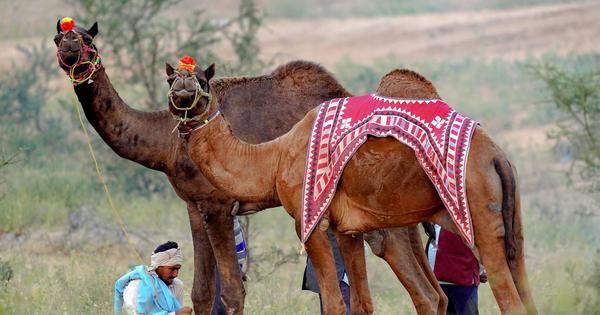

The annual Pushkar Fair in Rajasthan’s Thar desert is considered the largest camel market in the world. Camels are at the central feature of the fair at which livestock, including horses, cattle, goat and sheep, is traded during the week-long event, which began on October 30.

But the camel herds that once dotted the horizon of the desert state are becoming rare. In villages near Jaisalmer and Bikaner, herders say they now struggle to find grazing land and buyers. “Each of us used to have hundreds,” a herder from the Raika pastoral community in Bikaner told us in 2022. “Only a few have such numbers now.”

From an estimated 11 lakh in the 1970s, India’s camel population plunged by 75% to just 2.5 lakh in four decades, according to the 20th Livestock Census data released in October 2019. Between 2012 and 2019 alone, the camel population fell by 37%.

For centuries, the camel has been an ally for India’s desert communities – hauling water, carrying salt, tilling land, providing milk and sustaining human life in a landscape where little else survived or grew. The sharp decline in the camel population reflects the trajectory of a policy environment that has marginalised pastoralists, their economies and the landscapes that sustained their livelihoods.

The Draft Camel Policy Paper, released by the Department of Animal Husbandry and Dairying in September, calls this decline “a crisis of survival”. The policy proposes steps such as breed conservation and securing grazing rights. But will that be enough to save the ship of the desert?

Steady decline

For much of the 20th century, camels were essential for transport, as work animals pulling carts and luggage and for milk. Mechanisation later replaced camels in agriculture and transport, while canal irrigation and land conversion have shrunk grazing commons for herds.

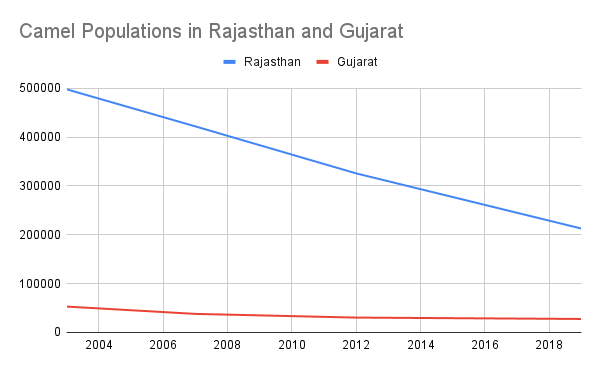

The decline in camels has been the sharpest in Rajasthan and Gujarat, which together hold nearly 90% of India’s camels. Rajasthan’s population has fallen to 2.12 lakh, while in Gujarat, where Kharai and Kachchhi breeds once thrived, numbers have dropped to just 27,620 as per the 2019 Livestock Census of India.

Measures aimed at increasing the camel population and safeguarding its cultural significance have had the opposite effect.

In 2014, the Rajasthan government declared the camel the state’s “heritage animal”. The following year, the Rajasthan Camel (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Export) Act, 2015 was passed to curb the inter-state transport and the sale of camels to slaughterhouses, with the aim of increasing its population.

But livestock keepers say the law disincentivised the keeping of camels, particularly male camels, which would be used as pack animals by Raika and Rabari shepherds to carry cots, household items and food rations during migrations.

In any livestock herd, there is a 50% chance that newborns will be male. Since only a few males are needed for annual breeding, most are sold – either for meat or, in the case of camels, to other pastoralists who use them as pack animals.

The ban on inter-state migration and sale for slaughter severely disrupted this trade. Animal welfare organisations say that camels are still indirectly being transported across states, eventually to be slaughtered for meat in states like Telangana. Though the ban was recently withdrawn, no notification has been officially issued yet.

Camels may no longer be as useful as they once were, but their importance endures.

Their ability to survive on minimal water and feed makes them vital for livelihood adaptation to the rising heat and changing climatic conditions across north-western India. They are low-impact browsers that feed on hardy shrubs, require little fodder or water and enrich the soil with their manure while their padded hooves prevent erosion.

The camel also reflects the trajectory of India’s pastoralism: from mobility and adaptation to a life on the margins. Pastoralist communities like the Raika in Rajasthan and the Maldhari of Kachchh have developed deep ecological knowledge of grazing cycles, drought management and breeding that has sustained biodiversity in some of India’s harshest terrains.

In Gujarat, herders of the Rabari, Fakirnai Jat and Sama Maldhari communities manage unique breeds such as the Kharai, which swim through coastal creeks to graze on mangroves. The camel is also tied to India’s cultural heritage, like in the case of Rajasthan’s Raika community for whom herding is a hereditary vocation as well as spiritual belief: they say Shiva created their community to care for camels.

Losing camels would mean the loss of a species and the living knowledge and cultural systems that co-evolved with the desert-dwelling animal.

Camel policies, economy

India had established the National Research Centre on Camel in 1984, but policy support has remained thin. Recognising the crisis, the Centre and state governments have begun designing responses.

Rajasthan, as part of its Camel Conservation and Development Mission, offers Rs 20,000 per camel calf born, insurance coverage and mobile veterinary camps. Gujarat runs a breeding centre at Dhori in Kachchh and annual disease-control programmes.

Similarly, the Draft Camel Policy Paper, released in September, proposes a National Camel Sustainability Initiative, the first coordinated national effort to address the camel population crisis.

Its proposal to promote the emerging camel milk economy is significant given that the camel population in Gujarat’s Kachchh district has been sustained by a growing market for camel milk.

Once limited to household consumption and whose sale was taboo, camel milk has emerged as a niche product with medicinal and nutritional properties. Yet, India produces close to 7,000 tonnes annually, less than 0.2% of the global output. Rajasthan and Gujarat have begun supporting this sector, through the Rajasthan Cooperative Dairy Federation and Sarhad Dairy, while brands like Amul are experimenting with camel milk-based products like ice creams and chocolates.

Though small, the camel milk industry holds potential for organic and free-range production and could expand exports to West Asia. Recognising camel milk as part of the formal livestock economy could also revalue pastoralism itself, acknowledging its ecological role and contribution to desert livelihoods.

The Draft Camel Policy Paper also outlines actions to:

● secure grazing rights and restore village commons (gochars);

● revive camel-based tourism and cultural fairs;

● promote breed conservation and youth training; and

● reform restrictive trade laws.

If implemented effectively, these steps can yield co-benefits for desert biodiversity and rural livelihoods beyond camel conservation.

Policy drawbacks

The draft policy’s major flaw is that it risks repeating a species-centric design by overlooking the interconnected nature of arid landscapes. Camels and the pastoralist communities who rear them, move across administrative boundaries for grazing and access to markets, therefore requiring conservation strategies that emphasise landscape-level coordination not just between departments, but also states.

The draft policy notes the need to ensure access to forage and grazing lands but fails to connect this to instruments like the Forest Rights Act, 2006, which could formalise grazing rights. In areas such as the Jamnagar Marine National Park and Kumbalgarh Wildlife Sanctuary, grazing restrictions have hurt herders, based on assumptions that camels damage vegetation. Restoration of gochars and the demarcation of existing grazing zones should therefore be a priority.

The draft policy acknowledges the importance of grasslands and open natural ecosystems, or ONEs, but must also address their accelerated conversion for large-scale renewable energy and infrastructure projects, as well as afforestation and plantation programmes which inadvertently restrict access for pastoralists and disrupt their migratory routes.

Across Rajasthan and Gujarat, grazing commons are being diverted for solar and wind parks, often without considering the ecological or social costs – a major concern for the Oran Bachao Andolan in Rajasthan, to save sacred groves.

For the camel to survive, its habitats must remain open, connected and accessible, aligning with ongoing community-led conservation movements in western Rajasthan, further grounding the initiative in the realities of land and community governance.

Finally, and crucially, pastoralists and livestock rearers must be adequately represented in the National Camel Sustainability Initiative. Without such inclusion, India risks repeating the mistakes of the Rajasthan Camel Act, which alienated the communities it aimed to protect.

Camels, climate future

India’s arid and semi-arid regions cover nearly one-fifth of its land area. As India looks to build a climate-resilient rural future, the camel is a symbol of endurance and adaptation.

With policy support, camel herding could anchor a climate-adaptive rural economy which values mobility, low-input production and ecological stewardship.

The National Camel Sustainability Initiative could reposition the camel economy within India’s broader climate-resilient development agenda linking traditional knowledge systems with modern markets. The recognition that conserving camels requires more than an animal husbandry approach is significant. Yet, the challenge lies in whether the policy can address the ecological and economic realities of India’s arid regions.

Aniruddh Sheth is the Research Coordinator at the Centre for Pastoralism, New Delhi. Sanjana Nair is a Policy Analyst at the Centre for Policy Design, Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting