In the last two months, Jammu and Kashmir Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha has handed out jobs to several families from Kashmir whose relatives were killed by militants.

On August 5, he presided over a large event in Srinagar in which he distributed appointment letters to the next of kin of 158 men and women killed by militants. Some of the deaths took place years ago, at the peak of Kashmir’s militancy. This included civilians killed because the militants accused them of being informers, or those working for the police.

Sinha is doing what many before him, including elected chief ministers and former governors, have already done – using a 1994 policy to give jobs on compassionate grounds to the next of kin of those civilians and government employees who were killed in “militancy-related action”.

But several families say the LG administration appears to have ignored one set of victims – those killed by security forces.

“This initiative feels discriminatory,” said Bilal Ahmed Bhat, the son of Mohammad Ramzan Bhat, a shopkeeper who was allegedly tortured and killed by security forces in 1996. “This healing is only for victims of militant violence while those killed by the state are not acknowledged as victims.”

A senior journalist in Kashmir, who asked not to be identified, pointed out that the compensation policy was not selective in the past. “The state did not discriminate between the victims. The only rider was that the person killed should not have been involved in militancy-related activities.”

A lawyer at High Court of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh in Srinagar said the LG’s decisions have bred a lot of confusion. “Some families who have lost their kin in incidents where security forces were involved have been approaching me about their cases,” he told Scroll. “It’s very difficult for me to make them understand that it’s only about one side of the victims of violence.”

Scroll emailed the LG’s office, asking if there has been any change in the 1994 policy, and if civilians killed by security forces were excluded from it. The story will be updated if they respond.

Genesis of government’s aid policy

The massive violence in Kashmir in the 1990s, the initial years of a militant movement against Indian rule, led the government to draft a compensation policy for victims.

According to former bureaucrat and old Kashmir hand Wajahat Habibullah, the compensatory relief initially was only paid to Kashmiri Pandits. In 1990, under the governorship of Girish Chander Saxena, the administration decided to pay compensation to Kashmiri Muslims in case of loss of life or injury in “collateral damage”, Habibullah writes in his 2011 book My Kashmir: The Dying of the Light.

Habibullah was the divisional commissioner of Kashmir in August, 1990, when nine civilians were killed by the Border Security Force in their homes in Mashali Mohalla of Srinagar. In the book, he offers a detailed account of how he had ensured a compensation of Rs 2.5 lakh to a woman whose husband and child were among the victims.

In 1994, Governor KV Krishna Rao drafted the Jammu and Kashmir (Compassionate Appointment) Rules, 1994, which is more popularly known as the SRO-43 or Statutory Rules and Order No. 43 scheme.

This allowed compensation for victims of “militancy-related violence” and was used to offer relief to those killed by militants as well as security forces. The appointment letters handed over by Sinha were issued under this policy.

In 2014, the rules were amended to include compensation to those families of civilians who died as a result of “law and order situation” and were not found “directly involved in the actual violence.” This dealt with civilians killed in police action during demonstrations or those who died during stone-pelting incidents, though they were not involved in hurling stones.

The senior journalist pointed out that during the turbulent 1990s, many civilians killed by security forces were labelled as militants. “But when the families of those civilians protested, the government would investigate those killings and once it was established that the dead had nothing to do with the militancy, the government provided them relief under the SRO-43 scheme,” he said.

There are scores of examples like that.

Take the case of the teenager Farooq Ahmad Bhat of Srinagar’s Hyderpora area.

In 1991, Bhat was picked by some personnel of the Border Security Force from his father’s shop and allegedly subjected to enforced disappearance. After searching for him for years and seeking investigations into his whereabouts, Bhat’s family approached the now abolished Jammu and Kashmir State Human Rights Commission in 1998.

In 1999, the commission’s enquiry established that Bhat had indeed been picked up by the BSF and had died in their custody. The commission in its order in September 1999 also ordered a relief of Rs 1 lakh and a job to his family members under the SRO-43 policy. Both of these recommendations were honoured by the government.

Similarly, Ghulam Mohammad Lone of Kupwara’s Poshpora village also got a job under the SRO-43 policy after his father was killed in one of the most horrifying incidents of violence in Kashmir.

Lone’s father, Ghulam Ahmad, was among 26 civilians allegedly shot dead by the army in Pazipora village on August 10, 1990.

No acknowledgement

For years now, Mohammed Ramzan Bhat’s family has been fighting for compensation – as well as justice in a region where security forces have immunity from prosecution.

Ramzan Bhat, a shopkeeper in Srinagar’s Miskeen Bagh, was allegedly picked up by security forces from his shop in 1996. This was days after Bhat got into an argument with two police personnel over the money they allegedly owed him for groceries they had taken from the shop. He was allegedly tortured and killed.

However, the police claimed that Bhat was a militant and was killed in an encounter, a charge his family spent decades trying to disprove.

“The post-mortem conducted by the government itself clearly recorded torture marks on my father’s body,” his son Bilal Bhat claimed. “Then a CID report confirmed he was an innocent shopkeeper. These findings came from the state’s own departments. There’s even a legal opinion that states my father was a civilian who was kidnapped and murdered.” Scroll has seen the documents.

In 2007, the State Human Rights Commission recommended that Bhat’s wife, Jameela Begum, be granted Rs 1 lakh as ex-gratia compensation along with the benefits under the SRO 43 scheme “for the death of a citizen.” However, she never received either.

“Maybe if SRO relief had been given to us [by previous state governments and the current LG administration], we would not have gone through the struggle we did,” Bilal, who has a private job, said. “If the state had at least acknowledged what happened and held someone accountable, maybe we could have found some peace.”

Bilal asked why the LG’s office had not chosen his family for compensation. “Today, it seems, justice is moving in only one direction,” he said. “It feels like the system is sending a message to those in uniform: if you do something wrong, don’t worry we have got your back.”

‘Loss is loss’

The families of other Kashmiris killed by state forces raised similar questions.

“I can understand the pain of those who have lost their loved ones and the government must give them justice,” said Amir Khuroo, whose brother was killed in a fake encounter in 2011 by police in the Sopore area of North Kashmir’s Baramulla district.

But he questioned why the LG’s relief under the 1994 compensation policy excluded them. “Don’t we deserve the same treatment? Loss is loss.”

On June 29, 2011, a Class 10 student, Junaid Ahmad Khuroo, was killed under mysterious circumstances at Arampora in North Kashmir’s Sopore.

In a report submitted to the State Human Rights Commission, the police claimed that Khuroo was a militant and had opened fire on the Central Reserve Police Force’s 179 battalion and then taken shelter in a local mosque. “When he couldn’t find any escape, he shot himself with the pistol,” the report said.

Five years later, an inquiry ordered by the now abolished Jammu and Kashmir State Human Rights Commission established that the teenager had been killed in a fake encounter. “It has been found that the … Sopore police is involved … and in order to hide the gruesome murder of the deceased have fabricated a false story,” the report, prepared by a senior police official, had said.

In July 2019, the human rights commission ruled that Junaid Khuroo had been killed in custody by police and directed a compensation of Rs 5 lakh be paid to the next of his kin. The judgement also recommended registration of a first information report against the accused and an investigation by a senior police officer. It also recommended that the two accused police officers be “dissuaded” from their service.

“We waited for five years for the government to act but nothing happened,” said Amir Khuroo.

In September 2024, Khuroo approached the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh seeking implementation of the commission’s recommendations. “I went to the top officials of the government and requested them to implement the commission’s judgment.”

Nearly a year after his petition was admitted, there’s not been a single hearing in his case. “All we get is a next date for hearing,” Khuroo said.

Khurro said that since the LG, Sinha, started giving out job letters with fanfare, he had expected that his case would be considered – but to no avail.

A long struggle

For many of the families killed by security forces, the struggle is not so much about compensation – but an acknowledgement from the state of the wrong done to them.

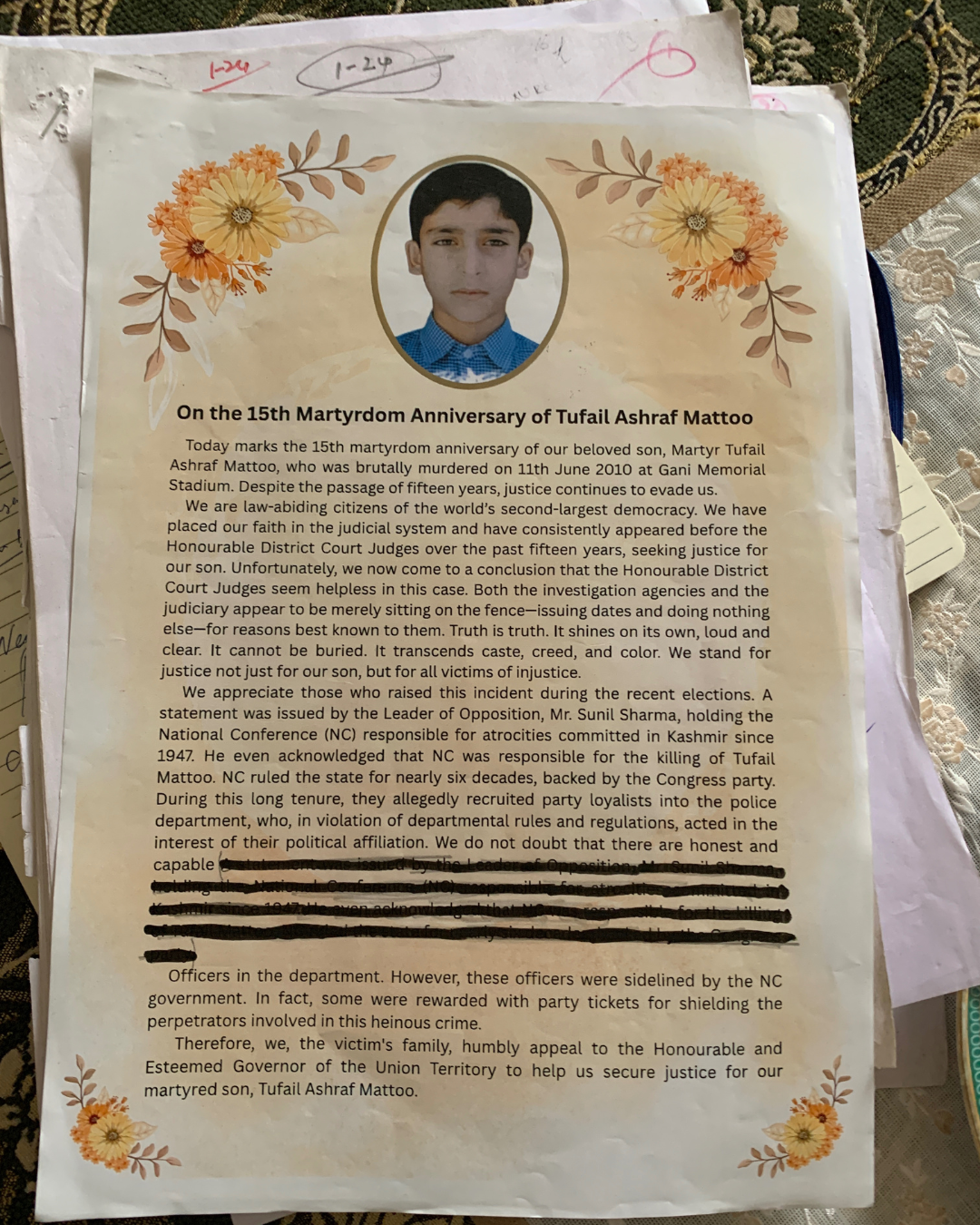

Mohammad Ashraf Mattoo is one such parent.

On June 11, 2010, Mattoo’s 17-year-old son Tufail Mattoo was allegedly killed by a teargas shell fired by the police when he was on his way home from tuitions. He was the only child of his parents.

Mattoo’s killing is considered as one of the trigger points for the 2010 summer uprising against Indian rule in Kashmir Valley. More than 110 protesters were shot dead and hundreds injured in the police action against the massive demonstrations and stone-throwing protests.

Ever since his son’s killing, Mattoo has had to struggle with even basic procedures mandated under law if a civilian is killed. For example, the first information report on his killing was registered more than a month after his death.

According to an Amnesty International brief on his case, the family went to the Jammu and Kashmir High Court in July 2011 to question the delay in the investigation.

The police filed not one but two closure reports in the case, claiming the perpetrators of the crime were ‘untraceable’.

Each time, Mattoo challenged the police’s conclusions in court. “I might have attended more than 100 hearings so far but there’s been no justice,” said Mattoo, who is in his 60s.

So, when in July, the LG directed district magistrates and police officers “to reopen” cases of individuals who had been gunned down by militants and file a first information report in cases that were “deliberately buried”, Mattoo welcomed it.

He told Scroll that the LG administration’s decision to reopen old cases of civilians killed in violence is a good opportunity to bring justice.

But he wondered if that will help families like him. “I am thinking of writing to the LG to request him to have a fresh look at my case so that a citizen of a democratic country doesn’t have to live with injustice,” said Mattoo.

“Why can’t the LG administration reopen the case and hold those in power at that time accountable, including the then chief minister, Omar Abdullah?” Mattoo asked. “After my son’s killing, more than 100 young boys were shot dead in police firing. Shouldn’t those responsible be punished?”

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting