Bangladesh has seen many uprisings and military coups leading to the abrupt fall of a government. However, never in the country’s history did the governor and other senior officials of the central bank flee after a political change.

Even on December 17, 1971, senior-most Bangladeshi officials of the erstwhile Dhaka office of the State Bank of Pakistan walked across the road to the Mukti Bahini and Indian army camps in the stadium and reported to duty. Not so on August 6, 2024, when the Bangladesh Bank was left without a governor.

This illustrates the near catastrophe that was the economy 12 months ago. Judged against that starting point, the Interim Government has managed the economy well in the past year. However, for all the talk of reforms, Bangladesh 2.0, a new political beginning and so on, this has been an interim economy. That is, if you were expecting reforms, you would be sorely disappointed.

Let’s recall the immediate economic challenges the Interim Government faced as it took office last August.

Firstly, inflation was already at its highest in decades even before the economic disruptions caused by the uprising and then the floods in August. Meanwhile, the central bank’s stock of foreign reserves were depleting and the taka had been depreciating for the previous couple of years. And again, that was before the effects of remittance boycott from expatriate Bangladeshis during the July uprising was felt. Finally, the country’s banking system was near collapse.

Incidentally, the central bank governor was a key functionary in the Sheikh Hasina regime’s criminal mismanagement of the economy, directly contributing to the three immediate challenges the Interim Government faced. No wonder he and his senior officials fled.

The banking sector woes, inflation, and the external sector pressures were all interlinked. Like many developing countries, Bangladesh faced high import prices in 2022. Instead of allowing the taka to depreciate in an orderly manner and slowing import demands by raising interest rates, the Hasina regime embarked on a mix of policy steps that the International Monetary Fund generously called “eclectic”.

Interest rates were capped below inflation, which meant money was cheaper-than-free for the regime cronies. They borrowed heavily from banks that were under their control, and siphoned the money abroad. This put further pressure on the taka. The central bank tried parallel exchange rates, and the government tried to curb imports through administrative controls. Unsurprisingly, this 1970s-style farrago failed – reserves kept bleeding, taka kept sinking, and prices kept going up.

As soon as he assumed office, the new Governor of the Bangladesh Bank set about stabilising the banking sector. The task was monumental. There was a non-trivial probability 12 months ago that we would see riots in front of banks. The fact that a run on the banking sector, or even any individual bank, has been avoided is a success. However, the longer-term structural reforms of the banking sector – that task has barely begun.

The new governor has also pursued what one might call textbook policies to stem inflation and stabilise the external sector – raise policy rates and hold it high until inflation comes down and the reserves stop depleting before gradually leaving the exchange rates to the market forces.

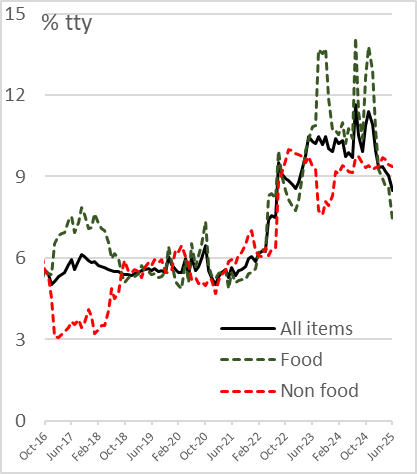

As Chart 1 shows, interest rates have risen, while Chart 2 shows that inflation is already declining. The sensible monetary policy was assisted by a bit of luck in the form of a bumper winter crop, and astute supply chain management by the Interim Administration during the Ramadan and other peak demand episodes.

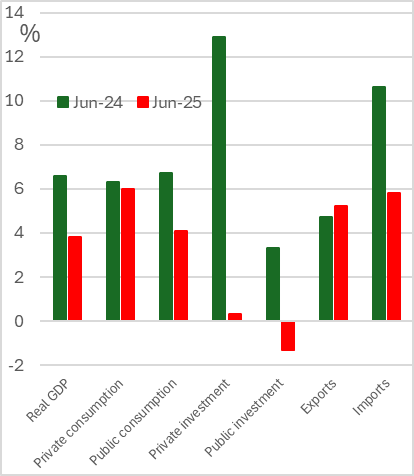

The stabilisation of the external sector, of course, partly reflects slowing import demand, which has been partly offset by higher remittances. The combination of weak imports and strong remittances are also evident in the national accounts data. Chart 3 compares the International Monetary Fund forecasts for the 2024-’25 fiscal year published in June 2024, just before the Monsoon Revolution, with its estimates for the year that was published in June 2025.

Thanks to strong remittances flow, private consumption grew broadly in line with the forecast. However, private investment barely changed, compared with a strong growth forecast a year ago, reflecting the higher interest rates as well as the political uncertainty. Public demand was also weaker in the fiscal year, reflecting a fiscal tightening by the Interim Government. Weaker investment and public demand meant not just weaker imports, but also a significant slowdown in growth compared with what was expected in June 2024.

Back in June 2024, the International Monetary Fund was expecting the economy to grow by 6.6% in the financial year 2025. Its latest estimate is that the economy grew by 3.8% in the last fiscal year. This growth slowdown reflects not just the economic disruptions and uncertainty caused by the Monsoon Revolution and the aftermath, but also the tighter policy settings needed to bring down inflation and stabilise the external sector. The slowdown was the bitter medicine we had to swallow.

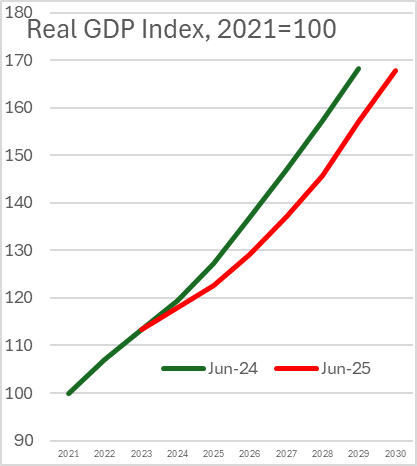

However, the shock is also leaving a scar, as shown in Chart 4, which compares the size of the economy over the rest of the decade in the two vintages of the International Monetary Fund forecasts. In June 2024, the economy was expected to be 68% bigger than the 2020-’21 level by 2028-’29. The same level is now reached one year later in the latest forecast. That is, according to the International Monetary Fund, the disruptions of the past year will cost us around one year of the gross domestic product by the end of the decade.

And we have seen absolutely nothing from the Interim Government about how this long-term scarring can be healed. For all the talk about reforms, as far as the economy is concerned, Professor Yunus and his cabinet have behaved explicitly like an interim, transitory, short-term administration. How do we make up for the past losses? That is something for the elected government to figure out.

This article was first published on Counterpoint.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting