At a clothing store with a friend recently, she asked for my opinion on a dress. She twirled around to review every angle, the way the light caught the sequins, how the fabric fell in waves down to her ankles.

“You look,” I said sincerely, “enormous.”

To my subsequent befuddlement, this encomium was productive of rage rather than gratification. She pursed her lips, casting me a frosty glance, and collected the aforementioned waves of fabric before locking herself into the trial room. I couldn’t understand it. Where had I gone wrong? After all, I hadn’t called her fat. Hadn’t we been told, not so long ago, that the term “enormous” was much more palatable?

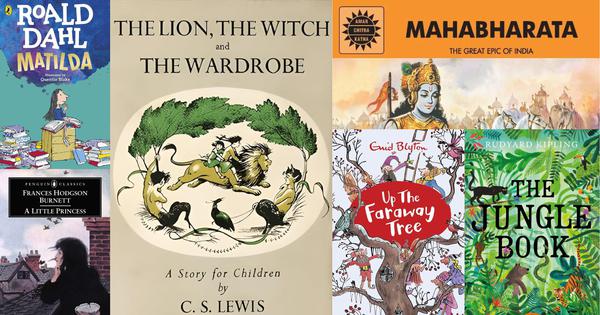

Of course, my friend isn’t a character in a Roald Dahl novel, so perhaps she missed that memo. It can be hard to keep up with all the memos. From the “racism, xenophobia and lack of literary merit” in Enid Blyton’s stories to the “racist and imperialist sentiments” in Rudyard Kipling’s work (per English Heritage) to the sexism of Judith Kerr’s picture books, there’s no end of criticisms to be levelled at classic children’s literature by those who are (probably smarting over) no longer (being) children. A document on how to analyse children’s books for racism and sexism contains no less than ten guidelines for this process, complete with multiple sub-guidelines and extra questions that every pre-adult reader is to be trained to ask themselves while also (presumably) trying to follow a story. Because obviously, as statistics show, getting children to read is too easy. But I digress.

Reading as children

Many of these criticisms likely hold some merit; after all, authors are a product of their time, and there is no doubt that the combined geological faults of racism, xenophobia and sexism have long caused fissures in the landscape of our societies. The temptation to take something once loved and pick it apart from a place of newfound enlightenment is hard to resist, perhaps as much a way to reassure ourselves about our own merit and maturity as to critique the merit of the work in question. It’s also really trendy. Unfortunately, the trend has become so all-pervasive that, in the midst of all this analysis and muckraking, we seem to have forgotten the beauty and treasures embedded in classic children’s literature, the invaluable lessons it contains, and the way it propagates other, more necessary stereotypes, such as courage, decency and honour.

I remember the thrill of being transported to different lands through the Magic Faraway Tree, replete with mischief and possibility, and the certainty that, in the end, every fix would be resolved by our young heroes and heroines through the employment of a little resource and a lot of gumption, two qualities that appeared essential for all of life’s challenges. After all, to quote another Blyton classic, “The best way to treat obstacles is to use them as stepping-stones. Laugh at them, tread on them, and let them lead you to something better.” The infamous Famous Five series is purported to perpetuate notions such as how girls are bound to do the cooking and domestic work while boys do the important stuff, but evidently my brother and I missed that memo, as all we gathered from the stories was that both girls and boys were equally equipped with the spirit of adventure and the capacity to set things right – and if anything, it was (girl) George whose wits often got them out of scrapes, whether it was putting a rude and inconsiderate houseguest in his place so he wouldn’t make extra work for Mrs Philpot or discovering the ship that got them off stormy Kirrin Island.

Beyond her most popular work, Blyton’s oeuvre also included a more serious title, Six Bad Boys, which dealt with juvenile delinquency. Far removed from the happy countryside families of her other stories, it is a tale awash with the smoke and grime of hard city living, a portrait of poverty and intense marital discord. Hardships at home galvanise the titular boys to look for a safe haven outside, and bonds that start off as simple friendship eventually turn them into a criminal gang, ending in harsh punishment. Blyton’s signature light touch doesn’t detract from the seriousness of the issues explored and her aim is clear in the author’s note: “Are you a child? Or are you a grown-up? It doesn’t much matter, with this book. It is written for the whole family, and for anyone who has to do with children. It is written, as all stories are written, to entertain the reader – but it is written too to explain some of the wrong things there are in the world, and to help to put them right.”

In this, she becomes an unlikely ally of Dahl himself, who firmly believed it was okay to write on darker topics for children, because children have the belief that no matter how bad things get, they will get better in the end – a belief we try to hold on to with increasing desperation as we age. Enough has been written about the travesty of neutralising the pungency and sharpness of Dahl’s writing in the newest editions, all the more ironic given that his stories were designed to illustrate the pungency and sharpness of life itself, and perhaps offer a cypher for how to deal with it, with equal sharpness, humour and, of course, a little magic. Let’s face it: we’ve all encountered a Trunchbull or two in our time, though likely (and unfortunately) not one bent on stuffing us with cake.

CS Lewis, in his magisterial Narnia series, is accused of promoting his admittedly Christian beliefs, but I’m not sure he actually managed to convert his readers to any religion except a worship of wardrobes. Aside from the fascinating worlds and characters he conjured, it is the universal salves of kindness, righteousness and faith that stand out in his stories, values that are as intrinsic to all religions as they are divorced from religion. The Pevensies, called upon to govern the newly-born realm, learn how to rise to the occasion and how to contend with challenges they were never prepared for, with grace and honour. They also learn that being selfish and insufferable might lead you to be turned into a dragon – a crucial life lesson for us all.

In another favourite, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess, the protagonist Sara Crew is forced to recalibrate her understanding of life when her father’s death leaves her penniless. Her indomitable spirit and generosity linger in the imagination far beyond the now-alien concepts of attics, lascars and dolls with wardrobes designed in Paris. She taught a generation of girls what being a “princess” truly means – not wearing “cloth of gold” (whatever that is) or being fussed over by fussy adults (hardly a malaise of the past) but conducting yourself with dignity and kindness, putting others first, regardless of circumstance.

The painful scene in which Sara, bitterly cold and literally starving, finds a four-penny coin in the snow and uses it to buy six buns – she’s hungry enough to eat twice as many – and then hands over five of them to another child on the street, even more emaciated than herself, became nothing short of canon. Surely there is no more sweetly profound and timeless lesson than this, that “if nature has made you for a giver, your hands are born open, and so is your heart; and though there may be times when your hands are empty, your heart is always full, and you can give things out of that – warm things, kind things, sweet things – help and comfort and laughter – and sometimes gay, kind laughter is the best help of all.”

The quote ties in well with another passage long etched in my memory. The boarding school story, best loved of all tropes, was dominated by Blyton and, of course, later, JK Rowling. I was never much of a Potterhead, preferring instead to immerse myself in the work of Angela Brazil, already out of print and out of fashion during my long-ago childhood, but holding irresistible appeal for me with her vivid descriptions of the Cornish moors. In the inventively-titled The School on the Moor, a visiting guest delivers a speech to the school, wherein he remarks that although he is certain the girls will go on to do great things as teachers, doctors, mayors – gasp, shades of feminist thinking! – the truth is that opportunities to do great, world-changing things are few and far between, and life is instead replete with chances to make small but impactful choices, which is why it is important to do “not one good deed a day, but every good deed that comes your way”. Another profound and timeless lesson.

Where we come from and who we are

Of course, a truly holistic exploration of classic children’s literature is beyond the scope of a short article – and probably even a long one – but there are examples littered through the archives, threaded between the lurid fairytales collected by Grimms and Perrault, the brutal but just laws of the jungle in Kipling’s The Jungle Book (as dissimilar to its Disney counterpart as to the Doordarshan version), and the charming obnoxiousness of Richmal Crompton’s William Brown. Closer home, the myths contained in our beloved Amar Chitra Katha comics, although sanitised versions of the originals, consistently reinforce the triumph of good over evil, even as the oral folklore of Nagaland and Meghalaya, esoteric if sometimes grisly, is passed down to each successive generation to maintain a record of where the community comes from and who they are.

Indeed, the best children’s literature does precisely that: it tells us where we come from and who we are. Sam Leith, in his seminal treatise The Haunted Wood, argues that children’s literature isn’t a defective and frivolous sidebar to the grown-up sort; it’s the platform on which everything else is built. GK Chesterton put it more simply; talking about The Princess and the Goblin, he stated, “It made a difference to my whole existence”. I look back on my own favourites, on the hours I have whiled away amidst the picturesque lakes of the Tyrol and the enchanted lanes of Prince Edward Island, with urchins, mountain girls and fairy-folk for company, drooling over creamy – always creamy – jugs of milk and thick – always thick – slices of toast, and I can’t help but agree. These are the stories that have shaped me and shaped the story of my own life. These are the stories I return to when life reminds me, once again, that magic and wonder are in short supply in the real world. I always find them there, a reprieve beyond price, and for that alone I will always be grateful.

Although the values contained within their pages may seem trite and naïve in adulthood, they carry kernels of sagacity in their simplicity. Would it, after all, be such a bad thing to live in a society pivoted upon honesty, decency and empathy? Imagine a world where politicians were on Scout’s Honour to fulfil their promises and abide by the law, where goodwill always outweighed personal prejudice, where Turkish Delight actually tasted good…ahem. Perhaps I am getting carried away on the wings of childish fantasy. But I must absolve myself of the most childish fantasy of all, that the evils we criticise classic children’s literature for are not still lavishly stippled across the world today. We haven’t outgrown them. We seem only to have outgrown the other things, the quaint, old-fashioned things we once believed built a quaint, old-fashioned thing called character. The sum, perhaps, of all the characters we’ve known and loved. And so I will continue to return to them, to these Neverlands where I find peace, where I know with certainty that, no matter how much the darkness of life gets me down, the light will always win.

Aishwarya Jha’s debut novel The Scent of Fallen Stars was published last year.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting