In a government hospital ward in Bengaluru, as the terrible tragedies of the Covid pandemic played out around her, Sumana Chandrashekar was battling for her life. Yet, even in those lonely hours between waking and delirium, swathed and restrained, there was only one thing the ghatam player wanted to save even more than her breath – her left wrist that hits the resonant thom.

As the doctors plunged an IV needle into her left wrist, she pleaded into her mask, muffled and unheard: “Carefully please. Don’t kill my thom.” But kill her thom the needle did, and in psychogenic solidarity, the ki and ta collapsed too. For nearly a year, they stayed dead. , until she returned to the stage and played her beloved pot once again.

Unless you are made of stone, Chandrashekar’s intensely humane memoir, My Journey With Ghatam, will leave you in tears. The body, with all its vulnerability and strength, dominates the book – the recalcitrance and magic of the fingers, the inflamed wrist, the softness of the belly where the ghatam rests, her shorn head, the thighs where the potter paddles the pot to a perfect pitch, and above all, the strength of the female form.

“The body fascinates me,” said Chandrashekar. “Even when I was learning from my guru, I was driven by the question: how is my body learning? The compositions and techniques were important. But how were my fingers responding? What was happening to my shoulders? Where is a particular sound located in my body? The muscle memory kicks in first, long before you start going deeper into music.”

You don’t need to be a fan, connoisseur or even a music lover to enjoy My Journey With Ghatam. It is a rumination on life, labour and art, but it is also a down-to-earth investigation into the practices and hierarchies in Indian music systems. Along the way, Chandrashekar speaks of the fond curiosity her ghatam draws from common people, not the distant reverence reserved for classical instruments.

“People want to touch it, feel it, hear it,” she said. “When children ask to beat on it or whisper into it, I am thrilled. This, after all, is also the ghada and the matka of every home, an everyday object.”

But for all its apparent simplicity, the ghatam has a complex place in Carnatic music. It made its appearance on classical music only in the late 19th century and became more visible in the early decades of the 20th century. But it was largely dismissed as a non-serious instrument by classicists because of its everyday origins, its folk roots and the fact that it was often used for comic effect in street and theatrical performances.

Even today, it usually sits on the periphery of a concert ensemble – while the mridangam presides – and is tellingly classified as an upa pakka vadya (secondary percussion) along with the kanjira and morsing. To add to the precarity, lead musicians can leave it out altogether.

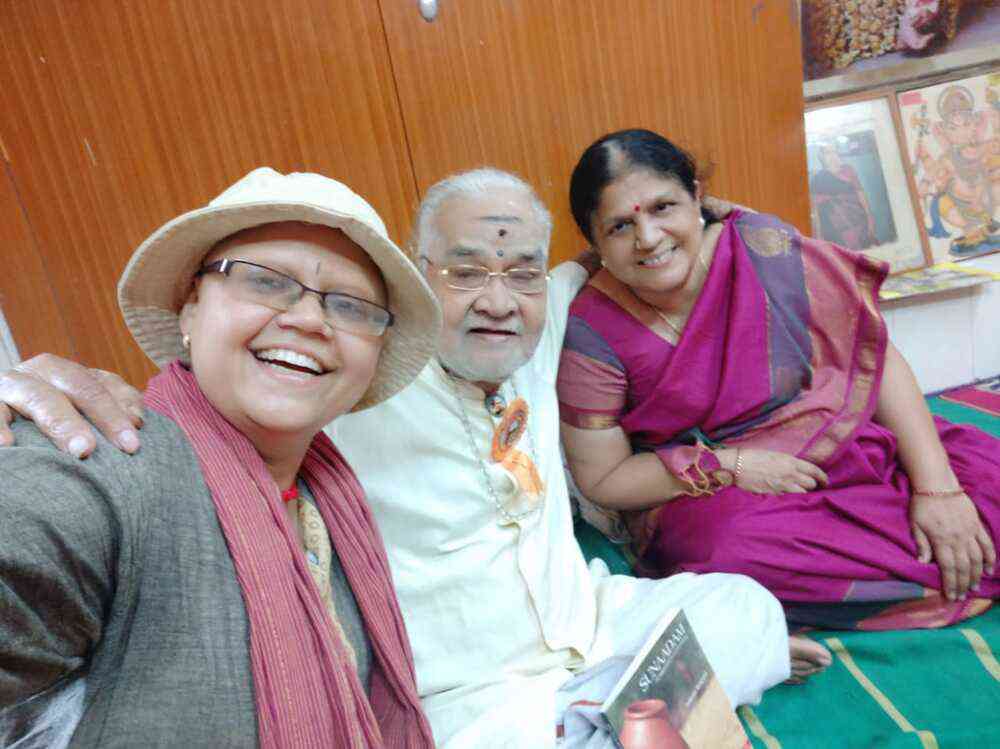

Chandrashekar trained under the formidable pioneer Sukanya Ramgopal, one of the first women to break into the male-dominated world of percussion. Her story as a percussionist is riveting on so many counts that it is hard to single out just one. But if you had to, it would be this: in a field ruled by men, and on an instrument as rare as the ghatam, she stands apart as a woman who refuses to conform – on stage or off. From her kurta-pajama and turban (or hat) attire to her low tolerance for the entrenched misogyny of music establishments, she defies the image of the bejewelled, deferential femininity of the Carnatic cliché.

Gendered space

Ghumki is an onomatopoeic word – the gloriously deep sound the ghatam makes when the palm strikes the mouth of the pot. But that sound lands better if the ghatam is pressed against the stomach for greater control and resonance. Conventional wisdom holds that the potbelly must be bare for maximum impact – what Chandrashekar’s book jokingly calls the rendu ghatam (double pot) advantage. This was just one more reason why the ghatam remained off-limits to women for decades.

Which is why, when Sukanya Ramgopal, a determined young learner, sought to study under the ghatam maestro Vikku Vinayakram in the mid-1970s, the answer was a firm no, even though Ramgopal was no neophyte. By this time, she had already matured as a mridangam player under the guidance of Vinayakram’s father, the legendary percussionist TR Hari Hara Sharma.

Chandrashekar’s book traces the roots of Vinayakram’s resistance. In 1979, the “open shirt” belly factor was being discussed in Carnatic circles, with the Tamil magazine Kalkand raising the question: “Pengal ghatam vasikkalama (can women play the ghatam)?” To this, Vinayakram replied, “Not in our culture.” Reared in a more conservative era, the ghatam legend held on to this view until he encountered the world beyond: in time, he taught not only Ramgopal but also Chandrashekar, with warmth and generosity.

But once she left her gurukul, Ramgopal ran into the cruelty of conservatism and patriarchy. She has often spoken of mridangam stalwarts who refused to play with a woman ghatam musician, of being turned away at concert venue gates and of breaking down in humiliation. Yet, despite these challenges, she kept moving forward, striking out on her own and setting up a ghatam ensemble three decades ago.

That did not make things for her young protegee in the new millennium, though. Thirteen years ago, when Chandrashekar joined the line of aspiring performers, she ran into the same walls all over again. And in her case, there was an even bigger irritant for the men who run music establishments. She looked and dressed “different”.

As a child of just six, as she puts it, “the hair on my head decided to leave”. One might expect this to have been a traumatic event, but she writes about it with characteristic humour and acceptance: “When all my friends had to spend at least fifteen minutes combing and plaiting their hair before catching the early morning school bus, I felt lucky I was able to sleep those extra fifteen minutes, then just flip my cap on and leave. In a car or on a bike, I could allow the breeze to wash over my head while others struggled to keep hair from failing on their eye or getting dishevelled.” Naturally, San-Te, the protagonist of the film The 36th Chamber of Shaolin, became her hero.

When the time came, Chandrashekar chose to take the stage wearing a nattily-tied turban or hat. As for the sari, it just wasn’t her skin, she says. She would arrive at venues in a kurta-pajama and turban, only to be met with astonished outrage from organisers who felt she was disrespecting tradition by not adhering to the Carnatic “uniform” for women. The kurta-pajama, she was told, was “un-Carnatic”, “odd” or “Islamic”, and the hat, “Western”. Among the many rebuffs she endured, “Get out” was perhaps one of the least offensive.

Part of the reason why she says she felt ill-equipped to deal with the hostility she faced later as a performer was because her family and guru were both remarkably progressive. “I get to choose how I appear, how I define my space,” she said. “In my wildest imagination, I don’t see myself conforming to the norm of how I should look. I find it hard to grapple with how normalised patriarchy is in this field.”

Even after she gained recognition, Chandrashekar continued to suffer small cruelties on stage: frequent signals to stop from other musicians, subtle forms of sabotage, and demands for “restraint”. As she points out, restraint is a gendered virtue – only men get to expect it of women.

Creative possibilities

But none of that sniping and hostility left Chandrashekar bitter. She is far too busy enjoying the creative possibilities her ghatam opens up: the joys of discovering the handpan and the many lives connected to her instrument. “Accompaniment is one space, but I am not tied to it,” she said. “The ghatam is so amenable to all kinds of experiments – fusion, dance, storytelling, solo interactive sessions, theatre.”

Chandrashekar has a close and abiding connection with the potters of Manamdurai in southern Tamil Nadu who craft the robust ghatam played by the musical lineage she belongs to. Here, the clan of the great ghatam maker Ulaga Vellar and his son Vellachami have pioneered the art of making pitch-perfect ghatams since the 1940s, a skill that needs both deft hands and sharply-tuned ears.

With his passing and that of his equally gifted son Kesavan, this legacy now sits with UVK Ramesh. In Manamadurai, while the men season the clay and work at the wheel, it is the women who take on some of the most critical tasks, from sifting and smoothing the clay to paddling it to a particular pitch. It is this latter fascinating task that makes an ordinary pot different from a ghatam.

Today, it is the clan matriarch K Meenakshi, fondly called paatti, who presides over the paddling. “The pot sat on her thighs, tender like a newborn,” Chandrashekar writes. “With a piece of round granite stone in her left hand and a flat wooden ladle on her right, she began to paddle the raw pot. The right hand on the outside moved in tandem with the left hand that worked on the inside.”

This is a painstaking and painful task: every single pot is paddled between 2,000-3,000 times to strengthen it. Much of this labour is rarely acknowledged or documented. Crafting the pot with a specific pitch is incredibly hard work and it needs an understanding of the nature of the clay, baking temperatures and several small factors that only experience can bring.

“I have deep reverence for the craft and its makers,” the musician said. “What goes into this instrument that sits on my lap as I do riyaz or sit on the stage, the labour, the material that gives me the strength to play? If it had not been for that experience, I would not have been the artiste I am today.”

All images courtesy Sumana Chandrashekar.

Malini Nair is a culture writer and senior editor based in New Delhi. She can be reached at writermalini@gmail.com.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting