Habu Datta taught me the clarinet. The shehnai, the nakara and the tikara, I learnt from Mechobazar’s Hajari Ustad. I trained for two and a half years. By that point, I was bursting with pride. A lot of great ustads were given patronage by Muktagacha’s Jagat Kishore Acharya. I went to him with my cornet, shehnai and violin. It was during Pujo. I could play the cornet well. The Raja was strolling around the pond in the evening.

“What do you want?”

“Yes, I meant to say, I’ve practiced music for seven years and learnt so much. There’s no ustad like me in Bangla and probably not even in the whole of this country.”

“Has this chap gone crazy…what instrument do you play?”

“I can play every instrument in this world.” I had picked up this bad habit of boasting from the theatre.

“Come back at eight in the morning,” he said.

Although he had asked me to come at eight, I turned up at seven itself. I saw a person with a long, beautiful beard who was tuning the tarafs (auxiliary strings) of a sarod. The Raja was seated there along with all his courtiers. He was preparing to play raag Todi; I began quivering in excitement. The moment he tuned the instrument and just played a taan (flow of notes) from nikhad (seventh note of the octave) to Sa, I broke down crying. When he finished playing, I broke down, crying profusely, and hugged his feet.

“You are my guru! I will cook, clean, do everything else for you. Please just teach me how to play the way you did.”

“Don’t cry,” the Raja said. “I will make you his sakred (musical assistant-cum-disciple) right away.”

So I became his sakred that day itself. I must have been around sixteen–seventeen years old, then. The ustad’s name was Ahmed Ali. He was from Rampur. He was Abed Ali’s son. His forefathers had received patronage from Bahadur Shah. Ahmed Ali had a job with Ghughudanga’s Dulichand Marwari. Maestros like Ganapat Rao, Badal Khan, Tarabai would also come to listen to him play at Dulichand Marwari’s ashor (musical gathering).

At first, Ahmed Ali taught me how to cook roti, meat, pulao. He could cook well. I don’t eat meat – sometimes the roti and meat would remain undercooked. Whatever Sa Re Ga Ma he told me to play, I picked up within a year. Wherever Ahmed Ali played, I also went with him. I got twenty-five–thirty rupees by playing the tabla or the violin with him. He also kept his own earnings with me. He asked for money when he needed it. I listened to whatever he would play. After drinking tea in the morning, Ahmed Ali would leave for Kolkata. All the music that I had picked up by stealth while cooking or while sitting in the kitchen, I would play after he had left. I kept this up for four whole years. One day, while I was playing Todi, Ahmed Ali had come back.

He listened to me play from outside the house for an hour. Then, he knocked.

“You’re a thief, a dacoit.”

I come from a line of dacoits, after all. I stole money from my mother, of course, I would also steal knowledge.

“Leave,” he said.

I said, “I will not do it again. But, tell me, am I no good at it?”

“First prepare yourself. Focus on rewaj.”

I went to Patna and Banaras with him once. I saved four–five thousand rupees from playing at both places. “Let’s go to Rampur,” he said, and I went. The roof of his house was made of khola (clay tiles), and its walls were of mud. He kept me in a room at some distance from the house, near the latrine. The smell would make me ill and here was the Ustad asking me, “Allauddin, have some tea, you are not having any problems here, are you?”

“Well yes, from the smell…”

Meanwhile, I had run into the Ustad’s mother.

One day, I told him, “Gurudeb, take stock of all the money you handed me.”

“Is there any left? None of my other servants ever returned anything to me. They would say, all the money there was had been spent on food.”

I gave him a box full of gold coins. I handed him my earnings as well, as gurudakshina (an offering or honorarium to a guru). On top of that, I had stopped eating at the langarkhana. I ate with him.

His mother said, “He is a god! Would anyone else have ever returned this?” Both his parents were happy with me. After that, I was put up in a better room. I used to sew my own clothes and eat thick rotis. After around ten days, I saw a vehicle full of bricks come to the house. Guru ji ordered, “Allauddin, bring those bricks.” Ah! Such bad timing it was to return that ten thousand rupees to him. He was building a new house with that money. Then the masons and the building materials arrived. He said, “Allauddin, give them a hand.” Saying, “Yes Guru ji, of course,” I got to work. Lugging those heavy bricks around gave me colic pain. It is with me till this day.

You dears, learn to play well. Guru ji has built a school. He has drawn a number of talented artists to it. I never got the chance to do something like this.

One day, Ahmed Ali’s mother called me and said, “Listen, boy, when one doctor cannot cure your illness, then you have to go to another one. Whatever you had to learn from my son, you have learnt. Now go to someone else.” I thought they were going to kick me out of their house. I started crying, “Where will I go? To whom will I go?”

“Ujir Khan saheb is there. Go to him.”

Ujir Khan was also a poet. He had written a play named Bhartrihari. I went looking for Ujir Khan, but I could never get hold of him. The guard said, “Do you have a card? Otherwise you can’t meet him.” Six months passed like that. I still had six–seven rupees left from my earnings from the theatre. I thought, can a poor boy like me ever learn from him? But how would I show my face to people at home if I failed to make something of myself? I decided I would end my life. I bought two tolas of opium. That day, at dawn, I was performing the namaz, but my heart was not in it.

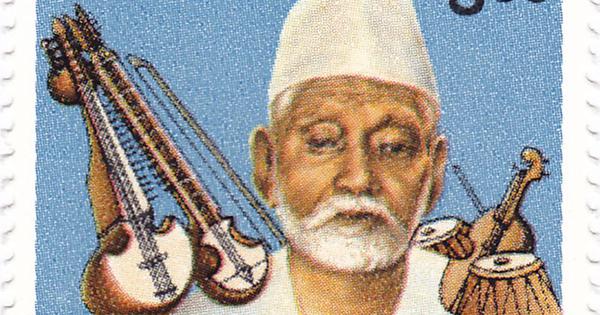

Excerpted with permission from My Life: Story of an Imperfect Musician, Ustad Allauddin Khan, translated from the Bengali by Hemasri Chaudhuri, Paper Missile/Niyogi Books.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting