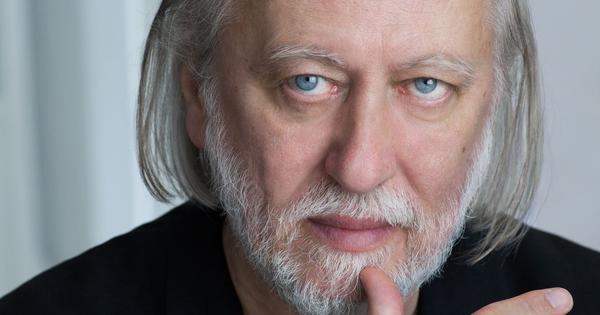

László Krasznahorkai. My first introduction to his work was through the films of the Hungarian auteur Béla Tarr. Needless to say, the connection is Sátántangó’, Tarr’s seven-hour and 19-minute epic. Although Sátántangó was released in 1994, I had the opportunity to see the film two years later, in 2000. Around the same time, I watched Tarr’s Damnation, originally released in 1988. All this in during the pre-streaming era, and I distinctly remember the film club congregation where these films were screened as an introduction to the brave new world of post-communist East European World Cinema.

On the title card of the films, I noticed this Krasznahorkai’s name as a collaborator on the screenplay, along with Tarr. After digging a bit, I found out that while the original script for Damnation was written for the film, the source for Sátántangó was Krasznahorkai’s novel, which was already considered a classic in Hungary. However, back then I couldn’t locate an English translation of Sátántangó.

Cut to 2001. A Barnes and Noble bookstore in Seattle. I came across the name again. A sudden, unexpected, serendipitous contact – perhaps this is how excavation of memory is accomplished! However, the novel on which the name was inscribed had a different name – The Melancholy of Resistance.

Tragic myths

I can be classified as a “fast reader”, but surprisingly, I couldn’t finish this novel very quickly. At first glance, the plot is minimalist. A mysterious travelling group, consisting of several people, appears in a small Hungarian village, pulling a huge cart, promising an extraordinary sighting of the “biggest whale in the world”. But instead of joy and wonder, the newcomers, whose mastermind calls himself “The Prince”, attract a group of outsiders who are mysteriously ready to unleash violence.

For some time the village falls into complete chaos until the army finally enters and an uneasy peace returns. In Krasznahorkai’s claustrophobic universe, there is no law or order, and the state hardly matters. Human progress is a tragic myth, life is an icy museum of meaningless existence, and knowledge seems to lead only to loathsome illusions or irrational despair.

The plot of the story may be skeletal, but Krasznahorkai’s style seemed quite difficult at first glance. The entire novel is composed of extremely long and dense sentences, lacking paragraph breaks. There is a strange philosophical tension within this tightly woven style – the long sentences act like multi-faceted lenses that reflect the world from multiple perspectives almost simultaneously, while this density simultaneously resists my “fast” reading. The Hungarian city in the novel is marked for pessimism and anarchy. Education and bureaucracy have collapsed, there is no coal to heat homes, telephone lines are broken, and bus and car travel are impossible.

The conclusion of the story is, of course, quite introspective. Amidst the chaos and darkness, what remains is the dead and rotting whale – which perhaps signals a psychological, social, natural, or even a divine “fall”. However, the mere fact and presence of such an amazing creature leave a miraculous streak of magic whose ripples continue for a long time.

Then came a long wait – in 2006, the author Krasznahorkai emerged again in my reading universe after the publication of another translated novel, War and War. Bureaucratic archivist Korin discovers a manuscript that cannot be immediately classified. He realises that the manuscript is a wondrous, foundation-shaking work of a cosmic genius and decides that he has to dedicate his life to immortalising this lost, obscure manuscript. To accomplish this task, he travels to New York, meets some unpleasant characters, and buys a computer and a website space to post the manuscript. The simple yet complex plot of War and War quickly gets buried under Krasznahorkai’s frenetic pinball prose. Towards the end of the book, Korin reflects on the extraordinary use of language in the manuscript – a cryptic meta reference to Krasznahorkai’s own writing style:

“…this enormous sentence comes along and starts to egg itself seeking ever more precision, ever more sensitivity, and in so doing it sets out a complete catalogue of the capabilities of language, all that language can do and all it can’t, and the words begin to fill the sentences, leaping over each other, piling up, but not as in some common road accident to be catapulted all over the place, but in a kind of jigsaw puzzle whose completion is of paramount importance, dense, concentrated, enclosed, a suffocating airless throng of pieces…”

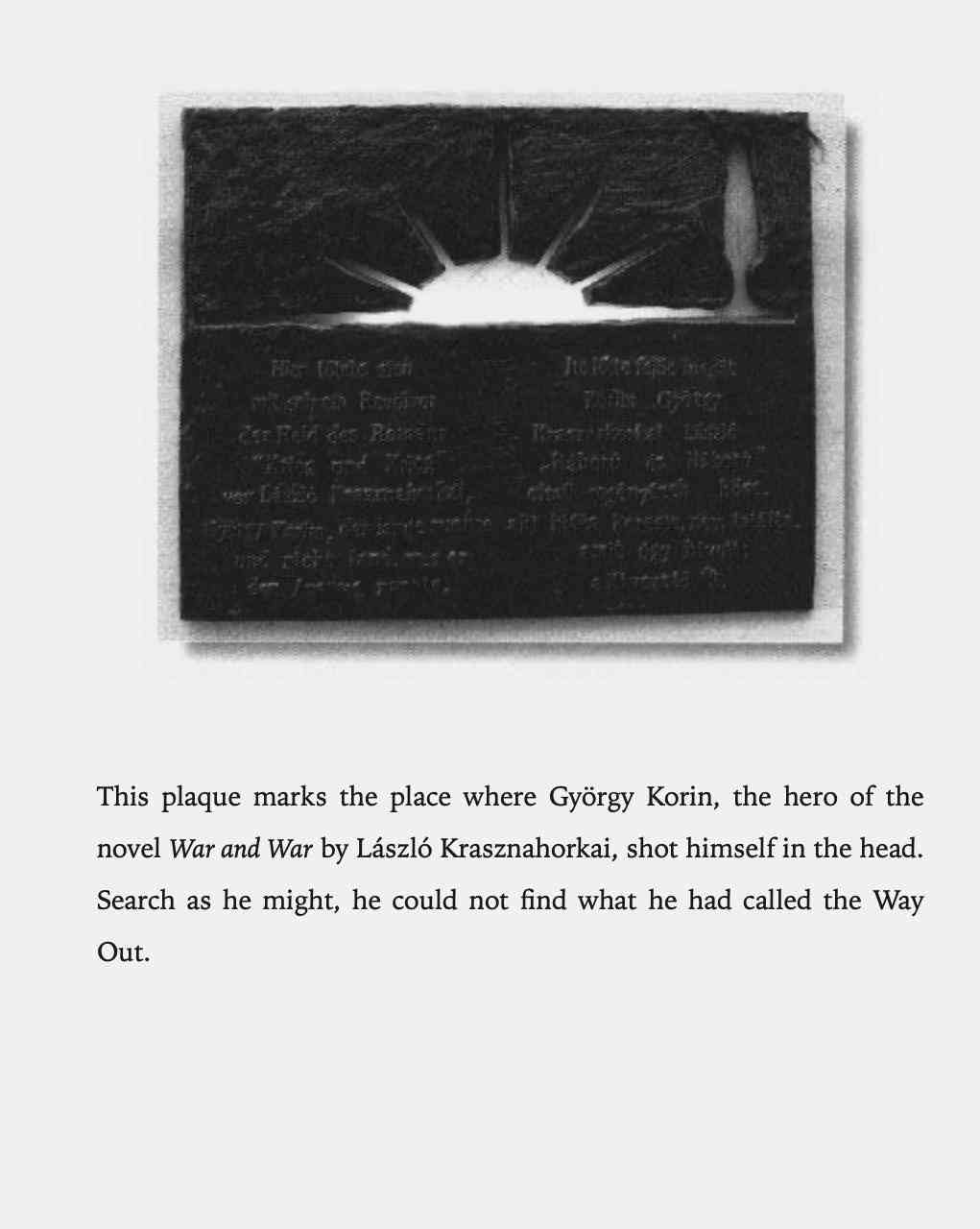

The manuscript is unique. We only hear about it through Korin’s description, but it is a strange object. At the heart of the narrative within the manuscript are four obscure travellers, who wander through various historical times and places, from Greece to Italy and Africa, usually just before some kind of disaster or war. At the end of the book, there is an embedded image of a plaque commemorating the suicide of György Korin. The sentence below the image is very significant – “Search as he might, he could not find what he called the Way Out.”

Sátántangó was translated 27 years after it was published in Hungary. The film adaptation had already mesmerised the audience all over. However, since a film has a different visual idiom, the enthusiasm for reading the words in the book is not entirely similar. The book, about 270 pages long, has no paragraphs and is divided into 12 chapters. The first six chapters describe a small Hungarian village. Once an industrial town, the factory that served the village has long since closed, and now only a few residents remain. They exist in a slum of mud, spiders, and decay. The landscape has a kind of post-apocalyptic feel, both physically and mentally. Local teenage girls sell themselves in abandoned factories, but the number of customers is meagre. The local doctor is only concerned with his own illnesses and his relentless inventorying of the habits of other villagers. It is a place where these aimless residents are neighbours, but they are essentially alone.

Suddenly, rumours reach the village of the return of two people, long thought dead: Irimiás and Petrina. Apparently, Irimias is seen as a saviour, as his arrival may usher in an opportunity for renewal and redemption. The first six chapters of the novel are numbered, I to VI, building up to the arrival of Irimias and Petrina, and the remaining six chapters are reversed, VI to I, much like the repetition of the steps of a tango dance. The translator, George Szirtes, aptly summed up the significance of the title, “At the centre of Sátántangó is the eponymous drunken dance, referred to here sometimes as a tango and sometimes as a csardas. It takes place at the local inn where everyone is drunk … Their world is rough and ready, lost somewhere between the comic and tragic, in one small insignificant corner of the cosmos. Theirs is the dance of death.”

It is later revealed that Irimiás and Petrina may be suspicious adventurers and impostors – low-level, undercover, renegade state security officers. Irimiás may be the “Satan”, yet there is no real evidence in the pages of the novel that he has any importance beyond what the villagers think about him. The book’s language and narrative directly address the problem of the existence of a universe without meaning and ultimate authority. But nowhere in the book does the author give a specific answer, because there is no definitive answer to any cosmic question.

While the ghosts of feudalism and moribund communism haunt the characters of Sátántangó, Krasznahorkai is interested not only in the Hungarian psyche under a failed socio-political system, but also – perhaps more – in the perspectives and confusions we try to create in order to forget the illness and despair that ails the human spirit within all systems.

Motion in every aspect of life

After Krasznahorkai won the International Man Booker Prize in 2015, a slew of translations came out – Seiobo There Below, The Last Wolf and Herman, The World Goes On, Chasing Homer, Herst 07769, Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming and others. But since I read all his works in translation, it is worth praising the translators, especially George Szirtes, who is also an accomplished poet. New readers can start with Seiobo There Below. The 17 chapters are numbered according to the Fibonacci sequence, beginning with 1 and ending with 2584. Each chapter is independent of the other; the time and setting are constantly changing but still converging on the idea of art and beauty.

I do not presume to evaluate Krasznahorkai’s entire literary oeuvre. I can only repeat what the American critic Susan Sontag said about him – “the master of apocalypse”. The statement of the Swedish Academy concurs, “László Krasznahorkai is a great epic writer in the central European tradition that extends through Kafka to Thomas Bernhard, and is characterised by absurdism and grotesque excess… But there are more strings to his bow, and he also looks to the East (in A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East and Seiobo There Below the main foundations rest on Chinese and Japanese philosophy) in adopting a more contemplative, finely calibrated tone.”

But what do I find in Krasznahorkai’s writings that draws me back to his writings like a magnet? French philosopher Paul Virilio spoke of a concept called “dromology” – the ubiquitous, pervasive inscription of motion in every aspect of life. The point is that dromology is the study of motion and its impact on modern society. Virilio argued that the increasing speed of technology – especially in transportation and communication – is fundamentally changing human concepts, social relationships, and political structures. Virilio coined the term “dromocratic society” to describe a society organised around the logic of motion, where motion determines the distribution of power and wealth. An irrefutable truth, which we see around us every moment.

Krasznahorkai’s writing, subsequent iterations, and the persistence of the fundamental proposition of withdrawal mark a silent resistance to this incessant need for motion or dynamism. His writing style is a conscious rebellion against the culture of instant gratification. That’s why long sentences cannot be rushed through; one has to take their time and meditate on their density. He wants us to linger on the calibrated flow of the words as it uncoils itself in slow motion.

Even in a novella like Chasing Homer, shaped like a chase thriller, the ceaseless pursuit (an unnamed narrator pursued by unnamed assassins for reasons not known) becomes less of an escape across Europe than a condition of existence. The narrator states: “I’m a prisoner of the instant…an instant that has no continuation.” In a novel where velocity is the marker of the narrative, frenetic pace amounts to a strange sense of stasis where the narrator “has no time between two instants. Since there’s no such thing as two instants.”

Critics are divided on whether Krasznahorkai’s writing resembles the controlled surplus of Thomas Bernhard or the aesthetic excess of José Lezama Lima. After reading this novel several times, I feel that its pace is consciously restricted by its chaotic yet ponderous interiority. The characters create and exhaust meaning in the interludes, and from within that, a mysterious, elusive sense of contingency reigns. At least for me, his writing takes a detour from The Melancholy of Resistance towards a “melancholy of sloth” in a society that is otherwise driven by the need for constant motion.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting