One December evening I climbed to the mottai-madi, the bare terrace atop my parents’ four-floor apartment building in Chennai and waited for darkness to descend. The sun still hung low, an orange-red orb in the distance. Overhead, rose-ringed parakeets zipped towards their nightly roosts, squawking loudly – their day was done. Lone Indian flying foxes, fruit-eating bats, largely silent, were just setting out for their inverted day. They would glide under the cover of darkness. Alone, I waited for the nightly sky-show to begin.

In the distance, a large skeletal structure loomed – an abandoned parking garage, its insides darkened by mildew. A theatre, owned by TR Rajakumari, actor and star of the early black-and-white film era, had once stood in that spot. As a child, I watched the film Chandralekha in which Rajakumari played the village dancer who stole the hearts of both the crown prince and his lustful brother. It aired on a Sunday evening on television.

If you have seen the 1948 blockbuster – it was remade in Hindi as well, starting a trend – you will recall the beat of the spectacular drum dance near the end of the film. Maybe, you remember Ranjan, the swashbuckling villain, with his polished sneer and a menacing pair of alsatians. The lengthy swordfight between the brothers after the drum dance. The good brother, alas, was not memorable at all.

As I reminisced, celestial stars emerged on that clear night. Like the slightly mismatched eyes of a mischievous emoji, two stars winked at me from above. One was golden, the other a pale blue: Castor and Pollux, twins of the Gemini constellation, the Sky Guide app informed me.

Some of us know the twins from the logo of Gemini Studios – two bugle boys who heralded every film with the studio’s signature fanfare. Then, I remembered – Chandralekha, the hit movie, was produced by Gemini Studios of Madras. What were the odds? The twins in the sky, the former theatre below, and memory threading through both. Cinema, constellation and childhood – all aligned in one quiet Madras moment. I staggered home, a little drunk on wonder.

Growing up in Madras, I rarely looked towards the heavens. As an adult I could not recognise anything other than the moon in the night sky but thought nothing of it until I read a 2023 study in the journal Science, which said that with increasing electrification, light pollution has soared planet-wide in the last decade.

Skyglow – artificial lighting that escapes into the sky causing it to glow – now prevents humans and animals from seeing anything except the brightest celestial objects. If this present trend continues, there may be precious little left for city dwellers to see in the sky. The stars, which we ignored all along, could practically vanish from our lives.

Our blue planet is awash in artificial illumination which impacts the biological rhythms of many life forms. All living things had one universal rule – light means day, darkness means night, but it is no longer true in the age of rampant artificial lighting. Misoriented by bright lights on the beach, sea turtle hatchlings head away from the sea, and moths swarm to streetlights and their eventual doom, among other tragedies. European bats have fallen in numbers with old churches lighting up belfries for effect. Entire ecosystems are being disrupted.

Amidst all this, it seems trivial to mention that artificial light obscures the average stargazer’s view of the night skies, but this too is no small loss. Nine years ago, scientists had reported that the iconic Milky Way – home to our solar system – was hidden from one third of humanity, while the more recent study highlights the fact that things are only getting worse from the astronomer’s perspective. Before light pollution, the breathtaking view of the Milky Way had inspired artists, songwriters, and story tellers for millennia.

In his luminous essay for the New York Times, “Ask Yourself Which Books You Truly Love”, author Salman Rushdie writes: “In that impossibly ancient time, my childhood, a time before light pollution made most of the stars invisible to city dwellers, a boy in a garden in Bombay could still look up at the night sky and hear the music of the spheres and see with humble joy the thick stripe of the galaxy there. I imagined it dripping with magic nectar. Maybe if I opened my mouth, a drop might fall in and then I would be immortal, too.”

Rushdie’s garden in Bombay was under a different sky. In the 21st century, given the twin veils of light and air pollution, it could take nothing less than a complete blackout for most city dwellers to catch a glimpse of the Milky Way, but other celestial objects are still visible to the naked eye.

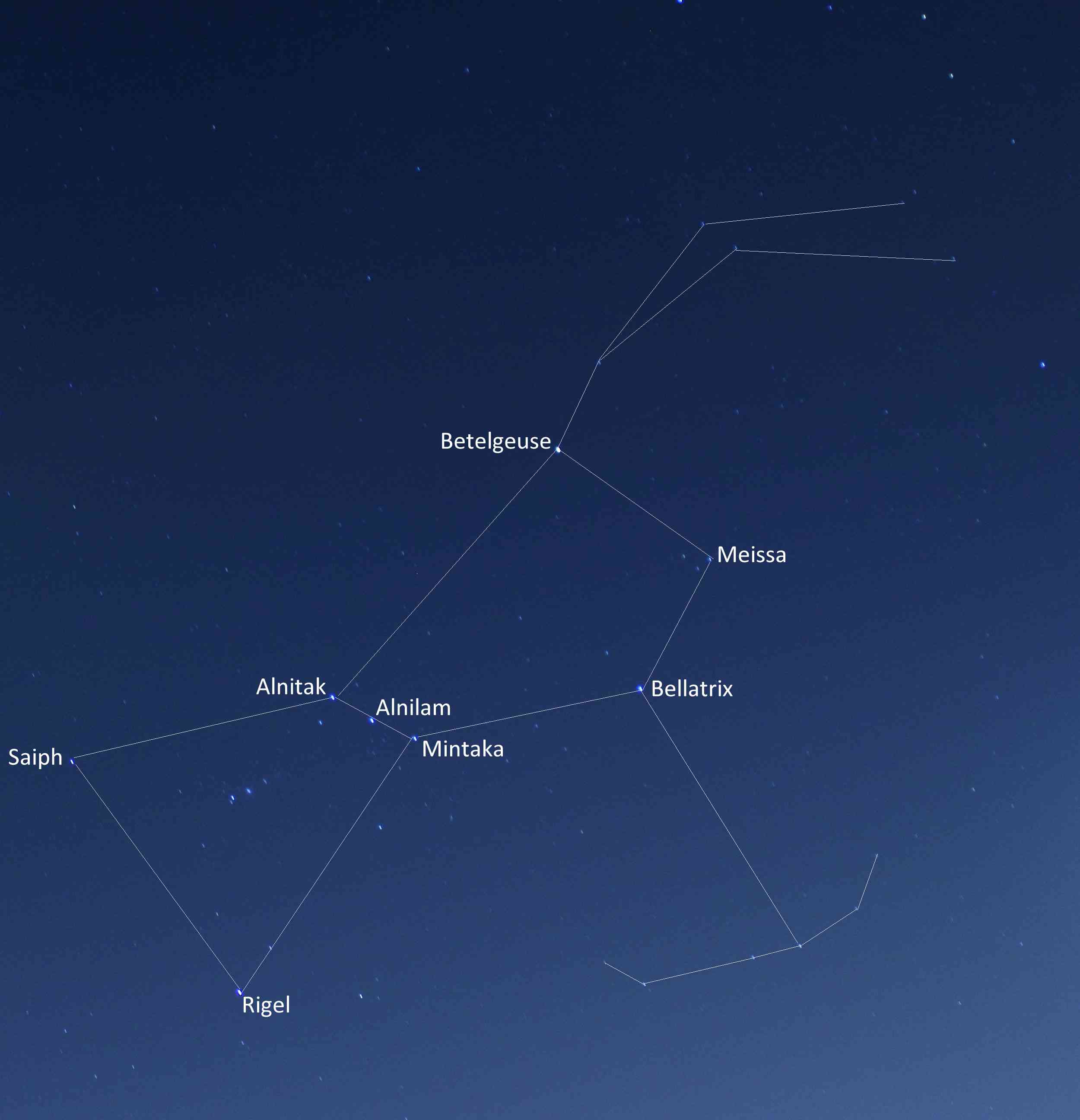

The week I saw the Gemini twins, I spotted three bluish-white stars in a row – the hunter’s belt, unmistakably Orion from Greek mythology. Since ancient times, Orion has been one of the most conspicuous constellations in the night sky. To my delight, I also see Betelgeuse – the red giant, like the betel-stained mouths of older, rustic relatives – which marks the hunter’s shoulder; the blue supergiant Rigel marks his left foot.

Tracing constellations is less science than instinct – connect what dazzles, skip what dims. Like the puli kolam my mother coaxes from a lattice of dots (puli), tracing a constellation calls for selectivity – some stars you join, others you leave them be, and gradually, the desired pattern emerges. Far from city centres – in the absence of severe light pollution – there will be more dots to connect. Even in my little corner of the world, awash with halogen lights, a dozen stars blinked back – all is not lost yet.

It can be habit forming. As the autorickshaw puttered to a stop outside our gate, before heading into the building, I paused to gaze towards the grey-orange sky. Almost immediately, my eyes fell upon a blue-white star – scintillating, like the nursery rhyme “diamond in the sky”. The app said I was looking at Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. It was also the perfect foil for what I would see next – an unwinking brownish-red dot. Mars – elders in the family would’ve called it chevvai, literally “red-mouth” in Tamil. It is a malevolent one, local astrologers say.

In the next decade, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration plans to send astronauts to Mars on a three-year mission. They say the voyage to Mars will take astronauts six months, one way, but that evening Mars seemed to be parked right over our compound. I could not believe my luck. The oblivious teenagers lost in chatter walking down the street, the woman bent over the iron box in the blue cart across our building, the sleepy watchman sitting near the gate – I wanted to grab them all and show them the red planet, but a neo-convert’s zeal could be overwhelming, even off-putting.

After decades of ignoring the skies, my mind was aswirl with questions. Who is the equivalent of Orion in Indian sky lore? Where is Arundhati, the steadfast star, the priest asks the bride and groom about during the Tamil marriage ritual? Like the fiction it is adapted from, the Tamil film Ponniyin Selvan set in the 10th century opened with an ominous comet that foreshadowed succession trouble for the Chola Empire. Comets who have portended momentous events down the ages – don’t our troubled times demand the appearance of a comet?

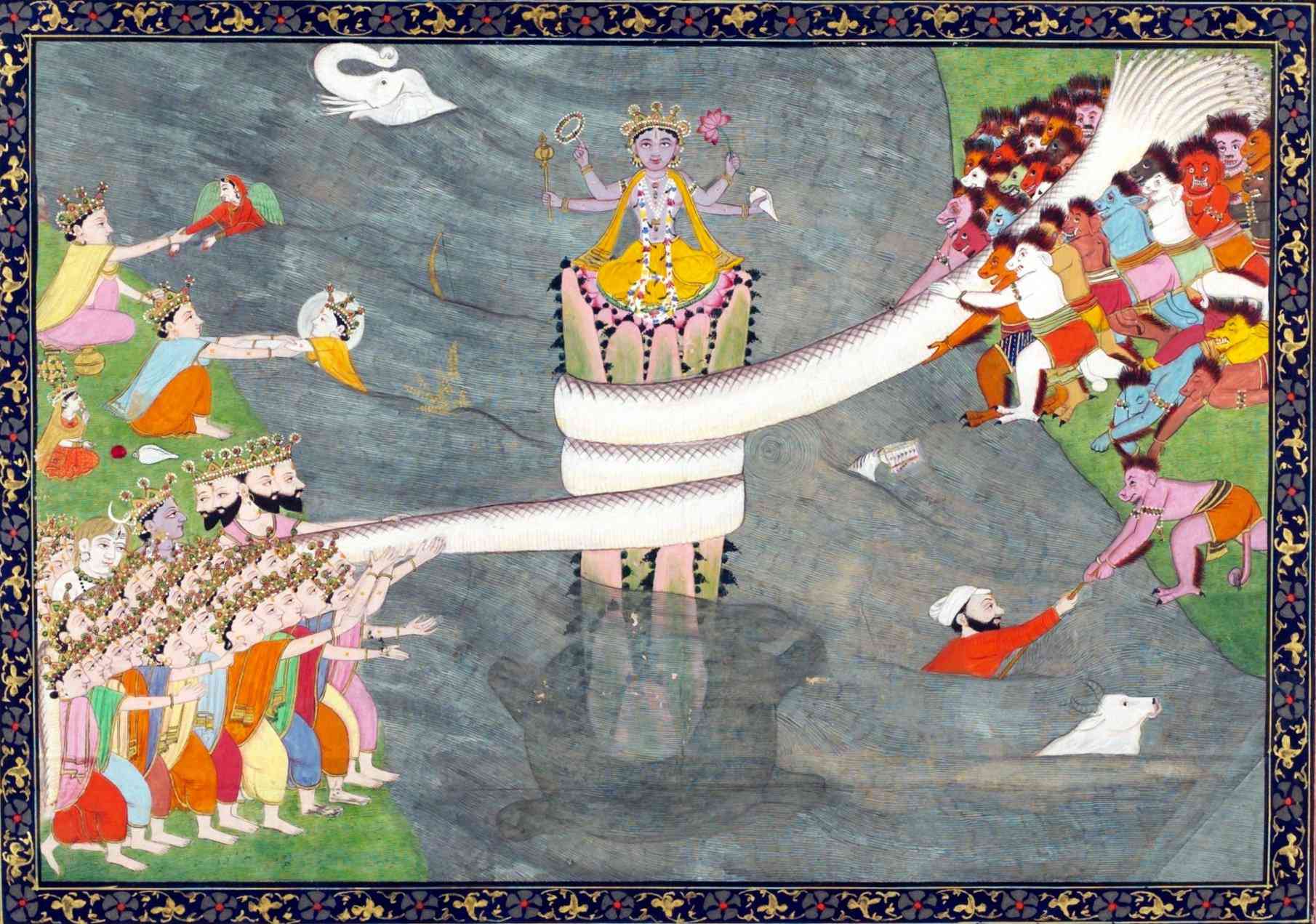

And the celestial commons humanity is losing sight of? The Milky Way has an Indian story. Rushdie writes: “When I first heard the tale in the great epic Mahabharata about how the great god Indra churned the Milky Way, using the fabled Mount Mandara as his churning stick, to force the giant ocean of milk in the sky to give up its nectar, ‘amrita’, the nectar of immortality, I began to see the stars in a new way.”

The Milky Way – lost, rumored, opalescent – awaits us beyond the spill of city lights. To glimpse the Milky Way, we will need to journey farther than our mottai-madis, past our compound walls, even beyond childhood memories – unlike Rushdie, most of us have never seen the fabled galaxy. But first, we must head to an accessible vantage point – with a smartphone app that will function as a guide to the stars – to sample wonder.

Vijaysree Venkatraman is a Boston-based science journalist. A version of this first article appeared in Madras Musings.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting