By Binny Yadav

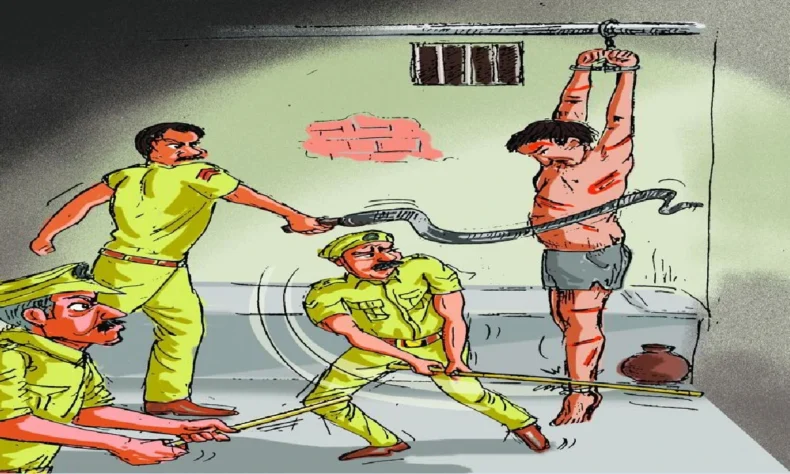

Why is it that every time there’s a death in police custody, the CCTV cameras are mysteriously “not working”? Coincidence—or a deliberate design? Behind locked station doors, away from public scrutiny, torture has long been suspected, but rarely proven. Post-mortems and medical reports provide fragments of truth, but when the moment comes for video evidence, the system fails, the footage vanishes, and the cameras are declared dead.

This September, the Supreme Court stepped in once again. A bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Sandeep Mehta, frustrated by repeated custodial deaths going unrecorded, floated the idea of automated surveillance—a control room that flags in real time whenever CCTVs go offline. “There seems to be no other way,” the bench observed, pointing to the futility of past directives.

RAJASTHAN’S SHADOW

The apex court’s urgency stems from a chilling trigger: a report of 11 custodial deaths in Rajasthan in just eight months, seven from Udaipur alone. Police attributed most to suicide or natural causes. But in case after case, families alleged torture—only to be told the cameras had “malfunctioned”.

One such case was that of Mohammed Rafiq, a 32-year-old daily wage worker who died within 36 hours of arrest. His post-mortem showed bruises and fractured ribs. Yet, no CCTV footage was available, despite earlier Supreme Court orders requiring 18 months of preservation. Oversight committees meant to ensure compliance hadn’t inspected the station in over a year.

JUSTICE DEFERRED BY DESIGN

The Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling in Paramvir Singh Saini vs Baljit Singh had mandated CCTV cameras in all police stations, CBI, NIA, ED, and NCB offices. Cameras were to cover lock-ups, corridors, entries, exits and interrogation rooms, with footage retained for 18 months.

Yet, compliance has been patchy. In Bihar, 61 percent of stations have non-functional systems. In Uttar Pradesh, 42 percent lack footage retention. Cameras exist, but often serve the police rather than the public: disconnected, disabled, or conveniently “offline” at critical times.

TECH VS CULTURE

The Court’s latest proposal—automated alerts and independent inspections—could reduce discretion, forcing transparency through digital logs and third-party oversight. Institutions like IITs may be roped in to design the system.

But legal experts warn that technology without accountability is toothless. Unless CCTV tampering is treated as evidence suppression, with liability fixed on station heads, the culture of impunity will persist. “No camera will make a difference unless there are consequences for turning it off,” one reformer observed.

Tragedies like the death of Suraj Kumar, a Dalit youth in Tamil Nadu’s Thoothukudi district this July, reinforce the point. His family alleged brutal beatings in custody. Once again, the station CCTV was “under repair.”

THE WAY FORWARD

The September 26 order could mark a turning point—if it shifts from expectation to enforcement, from soft directives to binding accountability. Automated monitoring will not end custodial violence, but it may strip away the cloak of invisibility that has shielded it for decades.

For now, too many of India’s police stations remain dark zones—where the state’s coercive power meets its most vulnerable citizens, and justice is deliberately obscured.

—The writer is a New Delhi-based journalist, lawyer and trained mediator

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting