun was born in 2000.

For her to be considered an Indian citizen by birth, the Citizenship Act states that at least one of her parents must have been an Indian citizen at the time of her birth.

Bhodu Sekh was born in the village, while Josnra Bibi moved to Paikar from Murshidabad after her marriage. But, like most people from rural India, they were born at home and do not have birth certificates.

Both husband and wife possess voter cards. Scroll verified their authenticity by searching through electoral rolls on the Election Commission of India’s website. We also found their names on the 2002 voter list for the Murarai Assembly constituency of West Bengal uploaded online by the ECI.

The names of Sunali’s grandparents are also on the list.

Bhodu Sekh also showed us a land deed for the house they live in. It had his name on it. “We have faced a lot of difficulties in life but we never left this house,” added Hasanehena Bibi, Sunali’s grandmother.

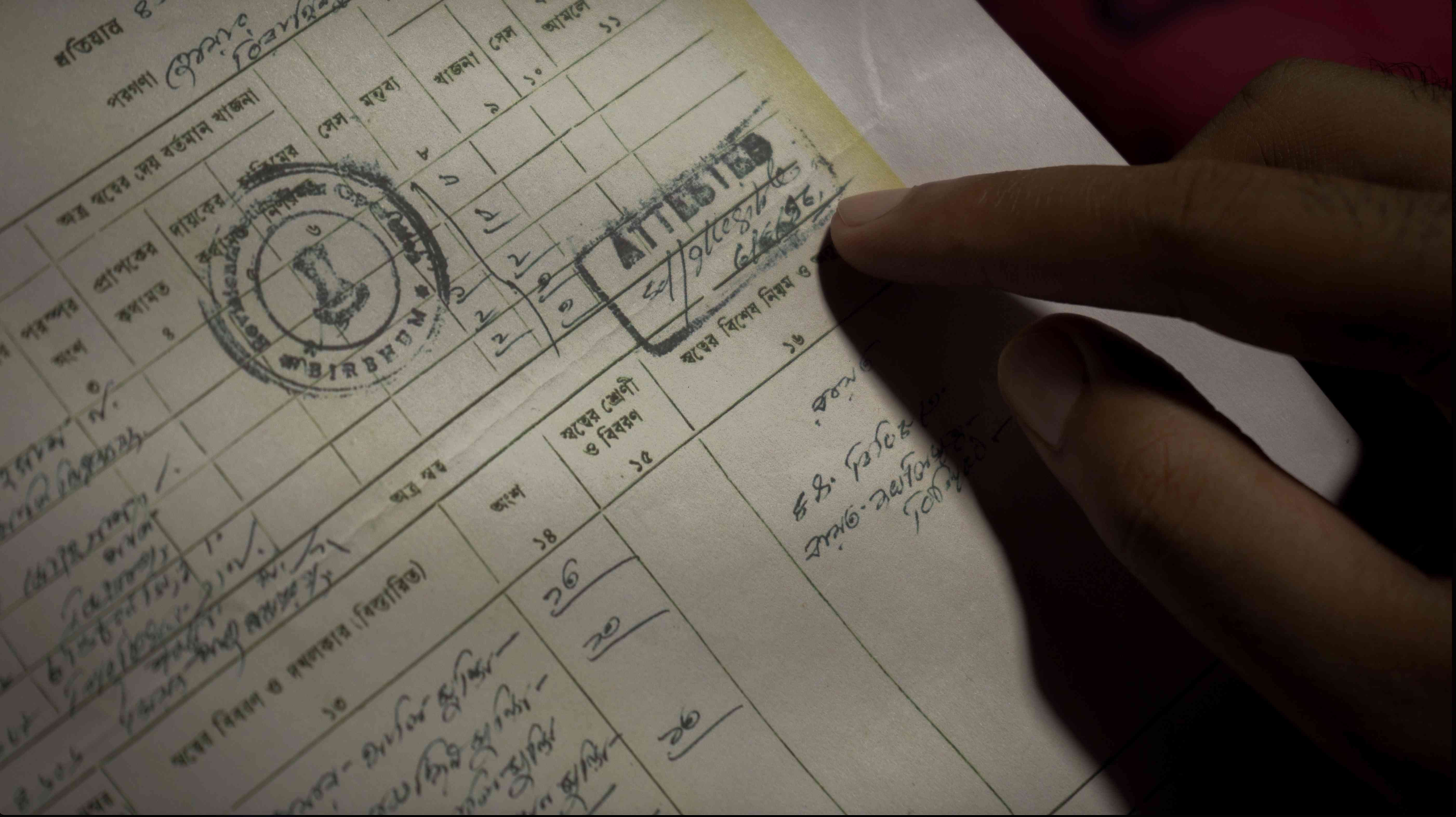

After his daughter was detained in Delhi, Bhodu Sekh filed a right to information request with local officials who maintain land records. He found more proof of his ancestral claim to the house. The documents he got, one of which is dated 1956, show that the family has lived in Paikar for several generations – going back to Sunali’s great-great-great grandfather, Amiruddin Sekh. Scroll has seen the documents.

“Even Modi himself will not be able to show you so many documents,” said Rocky Sekh, a neighbour and distant relative of the family.

What the village remembers

The one document that they did not have was a birth certificate for Sunali.

But along with Josnra Bibi, we went to the government hospital in Paikar in search of the midwife who delivered her.

She had not turned up that day. We walked a little distance to her home, where we found Bhagirathi Ravidas recovering from a bout of fever.

For nearly five decades, the frail old woman has helped women in the village deliver children. “I delivered Sunali as well as her other two children,” she said, pointing to Josnra Bibi. “They are not Bangladeshis. I have seen their family here for a long time.”

At the Paikar gram panchayat office, a worker named Subhendu Das also told us that Sunali’s family had been living in the village for generations. “Her father used to go around the village selling pickles before they left for Delhi,” he said.

Other residents of the village came forward to express sympathy for the family. A young man, who did not wish to be named, said they had been targeted only because of their faith.

“When we Muslims go to places like Delhi for work, people call us Bangladeshis,” he complained. “Is that fair? There are no Bangladeshis here. But closer to the border, you will find Hindus who came from Bangladesh. Should we start calling them Bangladeshis?”

Mounting worries

Despite all the evidence that the family has gathered, Sunali and the others are still stuck in Bangladesh.

Things took a turn for the worse on August 21, when the police in Bangladesh arrested them from the border district of Chapainawabganj. There too they have been accused of being “illegal infiltrators”, The Indian Express reported.

Meanwhile, her father’s habeas corpus petition in the Calcutta High Court, which he had filed in July, is scheduled to come up for hearing on September 10.

But Samirul Islam, the Rajya Sabha MP and chairperson of West Bengal’s Migrant Workers Welfare Board who helped with the petition, worried that the wheels of justice were moving too slowly.

“My biggest concern is that Sunali is pregnant,” he said. “What if she delivers in Bangladesh? What will be the legal status of that child?”

Josnra Bibi breaks into tears at the thought. “I wonder what state she is in,” she said.

Since they were separated over two months ago, the mother and daughter have spoken to each other just once. That was when a stranger called from Dhaka, asking them for Rs 35,000 in exchange for helping Sunali and the others cross the border and return to India. They did not have the money.

The last time Josnra Bibi saw Sunali was in a July 19 video circulated on social media. “My grandson looked so thin,” she said. “He used to be chubby before. I don’t know how much longer it will take for them to come back.”

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting