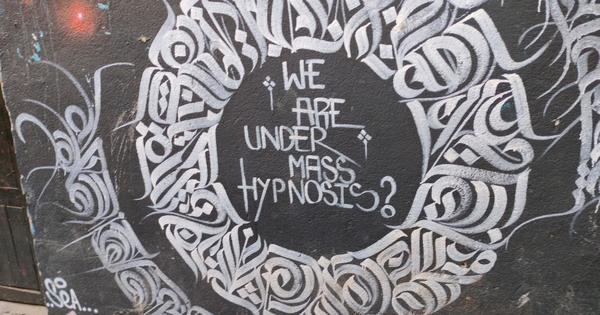

“We are under mass hypnosis?”

That was the question painted across a wall in Bhaktapur, a heritage town near Kathmandu, which I came across on a short visit to Nepal last year.

It was so unusual, I decided to turn back through the narrow red-brick lanes to take a photograph of it.

As protests recently swept Nepal this week, this piece of graffiti popped back into my head. It seemed to have been a portent of the tumult that led to the old order being swept away – even as a new one is waiting to be born.

On the face of it, the protests were sparked by a social media ban. But it’s clear that the demonstrators, mostly from the Gen-Z generation, born between 1997 and 2010, were actually upset with the corrupt state that had failed to meet their developmental needs.

Looking back, I realise much of my trip had circled around that very predicament.

Sixteen hours after landing in Kathmandu, we met our father’s friend, a retired officer of the Nepal Forest Services.

After talking about the scenic beauty of his country, he pointed to my sister and me, both in our late 20s, and added almost casually that there was “nothing for young people to do here”.

Both his children live abroad.

At first, I assumed he was speaking from personal experience. After all, his children had left Nepal after Class 12.

My sister is set to start studying at a university overseas later this year and I know how expensive it is to just survive in the West, even with a scholarship.

Nepal’s currency is weaker than India’s and yet middle-class families across the border seemed resigned to the idea that their children must leave if they wanted a future.

If Nepal’s middle-class residents believe that their children have to emigrate to find security, I wondered how the country’s poorer people were managing. How were they planning for their futures?

In the days that followed, bits of the answer were visible everywhere.

On the way to Nagarkot and in smaller towns like Bhaktapur and Panauti, billboards for services that could help young people study abroad were prominent.

Our cab driver, who had only studied until Class 12, told us that after finishing school, “everyone goes abroad”. It is estimated that between 17% and 20% of Nepal’s population lives outside the country – most of them young people. The money they send home constitutes about 24% of Nepal’s gross domestic product.

Our travel agent said that the best way to earn money in Nepal was not to open a restaurant or shop catering to local residents but to run a tour company with foreign clients.

In Nagarkot, a town to which visitors flocked to soak in the spectacular views of the Himalaya, owners of even shops asked us to pay in Indian currency for something as ordinary as fruit. Despite the perception that New Delhi is patronising at some times and a meddling bully at others, Nepalis still prefer the “Big Brother’s” currency, a young woman whose family ran a small supermarket told us.

In Kathmandu, my sister’s friend, a topper from Mumbai’s Tata Institute for Social Sciences, told us that her salary as a teacher in a private college was only 25,000 Nepali rupees per month. (around 20,000 Indian rupees).

Comparisons between India and Nepal are not straightforward.

India’s economy is much larger, its institutions more developed and its federal fiscal system cushions its poorer states. But the parallels are hard to ignore.

As we drove through a market on the outskirts of Kathmandu, I was reminded of the small town of Shivpuri in Madhya Pradesh.

There were the same bustling markets, the same stark divisions between affluence and want, the same sense of young people with few options but to leave.

To me, Nepal’s story is not one of failure but of unfulfilled promise. Its youth are talented, its diaspora resilient, its geographical location strategic. But policy, politics and investment have failed to converge to create opportunities at home.

Last week, Nepal’s young people decided that they’d had enough. They took to the streets to demand a system that would address their problems.

In India, however, even as the deeper questions of employment, inadequate education and healthcare, and economic equity remain unaddressed, we have been lulled into a fog of communal divisions and xenophobia.

The question on that wall in Bhaktapur is just as relevant on this side of the border.

Also read:

‘There was no hope’: What sparked the violent protest in Nepal

A reminder: India’s democracy is its greatest shield against a Nepal-style revolution

Here is a summary of last week’s top stories.

Proving your identity. The Supreme Court directed the Election Commission to accept the Aadhaar card as the 12th document to establish identity for inclusion in Bihar’s revised electoral roll. It was not among the 11 documents that the poll panel had initially listed for applicants to be included on the roll. This had drawn criticism from petitioners, who described the decision as being “absurd” because Aadhaar is a document that is most prevalent.

On Monday, the court said that while an Aadhaar card can be produced as a valid proof of identity, it is not proof of citizenship. It also directed the poll panel to verify the authenticity of the Aadhaar cards submitted.

A West Asian security quagmire. Israel struck a building housing some leaders of the Palestinian militant group Hamas in Doha on Tuesday. The attack put the Gaza ceasefire and hostage release talks at risk as Qatar has been a key mediator in the negotiations.

Hamas claimed that its top leaders survived the Israeli attack, but six others were killed. This included at least one Qatari security official.

Doha described the attack as a blatant violation of international law, and said that it will “not tolerate this reckless Israeli behaviour” and the disruption of regional security.

The strike was a “wholly independent” operation by Tel Aviv, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office claimed after the attack.

Qatar is a major ally of the United States and hosts one of the largest American military bases in the region. Washington is also an ally of Israel and acts as a guarantor of the country’s security.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi issued a statement saying that India condemns the violation of Qatari sovereignty, but did not mention Israel.

Defamation suit. A Delhi court directed NDTV journalist Gargi Rawat to pay Rs 10,000 as damages to commentator Abhijit Iyer-Mitra for “liking” an allegedly defamatory social media post. The commentator had filed the suit in 2019 against advocate Dushyant Arora, who wrote the post, and Rawat.

While he had sought Rs 20 lakh in damages, the court set the fine at Rs 10,000, saying that Iyer-Mitra himself was “no stranger to controversy” and had often made “objectionable, derogatory and reprehensible comments” on social media.

In a separate case, the Delhi High Court on Wednesday refused to grant immediate interim relief to Newslaundry journalists, who claimed that Iyer-Mitra had made additional defamatory comments about them on social media on July 3 and August 4, despite being ordered to take down previous posts that they deemed offensive.

Also on Scroll last week

Follow the Scroll channel on WhatsApp for a curated selection of the news that matters throughout the day, and a round-up of major developments in India and around the world every evening. What you won’t get: spam.

And, if you haven’t already, sign up for our Daily Brief newsletter.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting