The island of Great Nicobar has numerous gentle bays that open into the Andaman Sea. One of them is the Galathea Bay – its sandy shores are widely known as the nesting site of giant leatherback turtles, the largest turtle species in the world.

A lesser known fact about the bay is that until 2020, maps prepared by a government research institute showed that it harboured coral reefs.

Corals are a Schedule I species under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. This is the same status granted to tigers, Gangetic dolphins and elephants – all these species enjoy the highest level of protection from hunting, poaching and trade.

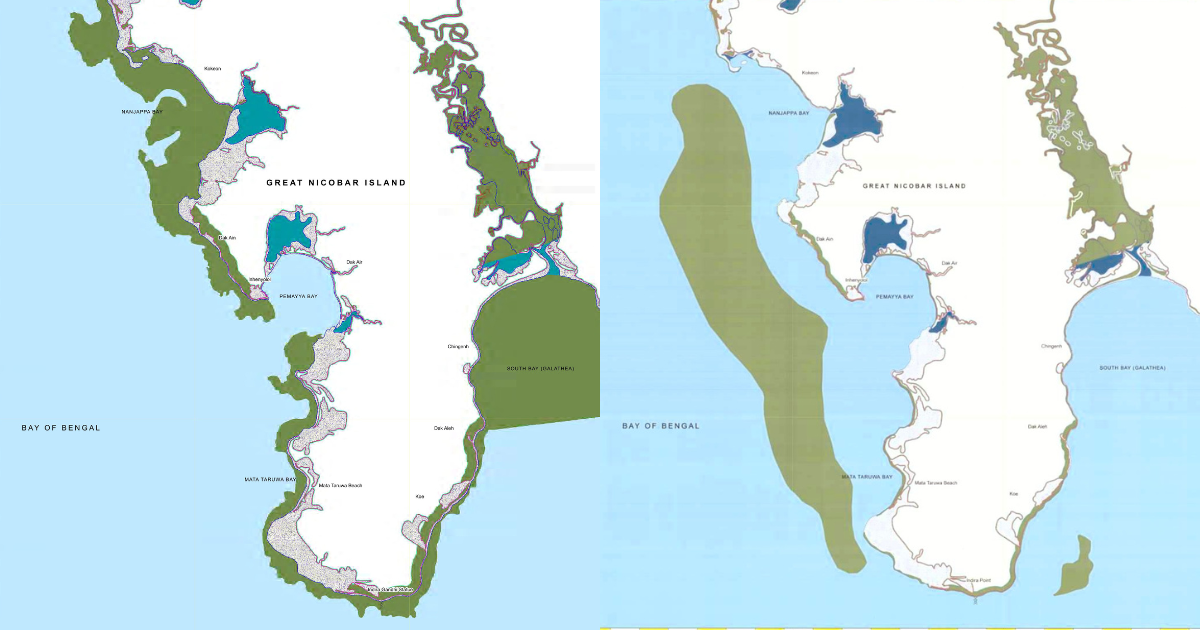

Apart from Galathea Bay, the 2020 map prepared by the National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management in Chennai, which functions under the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, also showed coral reefs hugging several other shores of the Great Nicobar, particularly in the south and the west.

But an updated map prepared by the same institute in 2021 contains a dramatic change. In this map, corals are completely missing along the coast of the Great Nicobar, including in Galathea Bay. Instead, they are marked in the middle of the sea, away from the shores.

This can be seen in the maps below – the coral reefs are marked in light blue.

The Great Nicobar is India’s southernmost island. In 2021, the government laid the ground for a mega infrastructural project on the island, the centrepiece of which is an international container transshipment terminal to be built along the Galathea Bay. The terminal is one of the four components of the Rs 81,000-crore Great Nicobar project – the other three are a power plant, a greenfield international airport and a new township.

In the run-up, between 2020 and 2021, it was not just coral reefs that moved on the maps of Great Nicobar.

In the 2020 map prepared by NCSCM, a green band lines almost the entire coast of the island. It depicts the area of the island categorised as IA. This category of land enjoys the most protected status among coastal lands under the Integrated Coastal Regulation Zone Notification, 2019, which governs the conservation and development of India’s coasts.

It includes coral reefs, mangroves, turtle nesting grounds and other areas that are environmentally “most critical”, are “ecologically sensitive” and “play a role in maintaining the integrity of the coast”.

To protect these lands, the notification prohibits a range of activity on them, including the destruction of corals, setting up of new industries, and building of major harbours and ports.

The entire Galathea Bay fell in this category in the 2020 map. But the 2021 map, which is featured in a document uploaded onto the Andaman and Nicobar forest department website in 2023, contains a vast change – the green band along Galathea Bay is missing, indicating that this area does not fall under the IA category anymore. Further, the rest of the coast is depicted with a much thinner green line than on the 2020 map.

Experts fear that these changes on the map may be linked to the government’s new plans for land use on the island.

“Coral reefs, turtle nesting sites, megapode nesting grounds, mangroves etc do not and cannot magically disappear to suit the convenience of the project proponent,” Ashish Kothari, an environmental researcher stated in a submission to the National Green Tribunal in July this year. Kothari is a petitioner challenging the Great Nicobar project, arguing that it would do irreparable damage to the island’s ecology.

Experts familiar with the region also doubt that the updated map is credible.

“I would really question this map. This is not accurate for sure,” said Vardhan Patankar, a conservation impact director with the United Kingdom-based social impact and sustainability organisation GVI. Patankar is a coral reef ecologist and has dived several times in Great Nicobar as part of his research.

He noted that corals “grow well” on seabeds at depths of “between 5 to 25 metres”. He added, “Sometimes we also find them up to 60 metres, depending on visibility, but those are patchy corals, and not a reef.”

He explained that corals would “not grow beyond a certain depth in the ocean” because they need sunlight to reach them for photosynthesis.

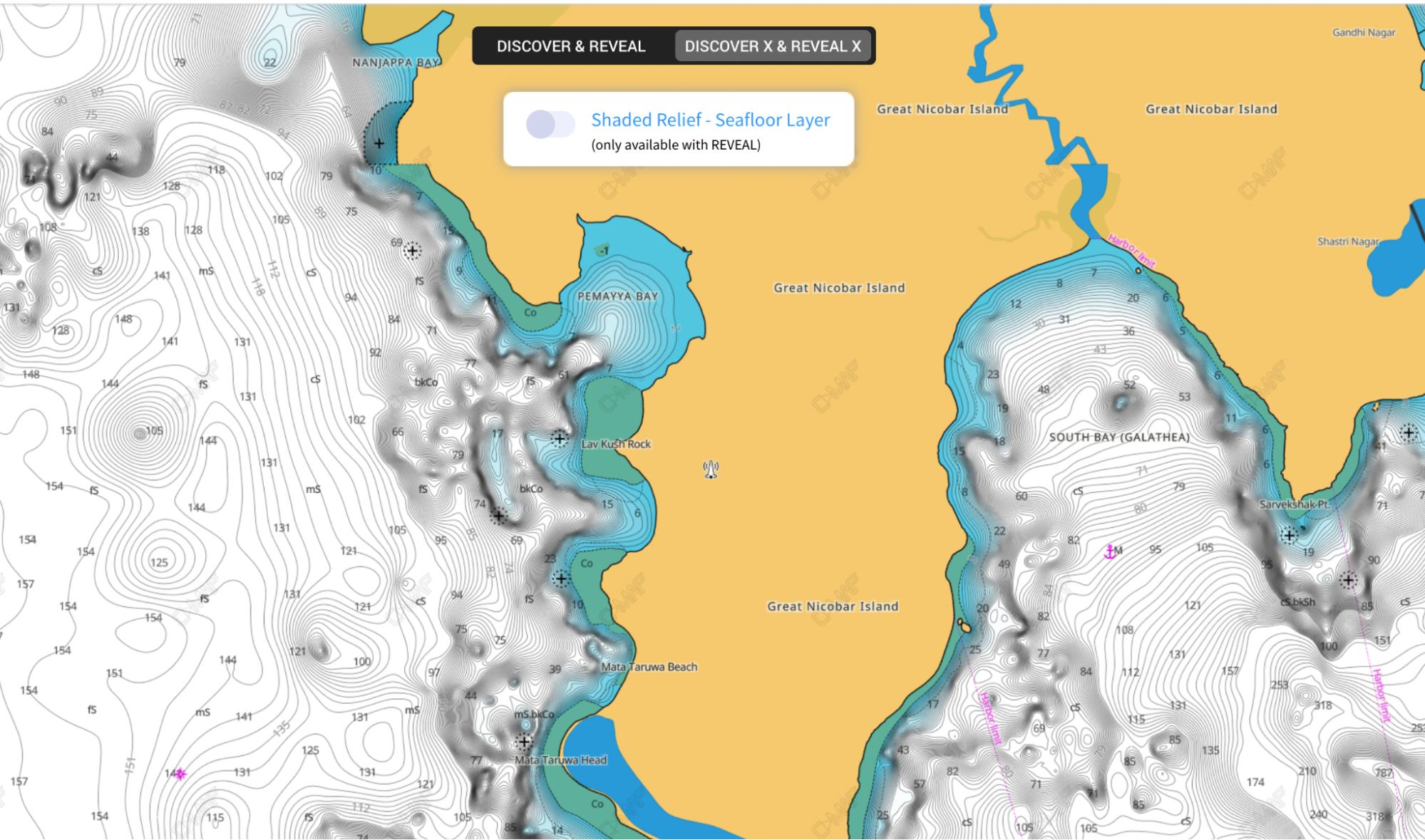

The 2021 land use map shows two coral reefs floating out in the ocean – a small one on the south-east coast, below Galathea Bay, and another, much larger one on the south-west of the coast. Scroll overlaid this map with a bathymetric map of Great Nicobar, which depicts the depth of the ocean at different points – we accessed this map from C-MAP, a website that maintains maps that are used for ocean navigation and fishing.

A comparison of the two makes clear that at the location of the smaller reef on the updated land-use map, the ocean is more than 80 feet deep. The larger reef is more sprawling – and while parts of the ocean where it is shown to be located are between 10 and 40 feet, most of this reef is shown to be floating in waters more than 60 feet deep.

Patankar noted that based on this exercise, the indicated location of coral reefs in the NCSCM’s updated maps was “not possible biologically”.

He recounted that the only time he had witnessed a dramatic change in corals around the Great Nicobar island was in 2005, a result of the 2004 tsunami. “Corals as big as a Maruti car were toppled and hectares of mangroves disappeared overnight,” he said. But he noted that “there has been no other incident that took place in the last few years” to explain the dramatic change in coral distribution between 2020 and 2021 that is depicted in the maps.

He added, “It looks like they did this to show that no corals are present here.”

Scroll emailed the NCSCM, Andaman and Nicobar Coastal Regulation Zone Authority, and the environment ministry, seeking responses to criticisms about the changes its maps recorded. This story will be updated if there is a response.

Other studies show presence of corals

Kothari’s submission to the National Green Tribunal also noted another major contradiction in official documents. Specifically, though the NCSCM’s latest map and study suggest that no corals exist in Galathea Bay, the project proponent’s own environmental impact assessment report, prepared by the Zoological Survey of India in 2021, noted that about 16,000 coral colonies would have to be translocated for the port project.

In fact, a 2022 book titled Faunal Ecology and Conservation of the Great Nicobar Biosphere Reserve, edited by the Zoological Survey of India and endorsed by the environment minister, Bhupender Yadav, stated that 33.45% of Galathea Bay had a “cover of live corals”.

Scroll spoke with a scholar who was formerly with the Zoological Survey of India, and had conducted diving trips on the island for their research. “If you were to ask me where corals are present on the island, I would mark the entire coast,” said the researcher, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of repercussions.

The researcher recounted that they had attended an early meeting about the upcoming project, at which they made a presentation to the Andaman and Nicobar administration, detailing findings about turtle habitats in the Galathea Bay and the area’s ecological importance. The researcher recounted that the officials at the meeting asked them to go through their slides quickly, and then suggested that if construction for the project proceeded, turtles could breed elsewhere.

“Since I know how they had been approaching this issue earlier, I do not trust them,” said the researcher. “This map seems completely fabricated to incorporate these plans.”

Scroll emailed the Andaman and Nicobar administration, seeking responses to the researcher’s account of this meeting and the administration’s attitude towards turtle habitats in Galathea Bay. This story will be updated if it responds.

We also emailed the Zoological Survey of India, seeking responses to the researcher’s account of this meeting, and the variance between the 2022 book’s documentation of corals and the NCSCM’s updated map. This story will be updated if it responds.

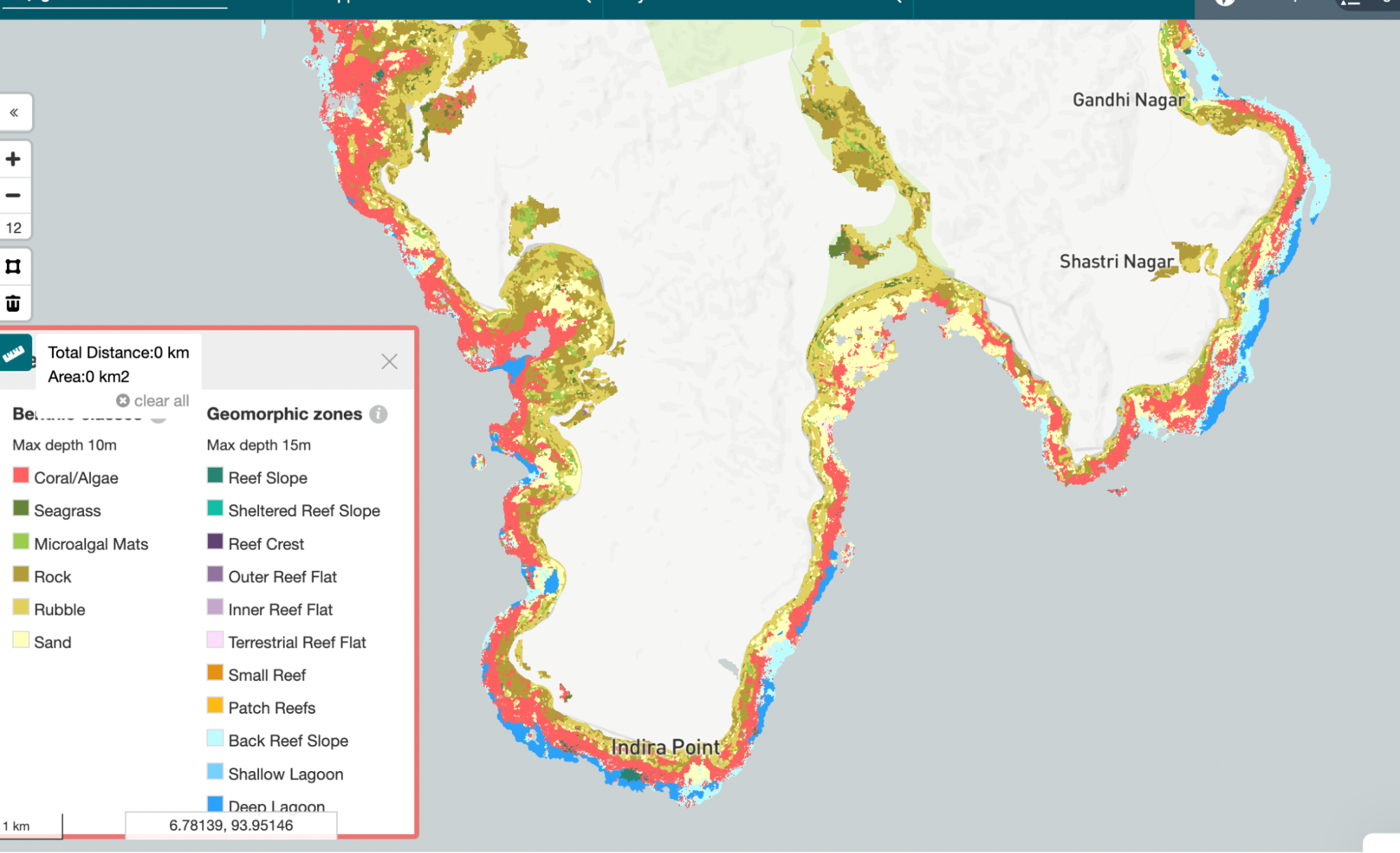

Other maps, created outside India, also show the presence of corals in the bay. One, called the Allen Coral Atlas, created by Arizona State University, uses high-resolution satellite imagery to map and monitor coral reefs across the world. A search on this map for the Great Nicobar island clearly shows the presence of reefs and algae in the Galathea Bay, as well as along the rest of the island’s coasts.

Other documents record change

It is not only in these maps that the NCSCM has recorded a dramatic change in the island’s protected lands.

In 2022, at the request of AECOM, a company hired by the government to conduct an environmental study of the Great Nicobar, the institute prepared a report to mark the island’s low tide and high tide lines, as well to indicate the parts of the upcoming project that would fall in different coastal zones of the island. In the document, the institute clearly noted that many parts of the project did fall in parts of the island that were in the IA category.

This included a 26-metre road as well as the port, both of which fell in nesting grounds of birds near two tribal villages adjacent to the Galathea Bay.

Apart from the mention of the port, the document also noted that work related to the “port reclamation area” and “port area” was also proposed on land that fell within the IA category.

More generally, it noted that the area that comes under the project includes and is surrounded by mangroves, corals and coral reefs.

But by the following year, the institute’s stand seems to have completely changed, as is evident from an affidavit that the environment ministry submitted to the National Green Tribunal.

In April 2023, while hearing the case challenging the project, the tribunal directed that a high powered committee be formed for “revisiting the environment clearance” of the project.

A person familiar with the case, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, explained that the committee had asked the NCSCM to conduct a site visit, after which the institute prepared another report on the island’s zones. This report is not publicly available, but in its affidavit to the tribunal, the environment ministry refers to this report, and stated that the NCSCM “concluded that no part of the project area is falling under the CRZ-IA area”.

Noting that these reports suggest that the government institute had taken two diametrically opposing stands on this question in the space of a year, the individual said, “Now, which report is right?”

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting