“During the late 1970s, I met this Arab lesbian who was born here … and she had a bruised eye. She had been kicked at a women’s bar by some White lesbians who called her a wog and kicked her out. She still has a deaf ear after that, and her spine is still not functioning.”

The violence contained in this memory is haunting. It is not the violence of the state, nor of men on the streets, but of those who were supposed to be allies – white lesbians in a women’s bar, policing through race. A space imagined as liberatory became exclusionary with the weight of colonial histories and racial hierarchies crashing down on queer bodies of colour. What remains is not only the survivor’s permanent injuries, her deaf ear, her damaged spine, but also the reminder that queer liberation has never been one singular story.

History shaped by exclusions

It is from such fragments of pain, resilience, and solidarity that Desi Queers: LGBTQ+ South Asians and Cultural Belonging in Britain, co-authored by Churnjeet Mahn, Rohit K Dasgupta, and DJ Ritu, begins to stitch together an alternative history. Instead of rehearsing familiar moments like the Stonewall riots in the United States or the miners’ strikes of the 1980s, this book turns our gaze toward the South Asian queers. Their lives complicate the tidy narratives of liberation we have inherited. They remind us that queer histories are always messy, intersectional, and shaped by multiple exclusions.

South Asian migration to Britain has been analysed for decades through the frameworks of colonialism, postcolonial displacement, race relations, and diasporic nationalism. But the stories of queer South Asians, of how they organised, resisted, built community, and shaped wider LGBTQ+ politics, remained conspicuously absent in both academic scholarship and mainstream queer historiography. Desi Queers steps into this silence with both tenderness and urgency.

At its heart, this book is about friendships, kinship, and chosen families; the intimate ties that sustained queer South Asians in hostile environments. But it is also about activism, archiving, and the insistence on acknowledging contributions that have been too long ignored. In re-centring queer South Asians within the story of queer Britain, the authors destabilise dominant narratives of both diasporic experience and queer resistance. They remind us that queer South Asians were never merely on the margins, but central to the making of cultural and political life in Britain.

When the conventional routes of knowledge proved to be inadequate, the authors of Desi Queers turned elsewhere. Public libraries, university archives, and official records offered almost nothing about the lives of queer South Asians in Britain. What does it mean when your history does not exist in the very places that claim to safeguard collective memory? For Mahn, Dasgupta, and Ritu, the answer was to look beyond the institutional, to open boxes tucked away in people’s homes, to pore through community-led projects, to listen to stories preserved in the fragile folds of memory. In these informal archives, the book finds its heartbeat.

Joy and flamboyance

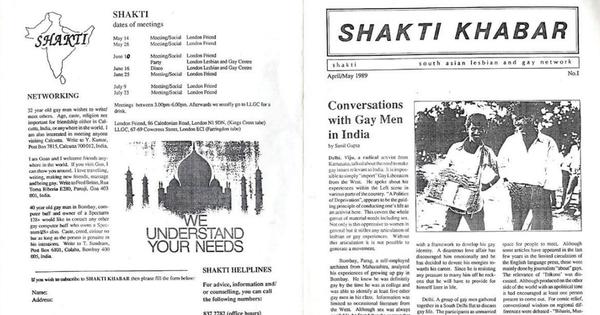

One of the most extraordinary discoveries was a complete collection of Shakti Khabar, the newsletter of Shakti, the first organisation of queer people from the Indian subcontinent in Britain, founded in 1988. Shakti was not just a political collective; it was a cultural refuge. It organised drag performances and parties, creating spaces of joy and flamboyance in an environment of hostility. It campaigned relentlessly on issues of racism and homophobia, offering queer South Asians not just safety but also a sense of belonging. The spirit of Shakti continues to reverberate today in institutions like the Naz Foundation, Naz Project London, and in Club Kali, the legendary London nightclub for South Asian queers that still thrives.

Yet, as the book points out, Shakti Khabar has rarely been acknowledged in the growing scholarship on queer print cultures. The newsletters are often excluded from catalogues and anthologies that claim to capture the vibrancy of feminist and queer publishing of the era. This absence is not accidental; it rather speaks to the layered exclusions that queer South Asians faced, not only within their communities and within white queer spaces, but also in the very spaces of cultural memory.

Practices of community-making are central to understanding marginalised groups, and for queer South Asians in Britain, the dancefloor became a site of both refuge and radical creativity. Spaces like Shakti Disco and Club Kali were not merely venues for entertainment; they were laboratories of identity, where Bhangra, Bollywood, and Hip-Hop fused into distinct aesthetics of liberation and belonging. Through interviews with DJs and organisational members, Desi Queers brings these spaces to life. DJ Ritu’s evocative recollection of being the first resident DJ at Shakti Disco underscores the delicate balance of joy and vulnerability that these communities navigated: the thrill of shared connection, the freedom to be oneself, shadowed always by the fear of exposure or attack.

Clubbing, however, was not universally sanctioned. Many first- and second-generation South Asians experienced parental restrictions, and even when they ventured into nightclubs, they confronted racism at every threshold, from the door to the dancefloor. Yet despite these barriers, a vibrant underground club culture flourished. In cities like London, Birmingham, and Bradford, daytime raves emerged as pragmatic solutions: spaces where young South Asians could celebrate their music and culture without parental censure, often occupying otherwise commercially “empty” hours.

The music itself was a radical act of hybridisation. Bhangra rhythms intertwined with Hip-Hop, Jungle, Garage, Reggae, Techno, and House, producing a soundscape that reflected both diasporic roots and contemporary British realities. These spaces were not only about cultural expression. They were politically and socially charged arenas where new forms of identity and solidarity were enacted. Crucially, they disrupted stereotypes about women’s roles in South Asian communities. Women like DJ Radical Sister (Rani Kaur) and DJ Ritu took their place behind the decks, asserting presence and desire in a space often coded as male. As one promoter recalled of the 1990s daytime raves:

“We would go to college in our traditional Salwar Kameez, then at Wednesday lunchtime we would get dressed into Western clothes in the toilets, do our makeup and head to the hall.”

Such transformations of halls, bodies, and rhythms were not mere performance; they were acts of community-making, of claiming visibility and pleasure in worlds that frequently sought to deny both. The book beautifully captures how these seemingly ephemeral moments, the spins of a DJ, the pulse of Bhangra beats, the sway of a crowd, were in fact central to the politics of belonging and the creation of queer South Asian culture in Britain.

Despite the landmark legal advances in Britain around LGBTQ+ rights, the realities of queer South Asians often remain untouched by policy. Racism in queer spaces, cultural exclusion, and pressures from family and community, the very struggles that Shakti and its members confronted decades ago, persist in various forms today. Desi Queers does more than recover a hidden history; it illuminates the networks of care, joy, and defiance that allowed queer South Asians to survive and thrive in the face of erasure. By foregrounding personal narratives, archival treasures, and the vibrancy of diasporic culture, from newsletters to dancefloors, the book models a methodology for studying marginalised lives: attentive, intersectional, and grounded in community knowledge.

Beyond its historical contribution, the book is a directional beacon for future research. It challenges scholars to look beyond institutional archives, to centre voices that have been silenced, and to interrogate the entanglements of race, sexuality, and migration in ways that are culturally specific yet globally resonant. For activists, historians, and cultural theorists alike, Desi Queers is a reminder that liberation is inseparable from belonging: that every act of remembering, documenting, and celebrating queer South Asian life is also an act of resistance and a call to imagine a more inclusive future. In this way, the book does not simply chronicle a past; it opens pathways for thinking about queer histories, identities, and communities yet to come.

Desi Queers: LGBTQ+ South Asians and Cultural Belonging in Britain, Churnjeet Mahn, Rohit K Dasgupta, and DJ Ritu, Queer Directions/Westland.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting