The two Rajput brothers were broadly on the same page about the Janata Dal (United) candidate in the Sursand Assembly constituency of Bihar. Both agreed that he had done nothing for their village of Chhotki Bhitha. Still, the younger one will vote for him because he supports the Bharatiya Janata Party, the JD(U)’s ally.

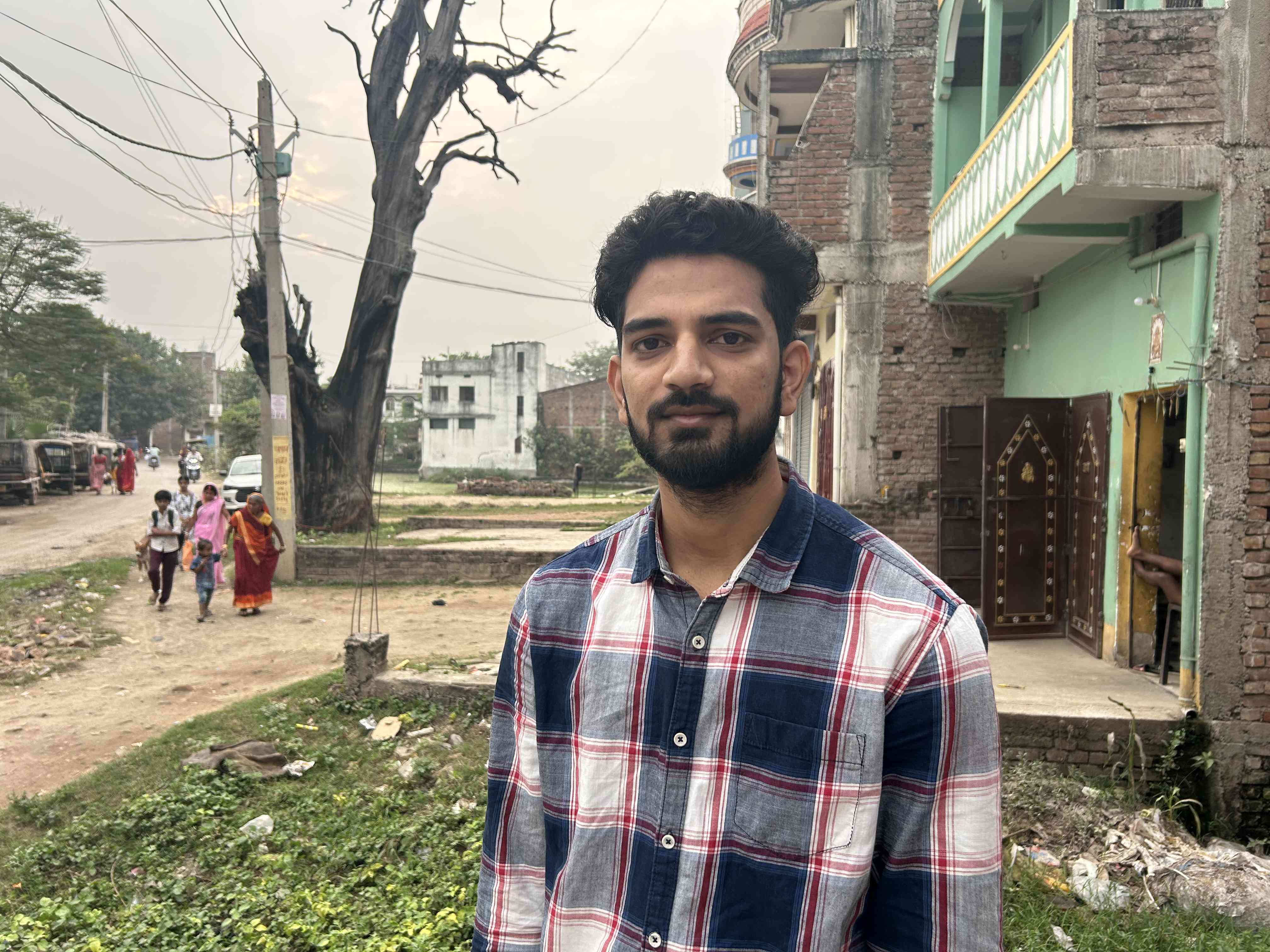

Till 2024, Alok Singh, the elder brother, used to favour the BJP as well. However, this time the 32-year-old construction contractor is leaning towards Jan Suraaj, the party floated by election consultant-turned-politician Prashant Kishor.

“He was the first to talk about increasing old age pension and stopping migration,” Alok said, explaining what he admired about the man. His younger brother chipped in to say that while he too liked Kishor, such a new party could not win in the state. “Even if he cannot form the government, my vote will go to him,” Alok retorted.

In other villages nearby, Muslim and Yadav residents, in turn, complained about the nominee from the Rashtriya Janata Dal. The two communities are considered core supporters of the party. While Muslims said that the candidate was never around when they needed him, Yadavs admitted that they were not happy with a Muslim getting the ticket.

But in stark contrast with the upper-caste voters, most of them expressed little to no interest in Prashant Kishor. “How can we trust him when he is not contesting the election himself?” asked Hasan Ansari, 23, a student of pharmacy. The Jan Suraaj founder decided against entering the fray after initially fanning speculation that he would.

As Scroll travelled across Bihar, voter response to Jan Suraaj was along similar lines. Those who showed interest in the new party were predominantly from the upper castes. Most Dalits, Muslims and Other Backward Classes were non-committal or even hostile towards it.

If this pattern holds, Prashant Kishor is likely to hurt the BJP in his political debut, given that Bihari upper castes largely tend to favour the Hindutva party.

Denting the BJP

Ironically, Kishor first shot to fame because of his work with the BJP. In 2014, he crafted Narendra Modi’s publicity campaign as the Gujarat chief minister successfully ran for prime minister. He subsequently started a political consultancy firm, Indian Political Action Committee or I-PAC, and worked with several other politicians, including those opposed to the BJP.

That was until 2021, when he announced his exit from the trade. About a year later, he began traversing Bihar with his Jan Suraaj Abhiyan, which eventually metamorphosed into the political party that he runs today.

Kishor promises to improve primary education, stop low-wage migration and encourage entrepreneurship in the state by expanding access to credit if voted to power. On the question of social justice, he has repeatedly claimed that his party is committed to providing proportional representation to all communities.

However, Jan Suraaj’s choice of candidates for the upcoming elections does not fully bear this out. Around 41% of them are from the upper castes, according to an Indian Express analysis, even though they make up only about 15.5% of the state’s population.

Only the BJP has handed a higher proportion of its tickets to upper castes. Watchers of Bihar politics say that the overrepresentation of this group in both Jan Suraaj and the BJP could split its vote between the two outfits.

Sitamarhi-based activist Brajesh Kumar Sharma said that in the northwest Tirhut division, which has a higher proportion of upper castes than the state average, Jan Suraaj’s entry has led to three-cornered contests.

Tirhut is the state’s largest administrative division and sends 49 MLAs to the Assembly. Most seats here typically see straight fights between the National Democratic Alliance and the Mahagathbandhan.

Political scientist Ashwani Kumar, author of the book Community Warriors: State, Peasants, and Caste Armies in Bihar, suggested that Kishor’s own caste identity may give him an advantage in Tirhut. “As a Brahmin, Kishor holds some social leverage there, considering the sizeable presence of Brahmins in that area,” he added.

In Sitamarhi, a part of Tirhut, Scroll met Brahmin supporters of Jan Suraaj. “I want to see a new face do well in politics,” said Deepak Kumar, 22, who sells SIM cards in the town. “I like Prashant Kishor because he talks about young people and education.”

The interest in Kishor has convinced local BJP workers that Jan Suraaj is hurting their party.

“Any votes that go to Jan Suraaj will damage the NDA [National Democratic Alliance],” argued Avnish Kumar, a member of the BJP’s district committee and the owner of a cyber cafe. “Caste decides everything in politics here. Most of Prashant Kishor’s votes will come from Brahmins and Bhumihars.”

The idea that Jan Suraaj may be damaging the BJP gathered more steam last month after four candidates from the party withdrew their nomination papers. Kishor himself alleged that BJP bigwigs like Amit Shah were “threatening and coercing” his leaders into pulling out of the polls. On November 5, another candidate from the party backed out and joined the BJP.

‘Look at his history’

Notwithstanding his run-ins with the BJP, Scroll found that Muslims remain mistrustful of Prashant Kishor. In Bihar, most voters from the community have supported Lalu Prasad Yadav and his Rashtriya Janata Dal for over three decades.

Yadav is admired by Muslims for arresting Lal Krishna Advani, a founding member of the BJP, during his infamous yatra at the peak of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement in 1990. He is also credited for ensuring that no major communal riot took place during his party’s 15-year rule.

When Kishor began his yatras back in 2022, he made several attempts to reach out to Muslims, urging them to stop letting the fear of communalism guide their political choices. He accused the Rashtriya Janata Dal of taking Muslim support for granted and vowed that his party would field about 40 candidates from the community to reflect their 17.7% share of the state’s population.

While Jan Suraaj has not exactly done that, it has still given tickets to more Muslims than any other major party in Bihar. That may not be enough to garner their support, though.

“He has given tickets but his attitude is anti-Muslim,” contended Shahbaz Alam, a resident of Bahadurpur village in Vaishali. “Just look at his history. He worked with Modi for a long time. Most Muslims think he will join forces with the BJP whenever it suits him.”

The 23-year-old was of the view that Muslims looking for an alternative to the Rashtriya Janata Dal would choose the more assertive Asaduddin Owaisi over Prashant Kishor. Owaisi’s party, the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, had won five seats in the 2020 Bihar elections.

Dalits, too, voice suspicion of Kishor because of his Brahmin caste. This despite Jan Suraaj putting up Dalit candidates from unreserved seats – a rare sight in Indian politics.

“That chotiyadhaari talks big but he is actually only a vote cutter,” said Pawan Paswan, a 26-year-old Dalit labourer working in Sitamarhi town. The Hindi word “chotiyadhaari” was a pejorative reference to the tuft of hair that is traditionally associated with Brahmin priests.

The lack of trust in Jan Suraaj is not necessarily a function of voters’ caste or religious identity. Some simply say that they don’t know enough about Kishor to believe that he can run the state.

“I have not seen his work yet,” explained Satish Kumar Singh, owner of a transport business in Durgapur, West Bengal, who was visiting his ancestral home in Nalanda. “What has Prashant Kishor really done other than helping politicians?”

A contender in 2030?

It is not as if Kishor, who has for months received wall-to-wall coverage from the mainstream media, has completely failed to influence Opposition voters. His focus on education and migration has found resonance among some young Biharis across the political spectrum.

However, Opposition voters tend to moderate their expectations from Jan Suraaj in the upcoming election. Suraj Kumar, a history graduate and an aspiring civil servant living on the outskirts of Patna, was more confident about Kishor’s prospects in the next election than this one.

“He may not do well this time but he will certainly form the government in 2030,” he declared. “Nobody before him has gained so much ground in just three years. If I ever enter politics, it will be from Jan Suraaj.”

In Raghopur, Rashtriya Janata Dal leader Tejashwi Yadav’s constituency, migrant worker Daya Yadav said he was gutted to learn that Kishor was not contesting the election. “I would have voted for him if he was in the race but now I will return to work in Gujarat after Chhath,” the 20-year-old added. “I will wait for another five years to vote for him.”

Anil Kumar Ojha, a retired professor of political science from Muzaffarpur, attributed this support for Kishor to two factors: his domineering media presence and the growing tendency among young people to distinguish their political choices from their families or communities.

“The internet and smartphones are producing free thinkers in society,” he said. “These days, more people think for themselves and want to separate themselves from the herd. This consciousness is now present in all communities even if there are gaps in access to education and information.”

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting