Some months ago, I met with two teenage girls at a shelter home in Karachi, who shared their stories of resilience and courage with me.

Hira and Sadia (names changed to protect their identities) were still minors when their lives took a devastating turn. They were abducted, forcibly married, and coerced into converting to Islam.

Their stories echo the silenced experiences of countless girls from Pakistan’s religious minority communities, where the intersection of faith, gender, and power often leaves young women with no agency over their own lives.

Pakistan’s population of over 240 million includes 3.8 million Hindus (1.6%) and 3.3 million Christian (1.37%), according to the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics 2023 census.

The country is home to over 19 million child brides – nearly one in six are married before the age of 18, and as many as 4.8m married before the age of 15.

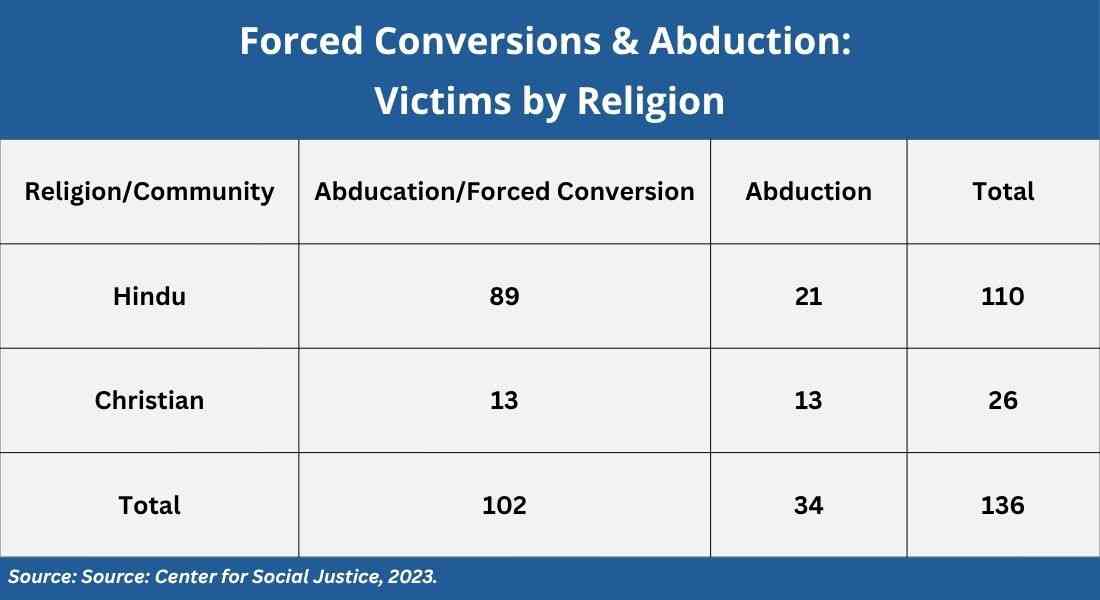

Between January and December 2023, there were 34 reported cases of abduction, and 102 allegedly forced conversions, according to a report titled Human Rights Observer 2024 – A fact sheet on key issues related to religious freedom and minorities’ rights in Pakistan, produced by the Centre for Social Justice, Lahore.

The highest number of cases were reported from Sindh province, home to most of Pakistan’s Hindu population. Punjab, where most of the country’s Christians live, accounted for 28 cases. There were 78 alleged victims between 14 and 18 years of age, nine over 18, and 25 under 14. The ages of 12 individuals were not available, while 12 were already married at the time of reporting.

Minority Rights March

Since 2023, activists in Pakistan have been organising an annual Minority Rights March, held to coincide with National Minorities Day, which is observed annually on August 11 since 2009.

It was on August 11, 1947, that the country’s founding father in his speech to the Constituent Assembly, days before Pakistan was “born” declared that religion has “nothing to do with matters of the state.” The white stripe in Pakistan’s flag symbolises the country’s religious minority communities.

Bhevish Kumar, a Hindu rights activist and key organiser of the March, described it as a grassroots movement aimed at addressing systematic discrimination and violence. He told Sapan News that various factors contribute to early marriages involving girls from minority communities, like the perception that converting someone to Islam brings “sawab” (religious rewards), besides aspects like poverty and lack of education.

Kumar questioned the legitimacy of the conversion process, which he said should take place in magistrate courts instead of mosques, where girls are often presented within hours of their alleged abduction, along with an age-certification document.

Pakistan is a signatory to international laws on child marriage, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the SAARC Convention on Trafficking in Women and Children for Prostitution.

The Child Marriage Restraint Act 1929, which sets the legal marriage age at 18 for males and 16 for females, applies across Pakistan. Sindh province and Islamabad Capital Territory each have a Child Marriage Restraint Act, passed in Sindh 2013 and Islamabad earlier this year, May 2025, upholding the legal age of marriage at 18 for both men and women.

According to a 2022 ruling by Justice Babar Sattar of the Islamabad High Court, any marriage contrary to the Child Marriage Restraint Act is void. However, laws are poorly enforced, mostly due to religious influence that frames conversion as a “sawab”.

To evade the Child Marriage Restraint Act in Sindh or Islamabad, the accused sometimes take victims to areas where the legal marriage age is lower.

The government is “unprepared and ambivalent” about forced conversions and early marriages in Punjab, Lala Robin, chairperson of the National Minorities Alliance of Pakistan, told Sapan News. He features in a documentary Hum Saya (Neighbour) that highlights the struggles of a Muslim man advocating for his Christian neighbour’s abducted daughter – a story of hope and courage.

When families file abduction cases and police recover girls, the courts often deny access to their parents, while allowing the alleged abductors to meet the girls, alleges Veengas, editor of The Rise News, Pakistan. So the girls continue to be manipulated.

Cases of a criminal nature should be treated as crimes, she told Sapan News, without attributing poverty, religion, or other factors.

Cases of “free will” or consensual inter-faith marriage do occur, but they are relatively few and often involve court marriages where the girls are not underage, says Veengas. She criticises the mainstream media for only focusing on cases that gain traction on social media.

Pakistan also lacks laws specifically addressing forced conversions, comments human rights activist Peter Jacob of the Center for Justice, Lahore.

Section 498-B of the Pakistan Penal Code prescribes a penalty of up to 10 years in prison for forced marriages, with a minimum of three years and a fine of 5 lakh rupees. However, this law is not applied to conversion cases, said Jacob, who is a recipient of the International Religious Freedom Award 2024 presented by the US State Department, and has authored several books on the lives and roles of Pakistani religious minorities.

One problem with the inapplicability of laws, he added, is that marriage certificates in conversion cases are promptly issued. Sometimes, courts ignore the official documents such as the parent’s marriage certificate or the National Database and Registration Authority documents that prove the girl is under 18, and instead accept the instant certificate, said Jacob.

Restrictions

There are legal and moral restrictions on conversions to Islam, asserts Mufti Saifullah Rabbani, a religious scholar at the seminary Jamia Binoria Aalamia in Karachi. For instance, those converting must be over 18 and understand fully what conversion entails, he told Sapan News. This requires proof of age and knowledge assessment.

He said his seminary does not conduct Nikah (marriage contract) ceremonies. Although state laws exist, religious laws such as Hudood Ordinances and Sharia laws are sometimes invoked, he noted. For example, predators present marriage certificates in court, and courts ignore the Islamic requirement of permission from the first wife of an already married man.

However, religious and political parties like the Council of Islamic Ideology, and the Ministry of Religious Affairs, have repeatedly prevented bills from being passed before Parliament that would outlaw marriage to minors, like the Religious Minorities Bill 2020, Prohibition of Forced Conversions Bill 2021, and the Bill Prohibiting Forced Conversion, 2016.

Opponents of such legislation contend that age cannot be used to limit or curtail faith conversions.

Some associates of shrines in Sindh, like Bharchundi Sharif and Lal Shahbaz Qalandar are widely perceived to convert minor girls and issue marriage certificates. Bharchundi’s Abdul Haq “Mian Mithu” denies this but protests from the Hindu community forced the political parties he has been associated with, Pakistan People’s Party and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, to drop him. In 2022, Britain listed him as a human rights violator in a Sanctions Report released by the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation HM Treasury.

Gaps in the justice system further facilitate the accused, says Peter Jacob. In two cases involving minor girls, the court accepted claims by the accused that the girls were over 18 years old. The judges, said Jacob, did not acknowledge other instances of forced religious conversion.

He added that it is crucial to call for an investigation into certificates issued at shrines and madrassas, which are not regulated by law. A collective inquiry could be of great help, necessitating the establishment of an inquiry commission, he said.

Jacob pleaded for civil society members and religious parties to initiate dialogue around these issues.

Advocate Luke Victor from Karachi who challenges forced conversion cases, refers to Sadia, who I had met. She was 13 in April 2019 when her khala, mother’s sister, took her to Imran, a married man more than twice her age who sexually abused her. He then took her to an undisclosed location and converted her to Islam, showing her as an adult in the nikah certificate. She escaped eventually, helped by Imran’s daughter.

The police refused to apply the Sindh Marriage Act, as requested by the state prosecutor. The court ruled that the nikah was valid rather than declaring the marriage null and void, said Victor. Thus, sexual interaction was justified; the five accused were acquitted. The case is now on appeal.

Shelter homes

When police recover girls whose families file abduction cases after their disappearance, the courts direct them to be placed in government-run shelters called Darul Aman, or in shelters run by nonprofit or legal aid organisations, sometimes in partnership with the government.

Impoverished areas in Sindh – Umerkot, Ghotki, Mirpur Khas, Sanghar, Tharparkar, Jacobabad – are hotbeds for such conversions, as highlighted by South Asia Partnership-Pakistan’s 2015 report, Forced Conversion by Religion. Families in these rural areas, including religious minorities, mostly work in labour-intensive jobs, and suffer from lack of political representation. Some 80% of Pakistan’s non-Muslims work in low-paid jobs, according to the report Religious Minorities in Pakistan, Human Rights Monitor, 2023.

However, journalist Veengas debunks the argument that girls convert and marry to escape poverty, pointing out that the men they marry are often not much better off – and besides, girls from affluent families also get converted. She also questions why these young girls, who may not fully grasp their own faith, are drawn to another religion.

Pakistan ranks sixth in the world for “child brides” – girls married before the age of 18, according to a UN Women report Costing Study on Child Marriage in Pakistan, 2020-2021.

The potential risks of early marriage include problems in childbirth, marital rape, exploitation, domestic violence, and mental trauma. Mahnaz Rahman, Resident Director of Aurat Foundation, emphasized that early marriages often lead to early pregnancies, as the girls’ bodies are not fully prepared.

Accused individuals often use puberty as a defence under Sharia law. However, the Federal Shariat Court ruled in 2012 (page 11) that puberty is not the sole factor determining marriage.

The rights advocate Luke Victor asserted that clerics often misinterpret this, focusing on the “puberty factor,” which creates confusion among judges.

Victor also referenced the case of a Sikh girl Simran*, who was 15 when she was allegedly abducted in January 2024. A police case was registered at the Frere Police Station, Karachi, the 24-year-old accused then reportedly took the girl to Rajanpur, Punjab, to evade the Sindh Marriage Act.

The magistrate court was “very lethargic,” complained Victor. “Magistrates are very reluctant to pass orders, resulting in several months’ delay”.

The Zainab Alert Bill 2019, initiated after the abduction and murder of a six-year-old girl, mandates police to take action to recover kidnapped minors by filing a First Information Report or FIRs within two hours after a child is reported missing. However, they are often involved in “mukmuka” (compromises), alleges Victor.

Police reforms

The police often initially refuse to register FIRs, and even when they do, girls are not consistently returned to their families, Veengas told Sapan News.

In Hira’s case, a religious cleric was arrested on charges of harbouring both the victim and the alleged abductor. While the alleged abductor was denied bail, the cleric was granted bail on his third attempt.

Ghazala Shafique, a Karachi activist, told Sapan News that she has rescued 11 minor Christian girls. Six of the cases are pending in court. Issues include concerns about the legal complexities if a girl becomes pregnant, as Christian marriage law nullifies such marriages despite faith conversion certificates.

Families face immense pressure in such cases including from the accused who may reside in the same neighbourhood as the victim, Shafique said. Sometimes families withdraw the case due to threats.

Shafique believes there is a need for separate shelter homes for minor girls where they can be supported emotionally and physically, as sometimes older females in the existing homes manipulate them after involuntary conversions.

When I had met Sadia at the shelter home along with Hira, she shared her mental agony and questioned society’s troubling acceptance of a 13-year-old girl marrying a 35-year-old man. Her trauma was exacerbated by the threats and blackmail that her younger brother would be killed, which kept her with her abuser until she found the courage to break free.

The state should recover abducted girls and parents should accept and support their daughters, she said. Social stigma around sexual exploitation discourages girls who have been abducted from confiding in their parents.

Sadia now studies in the ninth standard in Karachi and continues to attend court hearings about her case.

Shaeran Rufus is an independent journalist from Karachi. She has a degree in media studies from Bahria University, has worked at Capital TV and Express Tribune, and is a Fellow of the Pakistan Press Foundation. She is currently studying at Chongshin University Graduate School of Theology (MDiv), South Korea. Her X handle is @ShaeranRufus.

This article was first published on Sapan News.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting