The spring of 1940 was a dispiriting time for the British people.

For the previous decade, the country’s leaders had tried to avoid a bloody, all-out war in Europe by acceding to Germany’s aggressive efforts to expand its territory. That policy of appeasement, as it was called, had broken down in September 1939, when Germany invaded Poland. Having committed themselves to assist Poland, Britain and France went to war with Germany. On May 10, 1940, the same day that Winston Churchill became Britain’s prime minister, Germany began an offensive against France by invading neighboring Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.

Using powerful blitzkrieg tactics, in which they delivered a quick, concentrated attack of tanks, infantry, and air support, the Germans overwhelmed Allied forces, trapping large numbers of troops in western France and Belgium. Miraculously, the Allies man- aged to evacuate hundreds of thousands of troops across the English Channel in late May and early June. This was the famous Dunkirk evacuation, a military feat that bolstered British morale and allowed the country to fight another day.

In this context, Churchill went to the House of Commons on June 4 and delivered one of the 20th century’s most memorable speeches. With Allied forces routed, he needed to rally his dispirited countrymen and steel them for a potential German invasion of the British Isles. Churchill did so with rousing rhetoric, proclaiming that “we shall defend our Island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender.” The speech, with its recognition of German victories, left some listeners depressed, but it inspired many others and even moved some to tears. Churchill’s secretary recorded in his journal that it had been “a magnificent oration that obviously moved the House.” One member of Parliament called it “the finest speech that I have ever heard.”

We often presume that the best leaders inspire courage by verbally evoking it at critical moments. John F Kennedy remarked of Churchill, “In the dark days and darker nights when England stood alone – and most men save Englishmen despaired of England’s life – he mobilised the English language and sent it into battle.” Great leaders in realms like sports or business make similarly potent attempts to speak courage into existence.

In his book Why Courage Matters, the late senator and war hero John McCain relates that the legendary college football coach Bear Bryant apparently prepared his quarterbacks to face their fears by following an important ritual. Before a big game, he would stride silently alongside the quarterback and then give them a single piece of counsel: to be brave. “During the course of a game,” McCain said, “Bear Bryant would have issued a hundred instructions to his quarterback. None of them could have been as important as his first. Be brave.”

As important as direct exhortations to bravery can be, the very presence of great leaders also can rouse followers to behave courageously. The most inspiring leaders seem to possess a force of personality that others find motivational – what we typically call “charisma.” Scholars have described the power of charismatic or transformational leaders to inspire followers to perform at their best.

Dating back thousands of years, the concept of charisma originally captured the idea of a “spiritual gift” or unique personal abilities that a divine creator bestowed on leaders to serve the public good. Drawing on these earlier notions, the 20th-century sociologist Max Weber conceived of a form of charismatic political authority grounded in a sense of a leader’s heroic personality. Charismatic leaders possessed traits that made them seem “supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional.” According to Weber, followers were so awed by these traits that they naturally paid deference to their leaders.

Scholars since Weber have observed how charismatic leaders inspire trust, confidence, and respect, all of which make people feel passionate about following them to take bold actions. These scholars have also set forth numerous theories of charismatic or transformational leadership, offering explanations for how charismatic leaders inspire performance. They have isolated traits that most people associate with charisma, including how “bold, colourful, mischievous, and imaginative” a leader seems to be.

But personal magnetism isn’t always such a great asset for a leader to have. Charismatic leaders can dazzle followers with their personal presence and inspire them to act, but they can also lead organisations astray because they fail at the more mundane, operational side of leadership. Further, they can become so central to organisations that they come to be irreplaceable. When they leave, rank-and-file members struggle to replicate what they believe made these leaders so great.

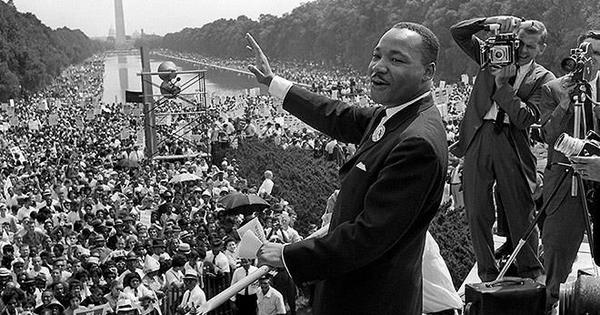

A deeper problem with the notion of charisma is its tendency to affirm popular myths about courage and the “great hero.” Whether regarded as a spiritual quality bestowed by the creator or simply a particular combination of personality traits, charisma seems to be the province of a few select individuals who were mysteriously chosen for greatness. Force of personality is a quality you’re born with – you either have it or you don’t. Famous speeches by the likes of Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, or Martin Luther King Jr play into this mystique of the heroic leader as a kind of prophet, one who wields a unique power to attract and galvanise. Still, there’s something about the right leader’s presence that does trigger in others a desire to take risks on behalf of a noble cause. When we experience someone as charismatic and wish to follow them, it’s ultimately because we perceive them as intensely competent and trustworthy. Many of us have experienced this ourselves: maybe it was that inspiring high school coach who pushed us to do more than we thought we could, or that manager at work who inspired us to raise our hand with an unusual suggestion.

Research supports a different, more inclusive way of thinking about charisma. It suggests that, like bravery itself, charisma isn’t a matter of personality but rather a result of underlying behaviours that any of us might cultivate. Great, charismatic leaders, in other words, aren’t just born; they’re also made through the right training. Instead of simply standing in awe of luminaries like Churchill or charismatic figures we might have met, we should ask ourselves: What do leaders like these do that allows them to have such a profound impact?

Scholars of leadership have singled out specific behaviours that motivate others to take action. Building on and refining these more specific dimensions of leadership presence, I’ve found that under many circumstances, leaders help followers take bold action by being in ways that create and sustain an aura of heroism around themselves individually and the group. Leaders I studied deploy three specific strategies for projecting their charisma. First, they craft and communicate a heroic quest in ways that followers will find clear and compelling. We’ve encountered heroic quests in Chapter 3, but here I discuss them from the leader’s point of view. Second, they encourage a personal devotion to the quest, modelling it and making their example accessible and relevant to followers. And third, once the quest is underway, they convey strength in the face of hardship, inspiring followers with their extraordinary sense of calm and encouraging them to stay committed.

Although these strategies have a step-by-step logic to them, leaders I studied sometimes engage with them out of order or in parallel. Regardless, adhering to these practices prompts these leaders not merely to preach the heroic quest but to live it to the fullest. Through their behaviour, leaders connect themselves so powerfully with the quest that followers perceive them as embodying it in their very person; in their eyes, the leader becomes the living, breathing form of what otherwise would be merely an abstract ideal.

Perceiving charismatic leaders as authentic exemplars of courage, and feeling more attached to the quest itself, followers aspire to become heroes themselves, a stance that leads them to surmount their fears and take more risks on behalf of the shared mission.

Excerpted with permission from How To Be Bold: The Surprising Science of Everyday Courage, Ranjay Gulati, Harper Business.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting