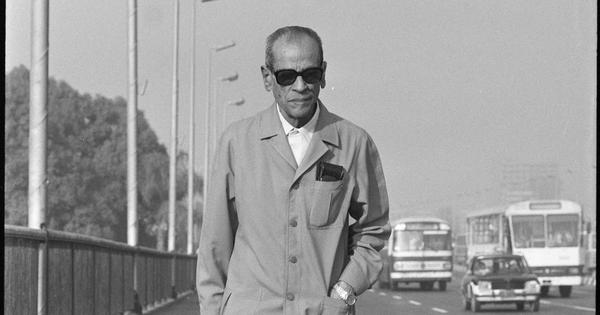

Naguib Mahfouz (1911–2006) was an Egyptian novelist, short-story writer and screenwriter. He spent his entire life in Cairo, the setting for almost all his fiction. He is best known for The Cairo Trilogy – Palace Walk (1956), Palace of Desire (1957) and Sugar Street (1957) – which follows succeeding generations of a Cairene family, the Abd al-Jawads, from the First World War until the Egyptian revolution of 1952. In 1988, Mahfouz became the first, and so far, the only Arab writer to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In 1994, when he was 82, Mahfouz was attacked in Cairo: an Islamic extremist, apparently acting on a religious edict related to Mahfouz’s controversial 1959 novel Children of Gebelawi, stabbed him in the neck. After this assassination attempt, which left him with permanent nerve damage, Mahfouz was unable to write for extended periods, and his freedom to roam Cairo was much restricted by concerns for his safety. But he could still wander the city in his dreams, and he could still write down those dreams, capturing them in a few swift strokes: he published them in a series of vignettes in the Egyptian magazine, Nisf al-Dunya, and in two books, the second published posthumously.

Now, at last, this second volume has been published in English, as I Found Myself: The Last Dreams. The vignettes are translated and introduced by the acclaimed Libyan-born British-American novelist, essayist and memoirist Hisham Matar, whose wife, the equally acclaimed American photographer Diana Matar, has provided accompanying photographs.

Dreams and imagination

Most of Mahfouz’s vignettes begin, in translation, with the phrase I found myself – or sometimes, I saw myself – thus alerting the reader that Mahfouz is about to share glimpses he has lately received into his own inner world of imagination, memory and political commitment, and as well into his subconscious. Like any dreams, these glimpses were initially unmediated by Mahfouz’s conscious will, but as Hitam Matar points out in his introduction, in our recounting of dreams, we act as editors, choosing what to leave out, what to emphasise, and sometimes adding new bits.

Matar also points out that Mahfouz’s dreams are those of an old man; they can be regretful about missed opportunities, and melancholy about the dead, who are often encountered as living presences. Very many of the dreams are concerned with loss of one type or another – unsurprising, given not only Mahfouz’s age, but also all that the attack of 1994 had caused him to lose.

One lost love, B, appears in several dreams. As befits dreams, her appearances do not follow the rules of chronology: we meet her in dream 203, when she’s already burdened by old age, but in dream 206, she’s young again, and in dream 207, where she’s unnamed, she’s dead, though she reappears in subsequent vignettes.

Dream 206: I found myself in a spacious and elegant hall. Gathered to one side were my family and friends and, at the opposite end, a door opened and through it my sweetheart B. entered laughing, followed by her father. I lost all self-restraint and held my arms open wide. The Imam began writing in the marriage book. Joy overtook everyone. My mother congratulated the bride and burned incense.

Dream 207: I found myself walking down a long road. A window of one of the houses to my left opened and through it appeared a woman’s face. Although her beauty had disappeared behind a thick veil of ill health, and it had been fifty years since I had last seen her, I immediately recognised her. In the morning, I was deeply unsettled when, reading the newspaper, I came upon her obituary. I was profoundly saddened and wondered which of us had visited the other at that hour of death?

The vignettes concerning Mahfouz and B hint at a narrative, a story, which the reader may choose to elaborate – as in the assumption that the beloved in the succeeding dreams 206 and 207 are indeed the same woman, B. But most of the vignettes resist interpretation; they are fragments untethered from plot, and hence from resolution.

Though many of the vignettes are intimate and personal, just as many reflect Mahfouz’s love of freedom, particularly of political freedom, or else his political anxieties, or else they offer social commentary. A handful are funny: three seem to reflect Mahfouz’s perhaps hidden desire that he’d been a famous footballer.

Matar says the swiftness and brevity of Mahfouz’s vignettes suggest their author was trying to catch at clouds, or to rescue fading images from oblivion; the same thing could be said of his wife’s photographs.

Complementing with photographs

Diana Matar began photographing Cairo just as Mahfouz began writing down his dreams; she then kept her photographs in a drawer for years. Her husband says: “Very much like an unforgettable dream, the images she captured are vivid, haunting, oddly mobile, uncertain.” The reader, or viewer, will surely agree, and though her striking images do not offer direct commentary on Mahfouz’s vignettes, they complement them wonderfully, and will help readers unfamiliar with Cairo both to visualise this, the setting for Mahfouz’s dreams, and, as well, to conjure its atmosphere.

How did this translation come about? Hitam Matar explains: “One Sunday morning as I drank my coffee at the kitchen table, I thought of translating a couple (of vignettes) for Diana, and found by the time she was up I had done a dozen.” He mentions that he found the work easy; that sense of ease is reflected in his translation which never feels laboured. Sometimes it captures a sense of poetry – words “swam across early moist air” – and it captures mood vividly. Here, melancholy.

Dream 243: I found myself searching for evidence that my love was not an illusion but real. My lover had departed in the glory of her youth, and by now the witnesses too were gone. The features of our street had changed, and in the place of her house with its flower garden a high-rise block stood, densely populated. Nothing remained of the past except memories without proof.

Between Mahfouz’s exploration, in old age, of his own self after trauma, Diana Matar’s shadow-drenched images of fleeting moments in Cairo, and Hitam Matar’s fluent translation from Arabic to English, this is a thrilling book. Hitam Matar professes pleasure in imagining Mahfouz himself leafing through it, “discovering his own invisible lines between dream and image”, and saying to himself “of course”. The reader is likely to share his pleasure in imagining the same.

Rosie Milne is the author of the novels How to Change Your Life, Holding the Baby, Olivia & Sophia and Circumstance.

This review was first published on Asian Review of Books.

I Found Myself: The Last Dreams, Naguib Mahfouz, translated from the Arabic by Hisham Matar, Viking.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting