India’s “pushback” policy, under which alleged Bangladeshis and foreign nationals are being forced out of India’s borders, is a procedurally flawed, opaque and onerous legal process that reflects the fraught terrain of Indian citizenship and belonging.

Since May, the police, primarily in Bharatiya Janata Party-ruled states, have been rounding up people they suspect are Bangladeshi or foreign nationals for entering or staying in India unlawfully.

But instead of adequately investigating citizenship status of those detained or conducting criminal trials, the police and border forces are conducting state-led inquiries followed by outright deportation: those detained are forced out of India, usually into Bangladesh.

The journey from citizens who may be migrants in other parts of India to “illegal immigrant” is astonishingly short, with little to no legal recourse.

In this way, the “pushback” policy has become an alternative process, with little oversight and safeguards, which risks creating stateless individuals while placing the burden on marginalised groups to prove Indian citizenship.

Such an arbitrary process violates the constitutional and legal protection of Indian citizenship and the constitutional guarantees of a fair process, which exist for foreigners as well.

What is the law?

Migration, entry and exit, and deportation through Indian borders are governed by The Foreigners Act, 1946, The Passports Act 1967, Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939, The Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920, The Citizenship Act, 1955, and the Repatriation of Prisoners Act, 2003.

The Immigration and Foreigners Act of 2025, which was passed by Parliament in April and received presidential assent, seeks to consolidate some of these legislations.

Under the Foreigners Act of 1946, the Ministry of Home Affairs in 2009, and from time to time after that, prescribed the procedure to deport Bangladeshi and other foreign nationals detained in India.

Previously, if alleged Bangladeshi nationals were detained and prosecuted under the Foreigners Act for illegal entry and stay in India, the case would be referred to the Bangladesh High Commission to verify the person’s nationality, after which they would be deported.

But a directive reported to have been issued by the home ministry on May 2, 2025, under which the current detentions and “pushback” are being carried out, lays down a slightly different procedure. One notable omission is that the process no longer requires verifying nationality with Bangladesh or another country.

The order does not appear to be available online, contrary to the basic legal norm that rules should be published and accessible. It empowers the state governments and the union territory administrations where the suspected foreigners are found to be living “illegally” to conduct an inquiry.

If the alleged foreigners claim Indian citizenship, state authorities must verify their nationality by obtaining a report from the local officials of the state or district where the person claims to hail from. This process must be completed in 30 days, during which time the person will be kept in a detention centre.

Rafikul Biswas, a school bus driver in Bengaluru, was picked up by the Karnataka Police on suspicion of being an undocumented Bangladeshi migrant – even though he had submitted his Indian passport as proof of citizenship.

Anant Gupta reports: https://t.co/HjK0MVxpfo pic.twitter.com/tBq0nKMAij

— Scroll.in (@scroll_in) September 2, 2025

Suspicion implemented through law

There are several problems with this process.

First, the starting point is mere suspicion on the part of the police or the law enforcement agencies that a person is a Bangladeshi or Myanmar national who has crossed into India illegally. This suspicion is founded on a mix of prejudices and stereotypes of class, religion, language and ethnicity. Poor, Bengali-speaking Muslims are most at risk.

Second, the process of determining whether someone is an Indian citizen or a foreigner who entered India illegally is an entirely internal, state-led enquiry. It is not carried out before any court.

If no verification report is submitted within 30 days by the local authorities of the Indian district where the alleged foreigner claims to hail from, then the person is presumed to be an illegal immigrant and can be deported.

This problematic reversal of the burden of proof originates in Section 9 of the Foreigners Act 1946, which is also carried forward in the 2025 Act. It states that wherever a question arises under the Act about whether a person is a foreigner, it is presumed that they are a foreigner. The burden of proving otherwise is on the suspected person.

This is at odds with the presumption of the continuance of citizenship under Article 10 in Part II of the Constitution, which outlines the provisions of Indian citizenship. Article 10 says that anyone deemed to be an Indian citizen under the provisions of Part II and subject to laws made by Parliament continues to be an Indian citizen.

Third, the order presumes that records of birth, education, residence, land-holding, employment and the like that prove Indian citizenship and residence claims are readily available with local authorities and can be obtained quickly.

This is completely removed from reality.

Some of the current battles over citizenship have reached the courts, but what we hear is not encouraging because the very documents that people are frantically trying to collect may be of limited or no use.https://t.co/RMgEiJx2gq @samar11 ✍️ pic.twitter.com/lvAEtuL3jK

— Scroll.in (@scroll_in) August 23, 2025

Experience shows that accurate documentation is especially difficult for women, the elderly, and children born while their parents are working in a different city.

There is also no single document that conclusively proves Indian citizenship, except the passport, which few Indians have – a report in The Times of India, based on data from the Ministry of External Affairs, estimated that only 7.2% Indians had passports.

Instead, proving citizenship involves producing various documents to show that one is a citizen by birth, descent, naturalisation or registration under the Citizenship Act, 1955.

As the special intensive revision of electoral rolls in Bihar shows, most identity documents available with ordinary people – whether they are immigrants or citizens – are not proof of citizenship. Similarly, the Bombay High Court said in August that documents such as Aadhaar, voter ID and PAN are not proof of Indian citizenship.

Fourth, the consequences of verification not being conducted in the 30-day time period are drastic. A suspect can be quickly declared a non-citizen. If a foreign country does not accept a person who is being forced out, they are at the risk of being rendered stateless.

It also means that Indian citizens who are not able to prove their legality to the satisfaction of the authorities risk being detained and forced out of India’s borders, sometimes even despite having submitted their documents.

An Indian citizen by birth or descent cannot be deprived of citizenship, even under the Citizenship Act 1955. But this verification process becomes an arbitrary way of potentially stripping Indians of their citizenship, beyond the scope of the Foreigners Act, and contrary to the Citizenship Act and the constitutional protections in Article 10.

Fifth, the home ministry order does not provide the suspected foreigner with an opportunity to present their case, provide documents and evidence, rebut the findings in the reports submitted by the local authorities and explain inconsistencies.

Verification appears to be solely based on the report received from the local authorities in the area the alleged foreigners claim residence of, and the inquiry conducted by the state where the person is found.

There is no explanation of what the inquiry entails and neither is there any requirement that the person in detention be provided a copy of the verification report or its findings.

The process is opaque by design.

In the absence of procedural safeguards, the presumption of foreignness is even more dangerous. The entire process contravenes the promise under Article 21 of the Constitution, available equally to non-nationals, that a process curtailing liberty should be just, fair and reasonable.

Those detained are charged with offences under the Foreigners Act 1946 and other statutes. But no criminal trial is conducted pursuant to these charges, with the attendant requirement for proving a criminal offence beyond reasonable doubt.

A summary, underdefined, state-led inquiry is treated as definitive, instead of the state having to prove the offence, imprison and then repatriate or deport.

Finally, once the state authority finds that a person is an undocumented immigrant and orders their deportation, there is little legal recourse left except to move constitutional courts by way of writs – assuming that the detained person’s family is able secure legal representation. The home ministry order does not provide details of an appellate authority that could be approached.

Other troubling consequences flowing from the introduction of biometric registration in the May 2025 order have also been flagged.

The deport-first, ask-questions-later policy helps the state avoid several inconveniences: it does not have to house detainees for long or create detention facilities and nor does it have to prove criminal charges under the Foreigners Act to a higher standard.

In the past, courts have ordered release of detainees, on certain conditions, in instances of prolonged detention. This is not a palatable option for the state from a security perspective. With direct removal, the state also sidesteps accountability for the treatment of foreign detainees and refugees under international law and norms.

Some are more citizen than others

States exist for the wellbeing of their citizens and are justified in protecting their territory and controlling their membership.

But that only emphasises the importance of citizenship as a political status in the modern world: citizenship is not just the right to have rights, but is a right in itself. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to a nationality and not to be arbitrarily deprived of it.

Therefore, any process that declares someone a non-citizen or removes them from the territory of a country must adhere to procedural justice and non-arbitrariness.

The Indian government’s “pushback” policy fails on these counts. Many of these problems are not new, but the latest version of the process and its manner of implementation is certainly more concerning.

What is also troubling is that the Supreme Court has struck an apathetic note by denying interim relief while hearing pleas opposing the “pushback” policy.

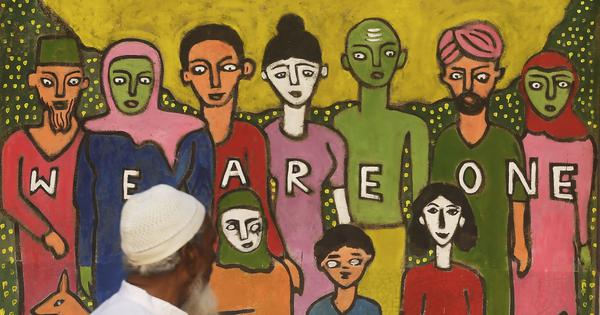

The pushback exercise and the judiciary’s response lay bare ideas of who counts as firmly “us” and who is seen as expendable and can be made hostage to arbitrary processes, regardless of whether they are citizens in law.

Mansvini Jain is an advocate practicing in Delhi.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting