The world of popular Indian cinema, and its icons like Geeta Bali, had a powerful hold on the students. It was the only cinema they had watched back home, and in most instances, it was the reason they had made the journey to Poona.

The preceding years may have seen a profusion of mediocre (or worse) films in India, just as the Film Enquiry Committee had said, but even in their midst a few filmmakers like Raj Kapoor, Bimal Roy, Mehboob Khan and Guru Dutt, among others, had been making some outstanding movies. Their output was so remarkable that the decade was later dubbed the ‘Golden Fifties’.

A newly independent nation, with its innumerable hopes and just as many problems, seemed to have stirred these filmmakers into new directions. If there was romance and soft-focus beauty, there was also hard-hitting social commentary. Awara (1951), Do Bigha Zamin (1953), Pyaasa (1957), Mother India (1957), Kaagaz ke Phool (1959 – a feast for any film buff – marked that decade. Mughal-e-Azam (1960) was spectacular. Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962) hit the screens soon after the first students walked into the Institute.

It was an inspiring time to dream about becoming a filmmaker. The songs, and often the scenes, of these movies played unsummoned in their minds.

The fifties had also seen the birth of a new kind of cinema, spearheaded by Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (1955), a marked departure from the norms of the mainstream industry, realistic, shorn of glamour, largely shot on location, often with new faces, sometimes even with non-professional actors, and made on small budgets. Ray was prolific, sending out a knockout film every year, but there were others too, like Ritwik Ghatak with his quirky Ajantrik (1957) and Mrinal Sen with Neel Akasher Neechey (1958). The reach of these filmmakers was at first limited to Bengal – and even within Bengal a limited audience – and therefore unlikely to have been seen by students applying to the Institute.

Almost all these Indian landmark movies soon sat in the vaults of the Institute, either that belonging to the Institute’s own film library or in the Archive’s collection. The Indian films shared shelf space with till then unfamiliar titles – Battleship Potemkin (1925), Citizen Kane (1941), Bicycle Thieves (1948), Rashomon (1950), Wild Strawberries (1957), Breathless

(1960), La Dolce Vita (1960), etc., made by directors Sergei Eisenstein, Orson Welles, Vittorio De Sica, Akira Kurosawa, Ingmar Bergman, Jean Luc Godard, Federico Fellini, respectively. Films in Russian, Italian, Japanese, Swedish, French, and many other languages, told stories from other lands. Both the Indian and foreign films were critical parts of the history of cinema, and Jagat wanted to make sure his students would be exposed to them.

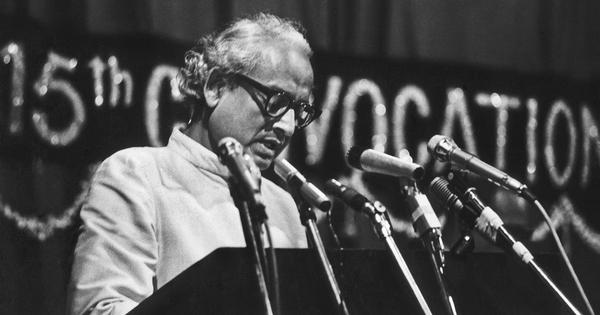

Jagat’s mission was to create filmmakers who would raise the standards of the Indian film industry, to make his brood of often glamourstruck students see beyond the formulaic genre films of the industry, to stop the blatant borrowings from Hollywood films. How do you foster originality? How do you broaden perspectives? How do you create social consciousness? How do you create a yearning for technical excellence? How do you expand the cinematic vocabulary of young filmmakers? How do you create a passion for cinema?

Jagat’s answer – the reason he had been so determined to build both the film library and the Archive – was simple. It harked back to his own experience as a student in America, and the eye-opening influence that international cinema had had on him. He believed that all of this cinematic heritage, both Indian and global, belonged to his young filmmakers.

So, instead of setting sail within only the Indian tributary, he went downstream where Indian cinema met the mother river of world cinema, the waters swirling with the output of multiple cinemas. The waters ran deeper there, the currents swifter, the ride adrenaline charged, jolting you to your very core.

At first, this ‘extensive exposure to the variety of cinema has an unsettling effect’ on students, Jagat noted. Which was what he wanted.

The contents of the Institute’s vaults would soon reconfigure the minds of the students. The seeds of the Indian New Wave were buried deep in those darkened underground spaces, sitting inside cans of celluloid stacked on shelf after shelf, ready to flower once exposed to the light in the eyes of the Institute’s students. Popular Indian cinema would have to share mind space with this newly discovered World Cinema. Geeta Bali suddenly had competition.

The impact would be transformational on many fronts. Like a potent drug, it was mind expanding. And every discipline would be affected. Acting students could now look to foreign films for inspiration. ‘Russian films, Italian films, German films, the Institute was a Khazana (treasure chest),’ recollected Rehana Sultan (Acting, 1965), the first Institute alumna to win the National Award for Acting. She described what she had found so revelatory:

‘We learned characterization . . . in real life, how will you react, how will you feel? How do you imagine? Sophia Loren ne kamaal ka kaam kiya (did amazing work). She portrayed a drunkard, a prostitute, but she was not, so how has she done it? Characterization and imagination. You see, you think, you do.’

In an interview in Hindustan Times, the celebrated actor Naseeruddin Shah (Acting, 1975) recalled seeing movies starring the likes of Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean-Louis Trintignant, who introduced him to new ways of thinking about acting.

The impact on other disciplines was similar. Students of cinematography had their eyes opened to the possibilities revealed by arthouse cinematographers like Subrata Mitra, who shot Satyajit Ray’s films; Raoul Coutard, who worked on a number of the French New Wave films; Gregg Toland, whose innovative deep focus techniques gave Citizen Kane its distinctive look.

Cinematographers R.M. Rao (1964) and Mahesh Aney (1979), a generation apart but fully in agreement about what they had learned at the Institute, said that its alumni were ‘way ahead when it came to experimentation’, for example, using bounce lighting to create the effect of natural daylight, long before it became a common practice in India. This was as much due to the training they received in their classes – Subrata Mitra, who pioneered bounce lighting, was a regular guest lecturer at the Institute – as their being ‘exposed to the best films of the world’.

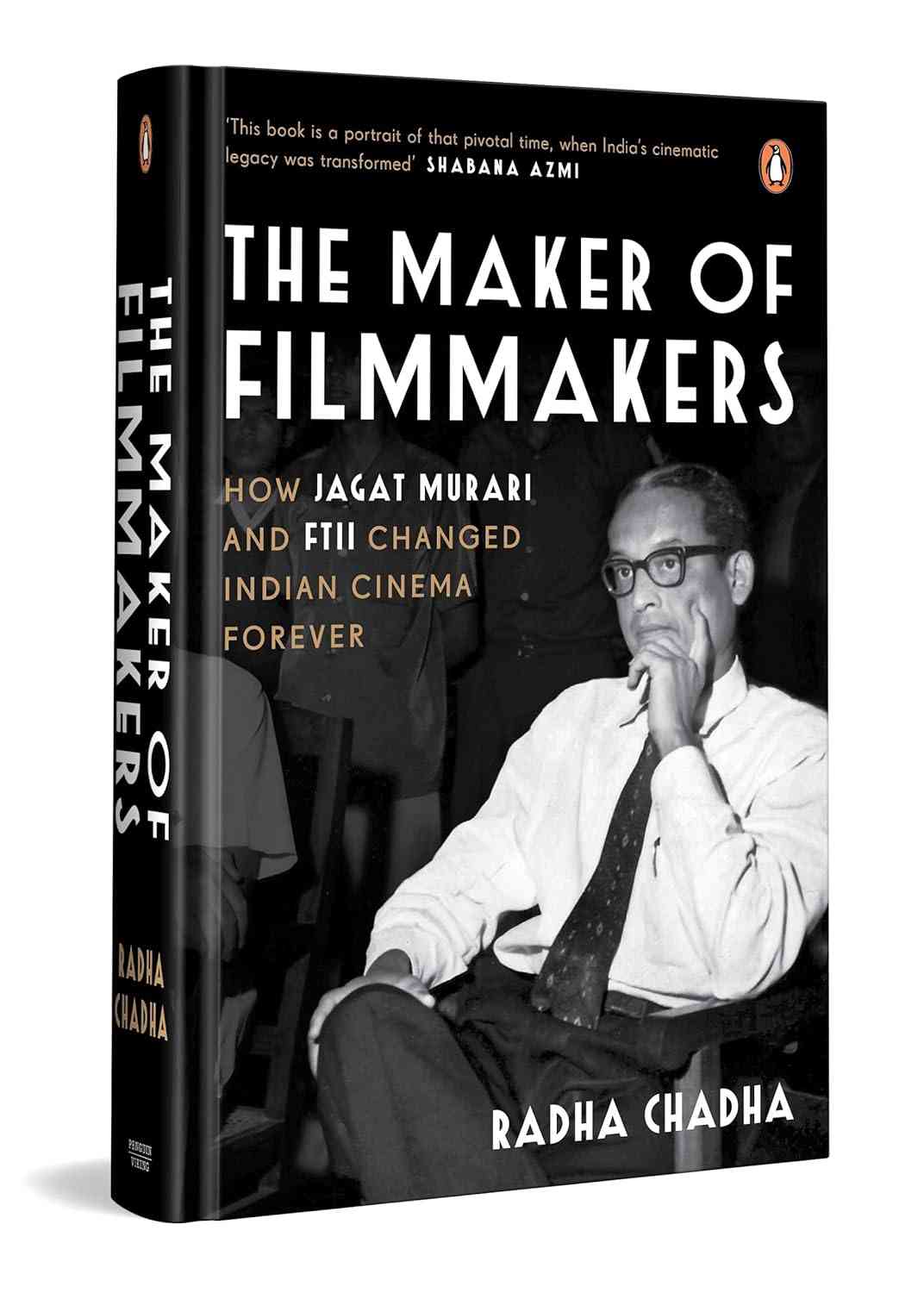

Excerpted with permission from The Maker of Filmmakers – How Jagat Murari and FTII Changed Indian Cinema Forever, Radha Chadha, Penguin Random House.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting