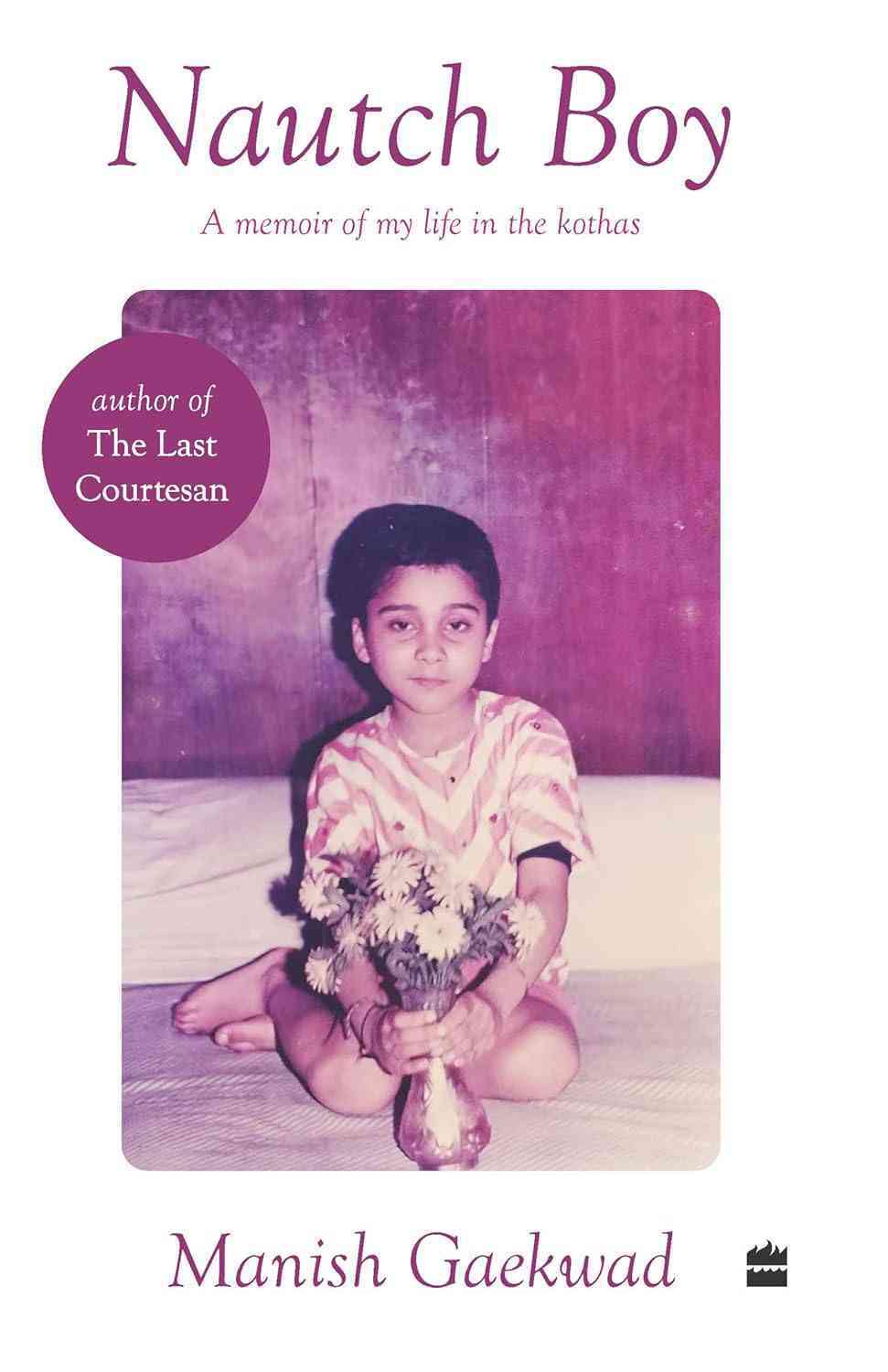

A woman in labour, caught between life and death, chooses her own survival over the unborn child. Manish Gaekwad’s Nautch Boy: A Memoir of My Life in the Kothas opens not in the comfort of nostalgia but in the rawness of a difficult yet pragmatic choice. The woman’s decision does not render her a callous, selfish, or cruel mother; it reveals a different kind of love, connection, and agency too. Rekha Bai, the mother, a courtesan, does not want her child condemned to a slow, daily death. Having pre-empted the fate usually reserved for the son of a kothewali, where the weight of stigma can suffocate long before life begins, Rekha Bai grants absolute liberation to the unborn.

The twist: both the mother and child live.

Nautch Boy moves like a slow unveiling: of memory, ignominy, love, laughter, tragedy, and pathos, all woven by poetry, artistry, music, and surely dance. A memoir of not only the son of a tawaif, nor confined to a checkered childhood navigating between kothas and classrooms; the nautch boy of this story reclaims voice and space; insists on and persists in the dignity and integrity inherent in lives many prefer to skirt past. As a teller of his own story, Gaekwad builds on The Last Courtesan, taking us deeper – not only into his mother’s world, but into his, with all its longing, confusion, ache, bruises, and warts.

Between worlds

If The Last Courtesan is a testament to Rekha Bai’s journey through the lens of her son, this book turns the gaze inward. It is Gaekwad writing himself into being – the child who was raised in a kotha in Bombay, who went on walks with his mother and rode horses at Chowpatty, grew up around an absent mother who “sang for the world, but not a single lullaby for me”, who overheard his mother telling someone on the phone, “Pata nahi kyon aaya hai, muft ki roti todh raha hai (Don’t know why he is here, breaking free bread)”, the son who struggled with the knowledge that his mother’s profession was not one to be worn as a badge of honour; and the young queer man traversing a society that had no language, no acceptance or tolerance for his desires. Moments of humiliation, dejection, or dissatisfaction, however fleeting, shape something inside him, adding layers to his character arc.

There is helplessness, seething rage, and confusion, but there is also empathy and unbridled sensitivity. He resists being defined by what others think he is: “just like his mother” or “a boy who danced”. Being the son of a tawaif somehow gave license for “effeminate” behaviour, for mimicry, for failing to conform to masculine norms. Such remarks and gender stereotypes are not dismissed with bitterness, but held. Examined. Borne. He is mocked, overlooked, neglected, and misunderstood. But he is also gentle: to his mother, to art, to beauty.

Gaekwad writes with a tenderness sharpened by honesty. The opening chapters move through fragrances, musical notes, and voices: the mujras, the perfumes, the rhythm of laughter and sorrow, all folded together. Rekha is neither mythologised nor demonised; the son presents her as she was – cultured, astute, proud, flawed, and fiercely resolute. A courtesan in Calcutta’s Bowbazar in the 1980s, Rekha Bai was known as “Kalkatta ki mashoor dancer”. She lived in a lane called Bandook Gully (Gun Lane), and knives were polished at the entrance of the kotha where there was no sign of books or literature. From this realm of hedonism surfaces someone who would go on to wax eloquent on Kafka, Marquez, and Maugham.

Rekha wants more for him – her son must thrive and not merely survive. The decision to send him to an English boarding school in Darjeeling, despite meagre resources, was both a maternal sacrifice and a radical strategy. The boarding school for his safety and better education, the English-speaking lessons, the insistence that Monty (Gaekwad) learn literature, music, classical subjects – create a universe in which the mother does not seek “escape,” or “refuge” as society might label it, but she protects or safeguards her son from the terrain of pimps, invisible labour, and of dishonour born of assumption.

A central achievement of Nautch Boy is its careful distinction – and its insistence – between kotha as an institution of artistry and patronage, and the world of brothels, strip clubs, dance bars, where performance is for commodification. A tawaif, the author reminds us, is not a sex worker. Rekha is the epitome of nazakat, coquetry, elegance, shokhii, playfulness, aesthetic training, and etiquette. Her consent mattered; her art was her calling card. Gaekwad, once an entertainment reporter at Scroll, shows how that tradition is slowly put under pressure: how shifts in culture, economics, and morality corroded those codes; how what was once nurtured as art becomes misunderstood, denigrated, and even erased. In the 1990s, patrons began visiting kothas only for sex as the mujra had stopped. A culture was on its deathbed.

At the other end, the austerity of the 1980s offered little space for queer self-recognition. Gaekwad, labelled “chhakka”, “naazuk”, writes with disarming candour about the confusion, the mockery, the loneliness. Yet what emerges isn’t a plea for sympathy but a declaration of survival. His sexuality was never given credence, but in retrospect, it forms an essential part of how he understands himself.

In more ways than one, this memoir is a social document. Radical changes in Indian urban life, class mobility (or lack thereof), the politics of respectability, the pressures on gender and sexual identity – all appear not as academic points but as lived, daily, intimate realities. How the kotha behaves as a liminal space: half hidden, half exposed; how those inside it may claim dignity even as outsiders deem it abominable. Gaekwad refrains from romanticising the kotha; he describes its poverty, compromises, compulsions, and dangers. But he is clear: there was, is, something precious there. The kotha is both refuge and prison, nurturing and damaging: a duality that lends the book its force. Gaekwad refuses simplistic binaries. He honours the art while confronting the exploitation; he cherishes his mother’s courage while acknowledging the toll her choices took on their relationship.

Cathartic release

What gives the memoir its power is not just what Gaekwad writes, but how. His prose is spare at moments, lush at others. He pauses on small things: the feel of fabric, the scent of powder, the touch of discarded books, the echo of a song, the texture of his mother’s shrill voice as opposed to the soothing timbre of Bollywood playback singer Kavita Krishnamurthy. His writing flows between anecdote and reflection, allowing moments of intimacy to open into commentary on society and culture.

His memories – of cramped chawls of Bhat Nagar in Poona, of schooldays in Darjeeling, of moments of estrangement and reconciliation with his mother – are offered without embellishment, as though he is clearing space inside himself. At times, the transitions between cities – Calcutta, Bombay, Poona – feel compressed, with secondary figures fading rather quickly. But this brevity also reflects the memoir’s focus. The central relationship, between mother and son, commands the stage. Everything else is a backdrop. He allows humour – sometimes dark, at times absurd – to puncture the sorrow and despair. These moments of levity sharpen the pain; they make the human condition more bearable.

And there is catharsis. Gaekwad seems to need this book more for himself than for his readers – to exhume things buried, name unsaid things and feelings. A coming-of-age story, yes; a queer coming of age; a son’s coming to terms with his mother’s life; and, finally, an ode to the woman because of whom he exists.

Reading Nautch Boy is to confront the ways society draws lines: between “desirable” and “shameful,” between public morality and private artistry; the often-unspoken punishments meted out to those who live on the margins not out of choice but by design. In recording the events of his life, Gaekwad holds up a mirror to readers: what do we assume? What do we refuse to see? Stories like Gaekwad’s are seldom told in their fullness – and rendered with such courage. The book lingers because it refuses to let readers off the hook. It unsettles, moves, and finally affirms.

It is a memoir without illusions – but one suffused with love. For readers of The Last Courtesan, it is a response and an affirmation. For those new to this world, it is an invitation: to listen, to unlearn, to feel. It is an unmissable portrait of lives we too often turn away from. And for Indian literature, it is a rare work: a memoir that insists that love, art, and dignity can survive even amid the harshest circumstances, with the most modest means.

Nautch Boy: A Memoir of My Life in the Kothas, Manish Gaekwad, HarperCollins India.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting