By Sanjay Raman Sinha

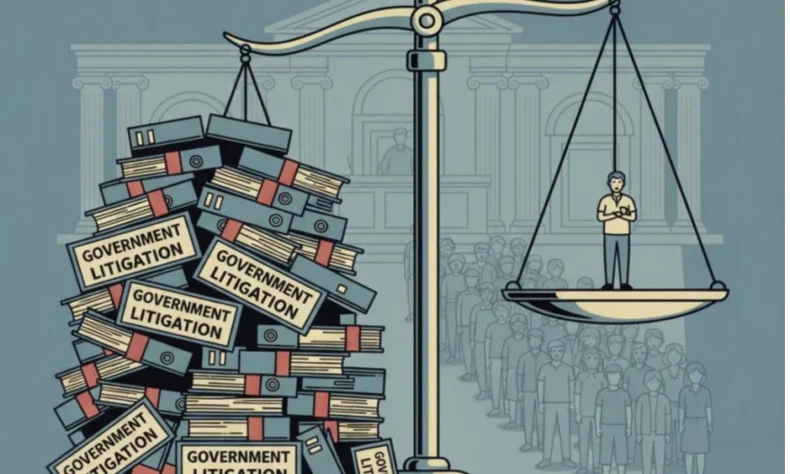

A recent remark by Justice BV Nagarathna has reignited the debate over the government’s role as the nation’s largest litigant. She sharply criticized government agencies for pursuing cases with slim chances of success—cases that not only drain public money, but also waste valuable judicial time. In the same breath, she called for wider adoption of mediation as a tool for quicker, less adversarial resolution.

The numbers tell a troubling story. Government litigation makes up nearly 50 percent of all pending cases in Indian courts. In the last decade, the centre has spent over Rs 400 crore on court cases, with Rs 66 crore in legal costs in 2023-24 alone. Pending government cases have surged from 4.11 lakh in 2019 to 7.32 lakh today. The Ministry of Law recently informed parliament that the Union government is a party in almost seven lakh pending cases—with the Finance Ministry alone entangled in nearly two lakh.

These staggering figures highlight a systemic problem: while the government champions faster justice and alternate dispute resolution on paper, its own litigation practices continue to choke the judicial pipeline.

THE MACHINERY BEHIND THE LOGJAM

The culture of government litigation is often mechanical. Departments launch and pursue cases without serious consideration of judicial precedents or expert legal opinion. Litigation is valued for its procedural worth rather than its merit, leading to poorly thought-out strategies that drag on for years. For bureaucrats, litigation is just another routine task, not a mission to resolve disputes fairly or efficiently.

This issue isn’t new. As early as 1973, in Dilbagh Rai vs Union of India, the Supreme Court warned that the absence of a litigation policy burdens both the exchequer and the judiciary. Later rulings—including Kamakshi Tradexim vs Union of India, State of Punjab vs Geeta Iron & Brass Works, and Chief Conservator of Forests vs Collector—by the apex court underlined the same theme: the government must litigate responsibly, prioritize settlements, and avoid dragging inter-departmental disputes into court.

THE NATIONAL LITIGATION POLICY: PROMISE AND PITFALLS

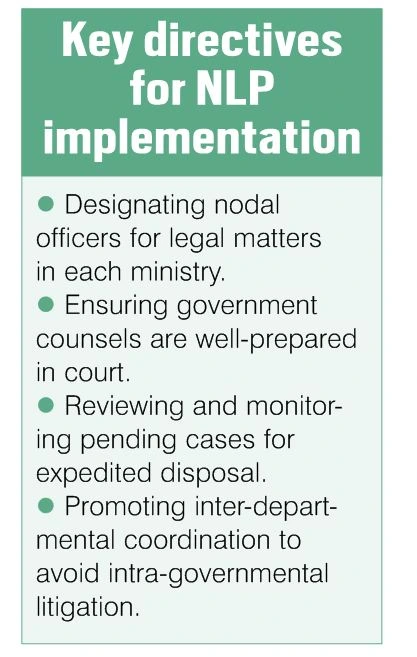

To address these concerns, the National Litigation Policy (NLP) was introduced in 2010 with the goal of reducing pendency from 15 years to three years by weeding out frivolous cases and making the government a “responsible litigant”. Successive governments have revised it, but implementation remains patchy. Bureaucratic resistance, departmental silos, and lack of accountability have kept the policy from making a real impact.

Recently, the government has even appeared to retreat. In September, the Law Ministry argued that an NLP cannot realistically be enforced since citizens are free to file cases, and the government must respond. Instead, it suggested curbing appeals, correcting contradictory orders, and using mediation for minor cases. Yet, the bigger disputes—the ones that clog the system and cost the most—continue unabated.

Unless there is political will and administrative resolve to overhaul litigation practices, the government’s reputation as India’s largest and most inefficient litigant seems destined to remain.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting