“If it weren’t for love, people would get along fine. If it weren’t for love…”

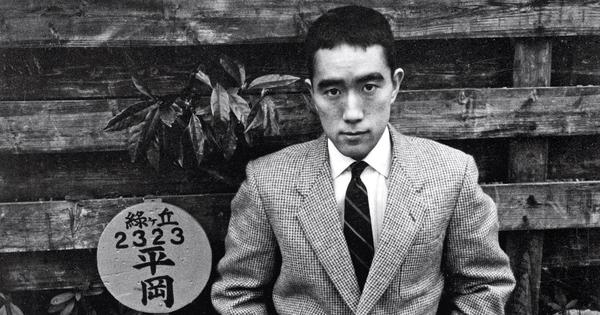

Yukio Mishima’s Thirst for Love is scandalous for all the right reasons. Written with startling clarity about a woman obsessed with a young man, Mishima forces the skewed power and politics of sex in Japanese homes to let itself be known. The novel almost seems to smirk at Japan’s socio-cultural traditions – comically stoic and punishingly refined – while animal emotions leap under its surface.

Loving in secret

Following the death of her philandering husband, Etsuko gives up city life and moves into her father-in-law’s home to live with her dead husband’s family. Even in his absence, she is bound to him – she must honour the chastity of widowhood and uphold the family’s good name as the eldest daughter-in-law. Away from all kinds of excitement, Etsuko experiences crushing loneliness – which is worsened by her lecherous father-in-law making advances on her. Hatred and disgust for the old man lead her to something even more sinister: Etsuko becomes infatuated with Saburo, an 18-year-old servant boy.

She takes to caring for him, going to great lengths to keep her affection a secret, without realising that neither Saburo nor anyone else at home suspects her of being up to something so audacious. Saburo, on his part, is oblivious to her desire, even thinking of her as the “ever-distant matron” of the house. She pursues him with the coyness of an inexperienced maiden, without realising that her tactics are so tame and outdated that it is impossible for a young man to read her actions as anything more than matronly. Meanwhile, Etsuko does not betray decorum and passivity while her infatuation reaches a feverish pitch.

Etsuko’s private tortures are exacerbated by her gossiping family members who notice how the father-in-law goes into her room or Etsuko takes longer than usual to tie his sash. Nasty rumours – not altogether untrue – float in the house and Etsuko is cornered. The patriarch, all-powerful that he is, remains unscathed. Mishima constructs an oppressive private life where abuse and desire go hand in hand. Her corruption is in stark contrast with Saburo’s youthful innocence – while Etsuko believes herself to be in love with him, Saburo cannot grapple with the enormity of even casual sexual relationships. Out on her own mission, one begins to suspect if Etsuko’s “love” has anything to do with Saburo, and if it is a twisted, fervent prayer out of the hell she has been lowered into.

She is uncharitably snubbed in a house where she is easily the most intelligent and resourceful. Saburo’s acceptance could be a vindication against her husband’s humiliation and her father-in-law’s vileness. Unable to really take matters into her own hands or break free of the customs that imprison her, Saburo’s new, young love could be the respite from the patriarchal quagmire she is in.

The way out

But men are not allies. Saburo’s youth is his fortune – he is indifferent to any torment simply by the virtue of not having lived long enough to experience it. Vapidness and lack of smarts make this otherwise dull, young man just the right person for Etsuko – it is onto him that she can freely project her desires and dreams, her fantasies and foils. The knowledge that Saburo will always be unattainable further emboldens her madness, gives her the vitality which she dearly desires.

The unfulfilled desire, the insatiable hunger, and the relentless thirst are essential to Etsuko’s survival. None of them must be quenched; the undernourishment and fatiguing masochism keep her from giving up when she has nothing to live for. In this continuum, the isolation and abuse come to fruit – all her suffering is worth it if she can have him, no matter how or when.

The endless chase, of which only she is aware, keeps her alert – she yearns for the elusive but must be careful to not touch it, she must perennially suspend herself between obsession and madness to live out her days as her useless husband’s widow and her degenerate father-in-law’s mistress. For Etsuko, the only way out is through.

Thirst for Love, Yukio Mishima, translated from the Japanese by Alfred H Marks, Vintage Books.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting