The democratic landscape of South Asia is marked by paradoxes, contradictions and a stubborn endurance. It is a region where democracy has been repeatedly imperilled – by fascistic majoritarianism, military authoritarianism and theocratic repression – yet never fully extinguished. From theocratic autocracy in Afghanistan to illiberal populism in India, and from the military–industrial stranglehold in Pakistan to the dynastic–authoritarian episodes in Bangladesh and the Maldives, the subcontinent today confronts a formidable spectrum of democratic decay.

Nevertheless, across time, every country in the region has, in its own moment of reckoning, resisted total collapse into autocracy and struggled back towards democratic renewal. This recurring democratic instinct – however faltering, however compromised – speaks not only to the political vitality of the region’s peoples, but to the unfinished nature of the democratic experiment itself.

South Asia also offers an unparalleled laboratory for the comparative study of democracy and governance. The region presents nearly the entire typological range of political regimes: the complex federal democracy of India; Pakistan’s enduring entanglement between civilian rule and military dominance; theocratic fascism under Taliban rule in Afghanistan; the transformation of Bhutan and Nepal from monarchies to constitutional democracies; and the episodes of outright dictatorship, dynasticism and electoral manipulation in Bangladesh, the Maldives and Sri Lanka.

These overlapping and often colliding trajectories offer a rich, real-time canvas through which scholars, policymakers and citizens alike can witness democracy in motion – not as an ideal state of affairs, but as a contingent, conflict-ridden and deeply human pursuit of dignity, representation and justice.

The South Asian experience offers the world a compelling set of democratic lessons born not of stability, but of struggle. It reveals how democracy can take root in societies marked by poverty, illiteracy, social hierarchies and violent conflict – conditions often thought inhospitable to democratic norms. It shows how institutions, even when battered, can recover through civic resistance, electoral innovation and political improvisation. Perhaps, most importantly, it cautions against complacency by reminding global democracies that authoritarianism does not arrive suddenly, but through slow erosion – against which vigilance, reform and inclusive governance remain the only durable safeguards.

But any portrait of democracy in South Asia, no matter how wide its frame, remains incomplete unless it turns inward – towards the hierarchies that structure daily life and delimit the boundaries of political participation.

Caste is not just a social category in South Asia – it is a system of governance. It shapes who gets to lead and who must obey, who has a voice in public institutions and who is silenced even before they speak. Across the region, we have seen how caste and its equivalents – whether defined explicitly as in India and Nepal, or more obliquely as through biradari in Pakistan or occupation-based exclusion in Bangladesh – still determine whose lives are protected by law and whose lives are invisible to it.

No account of democracy in South Asia is complete without grappling with this foundational hierarchy. Electoral victories, constitutional provisions and party-based mobilisation have all made some room for caste-marginalized groups, but the deeper structures – land, labour, access to justice and public respect – remain largely unchanged.

The way forward is not a mystery. Every country in the region already has laws, provisions or past reform efforts that could (if taken seriously) begin to shift the balance. But political will has been absent. Caste is treated as a social issue when it is, in fact, a political structure. Reform will require direct action: enforcement of anti-discrimination laws, redistribution of land and economic opportunity, independent monitoring of representation in public institutions, and investment in education, health and housing for historically excluded communities.

These are not gestures of charity – they are the unfinished tasks of democracy. Until caste no longer determines where one sits in a classroom, what job one is allowed to do, or how one is treated by a police officer or a judge, democracy in South Asia will remain partial – technically functional but morally hollow.

Yet, even as caste operates as a subterranean architecture of exclusion, another, more institutional form of distortion plays out within the very entities meant to advance representative politics: the political parties themselves.

One of the most urgent but least acknowledged obstacles to democratic renewal in South Asia lies within the parties themselves. While much attention is paid to elections, institutions and leaders, far less is asked about how those leaders are chosen, how dissent is treated or whether parties are open spaces or closed fortresses. As discussed at length earlier, the region’s parties often concentrate power in the hands of the few, sidelining internal dialogue and insulating leadership from accountability. This hollowing out of internal deliberation weakens not just the parties, but the very capacity of democracy to evolve, to respond and to include. In the absence of internal checks, parties risk becoming vehicles for ambition rather than institutions of public trust.

However, it is within these same spaces that some of the most necessary reforms must begin. Building more democratic societies will require building more democratic parties: ones that listen before they command, renew rather than replicate and welcome challenge instead of fearing it. Reforming internal party structures is not a technical fix – it is a political struggle, one that calls for courage from those in power and imagination from those outside it. The legitimacy of the democratic project in South Asia will depend, in part, on whether political parties can learn to democratize themselves – not out of pressure but out of conviction.

Of course, parties do not operate in a vacuum. Their health, and the vibrancy of democracy at large, depends also on the ecosystem of ideas, dissent and debate that surrounds them – an ecosystem increasingly under siege.

In South Asia, the story of democracy cannot be told without reckoning with the forces that shape, distort or silence the public conversation. The media – once trusted to question authority and hold power accountable – has increasingly become a terrain of capture, fear and illusion. Whether through economic monopolies that erase editorial independence, legal frameworks that criminalize dissent or digital landscapes awash in disinformation, the region’s information ecology has become dangerously fragile. This matters not simply because journalists are under threat, but because citizens are slowly being cut off from the facts, debates and stories that enable democratic choice. When trust in media collapses, what collapses with it is the very idea of a shared civic world – one in which people disagree, deliberate and decide with clarity and dignity.

Looking forward, the future of democracy in South Asia will depend in no small part on whether the region can rebuild that civic world – through plural, independent and fearless media. This requires more than legal reforms. It demands political will to dismantle the architecture of propaganda, courage to confront digital authoritarianism and investment in public institutions that protect the integrity of information. But it also calls for imagination: new models of journalism rooted in community, new platforms that centre marginal voices, new solidarities that cross borders and languages. If democracy is to mean more than the ritual of elections, it must reclaim its soul in the realm of public discourse. That reclamation begins not with silence or compliance, but with the courage to speak – and to listen – again.

If the crisis of public discourse narrows what can be said, the politics of exclusion narrows who gets to speak in the first place. This is seen nowhere more starkly than in the treatment of ethnic minorities across the region.

The future of democracy in South Asia will be defined as much by how it treats its margins as by how it conducts its elections. Across the region, ethnic minorities have borne the weight of historical grievances, administrative neglect and majoritarian nationalism. Their exclusion is not merely a policy failure – it is a democratic failure, one that hollows out the very promise of equal citizenship and political voice. When ethnicity becomes a reason for suspicion rather than a claim to recognition, when belonging is determined by conformity instead of history, then the democratic ideal ceases to be plural and begins to calcify into something narrower, harder and more brittle.

Restoring democracy to its fullest meaning will require more than procedural fixes – it will demand a shift in political temperament. Power must be reconceived not as something to be defended from difference but as something strengthened by it. The region’s constitutional frameworks must open wider – accommodating not only the presence of diverse ethnic communities, but their right to shape the terms of political life. This calls for courage to relinquish control where it has been hoarded, to decentralize where centralization has failed, and to imagine new compacts of solidarity across lines of language, land and memory. Without that, South Asia’s democratic future will remain confined to its formalities, never fulfilling its far more urgent task: to make room for every story, especially those long kept at the edge.

Just as democratic inclusion must be reclaimed in society’s margins, so too must it be defended at its procedural core: the very institutions entrusted with safeguarding the integrity of elections.

In South Asia, the electoral commission stands not only as a procedural organ but as a mirror of the state’s democratic intent. Where these bodies function with integrity, independence and courage, they lend credibility to the entire democratic enterprise. Where they falter – through passivity, political capture or public distrust – the damage runs deeper than flawed elections. It erodes faith in the idea that power can be transferred peacefully and fairly. This is particularly significant in a region where electoral contests are often the only legitimate outlet for deep social, ethnic and regional fault lines. When the referee is believed to be compromised, the game itself is seen as rigged, and the ground beneath democracy begins to crack.

Going forward, what South Asia’s democracies require is not merely electoral reform, but reimagination on an institutional scale. Election commissions must be structurally shielded from executive manipulation and financially empowered to act without fear or favour. Their leadership must reflect the diversity of the populations they serve, and their actions must speak transparently to citizens who have grown weary of staged fairness.

But more than rules and budgets, what these institutions need is moral courage – an ethic of guardianship that sees democracy not as a sequence of events, but as a promise made to the people. That promise must be renewed not only through periodic elections, but through the daily labour of building institutions that are principled, transparent and quietly resilient in the face of political pressure.

However, even the most independent electoral institutions cannot fulfil the democratic promise if the arenas they safeguard remain exclusionary. Nowhere is this more evident than in the enduring marginalisation of women from the very spaces where decisions are made.

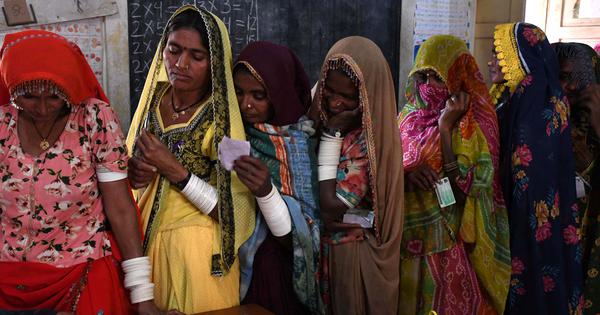

Across South Asia, democracy remains lopsided as long as half the population continues to be treated as political afterthoughts. Gender equality in representation is not merely a question of fairness – it is a test of the democratic promise itself. When women are under-represented in parliaments, political parties and public institutions, what is lost is not just their voice, but also the possibility of a more just and responsive politics. The persistent exclusion of women from decision-making reflects how power still clings to patriarchal assumptions about leadership, credibility and authority. A democracy that does not allow women to lead, legislate and dissent on equal terms is not just incomplete – it is compromised.

Nevertheless, the future need not be a simple extension of the present. The fact that women, when given the opportunity, win elections at higher rates than men is not just statistically notable – it is politically instructive. South Asia’s democratic renewal must begin by dismantling the structural and cultural barricades that keep women out: party gatekeeping, the unpaid burden of care work, violence and intimidation, and the myth of political ‘unwinnability’. Reforming electoral systems, embedding accountability within parties, and investing in economic and educational access for women will require more than policy tweaks – they demand political courage and moral clarity. A region that has produced formidable women leaders must now make room for millions more – not as exceptions but as equals.

But representation is only one face of the democratic crisis. Alongside who gets to participate lies the equally urgent question of who is allowed to contest, and how the normalization of impunity has come to haunt the electoral arena itself.

Excerpted with permission from Democracy’s Heartland: Inside The Battle For Power in South Asia, SY Quraishi, Juggernaut.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting