“For Good Services Rendered”. The commendation emblazoned across the gold medal is remarkably understated. For, when the Gramophone Company of India handed it to vocalist Narayanrao Vyas in 1935, he was more than just “good” – he was a prodigious recording superstar. He had broken every sales record for 78 RPM discs for Hindustani music. And in the decades that followed, he would go on to cut an impressive total of nearly 150 shellacs.

The medal, now dulled with age but a prized heirloom, sits in the Mumbai home of his son, vocalist Vidyadhar Vyas – a testament to the life and legacy of a rare classical vocalist with an easy and smart grasp of emerging audio technologies. Not only did Vyas take to the phonograph with ease, but he, along with Balgandharva and Sundara Bai, also played a pioneering role in the inauguration of Bombay Radio in 1927.

“At a time when many classical musicians were still wary of recording devices, he had made studied use of technology to increase his listener base,” said Vidyadhar, who just released Gayanacharya Pandit Narayanrao Vyas Smriti Granth, a collection of essays and interviews by musicians, critics, associates and family on his father’s life and art, compiled and edited by music scholar Suneera Kasliwal Vyas.

The relationship was mutually beneficial: while Vyas embraced recording technology, his music also proved highly lucrative for commercial record companies. “He was a musician who married technique and technology in a way that was far ahead of his time,” Vidyadhar said.

Star power

Vyas’s first album, released in 1929, had been a runaway hit. It featured a bandish in raga Adana, Eri mohe jaane de, on one side and an enduring bhajan, Shyam Sunder Madan Mohan, on the other. Several of his subsequent albums also enjoyed considerable success, further cementing his popularity with audiences.

Over the years, his dulcet voice, brisk style, the rigour of the Gwalior gharana and vast repertoire – khayal, tarana, thumri and bhajan – reached thousands of homes on multiple devices.

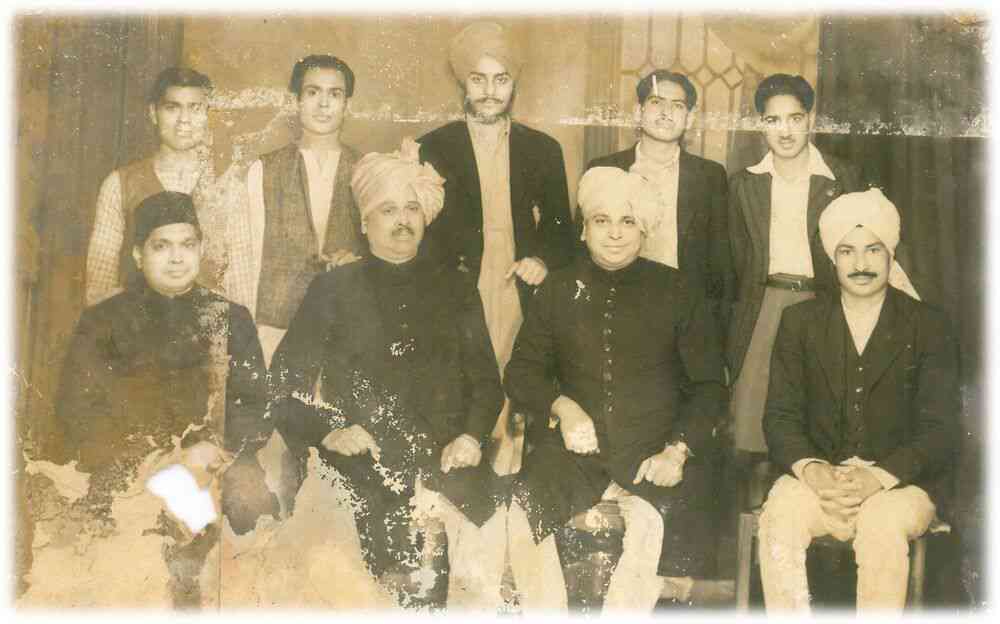

He drew fully on his star power, singing to packed houses, living in style and dressing, by many accounts, “tip top” in jackets and turbans. He even had the chutzpah to organise his own concert in Pune’s Kirloskar Theatre in 1930, a poster of which shows top tickets selling at a hefty Rs 10 and the cheapest at nine annas.

By compressing a music that is known for its expanse and disdain for time into three-and-a-half-minute tracks, he had made ragdari music easy listening.

To be sure, he was not the first classical artist to be recorded – phonographs had already been around for nearly three decades. The indomitable Gauhar Jaan had led the disc revolution and had been followed by a galaxy of classical stars, including Jankibai, Malka Jan, Peara Saheb, Rahimat Khan and others. Vyas’s contemporaries such as Faiyyaz Khan and Hirabai Barodekar had recorded music too. But several had held out, baulking at the idea of making high art accessible to the masses for repeat hearing or outright fearful of a strange new medium.

Where Vyas scored over others was in the precision with which he crisply abridged for shellac the entire khayal universe, especially of the Gwalior gharana.

“To present most aspects of a raga’s full persona – the sthayi (refrain) and antara (stanza), alaap, layakari (rhythm play) and taan – in such a short time and impress listeners is a really tough challenge. It is hard to even imagine how he did this,” writes Jaipur gharana vocalist Arun Dravid in his tribute for the collection. “Technicians would tell musicians that they could rehearse as much as they wanted but once the recording began it had to stop at three and a half minutes. Make a mistake and it would go public. Artistes must have performed like they had a sword hanging over their heads.”

Vocalist Madhup Mudgal says that his guru, Kumar Gandharva, believed Vyas’s recording of Gaud Malhar in 78 RPM was the most perfect representation of the raga, a near impossible feat.

Still, to reduce Narayanrao Vyas to a “recording phenomenon” would be unfair. As one of the primary disciples of the legendary reformist Vishnu Digambar Paluskar, he lived through a period of intense transformation in every field of Indian classical music – from its form and exponents to its platforms and audiences. But no matter the shifts, Vyas adapted effortlessly, smartly packaging his art to suit the time and context.

Promising future

Narayanrao Vyas was born in 1902 in Kolhapur, a city that had a strong classical tradition, thanks to the large number of great musicians invited to perform at the royal court – Alladiya Khan was appointed there as chief musician – and at the Mahalaxmi temple. Growing up exposed to this rich cultural environment, the Vyas siblings, Narayanrao and Shankarrao, developed impressive singing skills.

In the early 20th century, Paluskar was on an evangelical mission across Maharashtra to find fresh talent to mentor in a field dominated by traditional practitioners. He had just set up the Bombay branch of the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya he had inaugurated seven years ago in Lahore and he was in search of promising students. During this hunt, he discovered the Vyas brothers.

For the Vyas family, struggling to make ends meet, Paluskar’s gurukul offered a promising future. Life at the Bombay school was strictly regimented and, by all accounts, the guru was a disciplinarian but generous and affectionate. Among their classmates, the Vyas brothers had many future Hindustani greats, including BR Deodhar, Omkarnath Thakur, Laxmanrao and Shankarrao Bodas, Vinayakrao Patwardhan. All of them learned under the newly-minted Paluskar system that departed from tradition by including a prescriptive syllabus, notated music, a fee structure, graded classes, examinations, certification and so forth.

A decade later, when the Vyas brothers graduated, they were instructed to go and teach music in Ahmedabad. And while there were occasional concerts at weddings of seth families, Vyas was not entirely happy. “My father was at heart a performing artist and he would tell me that even when he was teaching, he was daydreaming of singing on stage,” Vidyadhar said. Eventually, Vyas moved back to Bombay, although his alma mater had shut and all that the city had were his musician classmates from school.

As fate would have it, the city gave him the debut he sought. Vinayakrao Patwardhan, who was scheduled to perform at a prestigious Ganesh Utsav concert, had fallen sick and recommended his guru bandhu, swearing to return the fee if the youngster failed. Vyas didn’t – he impressed the audience and bagged many more concert bookings.

His son credits Vyas’s success in part to his embrace of the brisk stage craft of Marathi natya sangeet, especially Balgandharva – he kept his music lean.

His classmate Shankarrao Bodas summed up his appeal in a tribute on his 75th birthday: “He figured out his audiences quickly. In this regard, Narayanrao was a successful performing artiste. When he was in the midst of the erudite, he could present khayal, tappa or thumri in all their intoxicating glory.” One time, at a concert for the merchant’s chamber in Kanpur, he took a quick look at the gathering and settled on his popular repertoire of bhajans and short compositions.

Balancing act

The buzz around the young singer grew over the next two years, attracting the attention of recording companies on the lookout for artistes with box office appeal. In 1929, HMV approached him. It was a striking opportunity, but according to accounts, Vyas took six months to think through what music to present – and how. It is said he listened to a lot of Zohrabai Ambalewali, Bal Gandharva and Rahimat Khan to get a sense of the tayyari needed because there was no margin for rerecording or editing.

An astute performer, he later told his friend, writer Ramakrishna Bakre, that in his curation for HMV, he was keen to balance his artistry with the needs of listeners and recording companies. Bakre wrote, “He told me: ‘Gramophones will take my music to every home. To ensure that this music becomes popular and also sells well I suggested that we record on one side a popular bhajan and a chhota khayal on the other.’”

Vidyadhar recalls his father’s strategy to ensure precise time management: establish the bandish to frame the raga, then unfold aspects like alap, bol alap, tan and so forth swiftly without any repetition. He even posted two disciples on tanpuras to stand in front and behind during the recording, and their task was to mark the passage of every minute with a gesture. If the one at the front failed to draw his attention, the one at the back was to prod him gently.

The planning served him well and continued to serve him for several recordings, among the biggest sellers of his time. His hits included the delectable Sakhi Mori Rum Jhum in raga Durga, Neer Bharan Kainse Jaun in raga Tilak Kamod, Tuma Jago Mohan Pyare in raga Bhairav, Neer Bharan Main Chali Jaat Hun in raga Malkauns. Concertgoers rarely let him leave the stage without singing the bhajan Radhe Krishna Bol Mukh Se.

Another blockbuster was his Malgunji jugalbandi with Vinayakrao Patwardhan, Ban Mein Charavat Gaiya. Though khayal is traditionally a solo form, their vocal duets were hugely popular. As Delhi gharana veteran Krishna Bisht notes in an interview for Smriti Granth, Hirabai Barodekar and Saraswati Mane had sung jugalbandis in the past, but those singers were considered an “uneven” match.

Vyas remained an active musician until the end of life. A fortnight before he died in 1984, he sang on radio, recording three ragas for broadcasting at different times of the day – Asavari for morning, Gaud Sarang for afternoon and Malgunji for night. “His voice was as sweet and as firm as ever,” recalled his son.

All images courtesy Vidyadhar Vyas.

Malini Nair is a culture writer and senior editor based in New Delhi. She can be reached at writermalini@gmail.com.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting