When copies of Gillian Tindall’s book, City of Gold: The Biography of Bombay, first made their way to Mumbai bookshops in 1982, they must have taken the city by storm. Two generations of readers had been waiting for a Mumbai biography – the previous one having been published as far back as in 1949. Sweeping in its scope, Tindall’s biography charted the growth of the city over three centuries. Though the narrative stops around 1900, it is peppered with her observations on how Mumbai grew in the twentieth century and her speculations about the possibilities for the city in the coming decades.

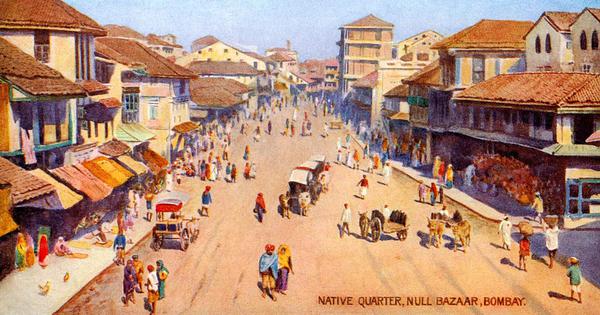

Profusely illustrated with images of bygone Mumbai that were inaccessible in the pre-internet era, it was also a visual treat for its readers. As a photographic archive of Mumbai in 1980, the book is unique. There is a whiff of colonial nostalgia in the book, but most Mumbaikars, expert at holding their breath on its odoriferous streets, could sidestep those passages.

For many Mumbaikars, it is the first book they had read on the city. Sidharth Bhatia, whose own biography of Mumbai was published earlier this month, recalls his first encounter with City of Gold: “When I saw the book at the Strand Book Stall, I immediately grabbed a copy that I still treasure,” he said. “Its distinctive cover [a colour lithographic print by Jose Maria Gonsalves] depicted a city whose buildings were familiar but whose denizens had changed beyond recognition. I would roam Mumbai clutching it in my hands like a guide book to learn more about the streets I grew up in.”

Though it was aimed at a general audience, the book has became an important text for historians and researchers. The historian Dinyar Patel remarked, “Tindall’s book was one of the first books I read on the history of Bombay – recommended by a great-aunt of mine as I was just getting interested in doing a PhD in Indian history. The more I do my own research on the city, the more I appreciate the work and detailed research it entailed. While it mostly hews to a European narrative of the early city, City of Gold remains an invaluable source on Mumbai’s early centuries.”

Gillian Tindall’s books exploring the history and context of places and communities have had a lasting impact on urbanism and the way architects work for nearly 50 years #ribajprofilehttps://t.co/Og0UJHABOu pic.twitter.com/lZPvcNqNSz

— RIBAJ (@RIBAJ) May 16, 2023

Gillian Tindall joined a list of illustrious city biographers with her Mumbai book, a lineage going back 200 years of which she was scarcely aware. She could not have known of Mahomed Ghyasoodeen who wrote the first biography of Mumbai, Jaan-e Mumbai (The Soul of Mumbai), in Persian in 1817. Nor does she seem to be aware of Govind Narayan’s 1863 Marathi biography, Mumbaiche Varnan (An Account of Mumbai), a landmark Mumbai publication. Or the 1867 Gujarati book Mumbaino Bhomiyo (A Guide to Mumbai) by SD Dewanjina.

George Buist, who wrote the first definitive account of the city in English, seems to have eluded her since his biography is embedded in the Bombay Calendar and Almanac for 1855.

Tindall is on familiar territory with later biographers – JM Maclean, James Douglas, SM Edwardes – and writers such as Samuel T Sheppard, DE Wacha , RP Karkaria and the duo of AD Pusalker and VG Dighe, the authors of the aforementioned 1949 biography published on the occasion of the All India Oriental Conference in Mumbai.

She came to urban biography by a rather circuitous route. An architect by training, Tindall began her writing career in 1959 as a novelist. She went on to write biographies of novelists and somewhere along the way, she metamorphosed into an urban biographer. Her books on Paris and London are as celebrated in those cities as City of Gold is in Mumbai. Why she chose Mumbai as a subject is not very obvious but its strong colonial connections and nineteenth-century architecture, on which she lavishes a lot of attention, must have been a big draw.

She had done extensive research on the city before she first arrived in Mumbai in the late ’70s, having read most of the books on the city and many of its nineteenth-century newspapers.

In Mumbai, Gillian Tindall could enter spaces which later city historians would struggle to enter. For instance, she notes that the house of Mahomed Ali Rogay, one of the founding partners of the opium trading firm of Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy & Co, “is still there in the crowded Bhendi Bazaar, in Nakhoda Mohulla – ‘Captain’s Ghetto’ – and is still occupied by the Rogays. I have been inside it.” When I tried to do the same a few years ago, I failed.

She also had access to material which no longer exists: “I have also been privileged to read and quote from an extensive collection of MS [manuscript] notes and cuttings, mostly unattributed, compiled by JRB Jeejeebhoy.” While editing Jeejeebhoy’s writings on the city, I tried to locate them but in vain.

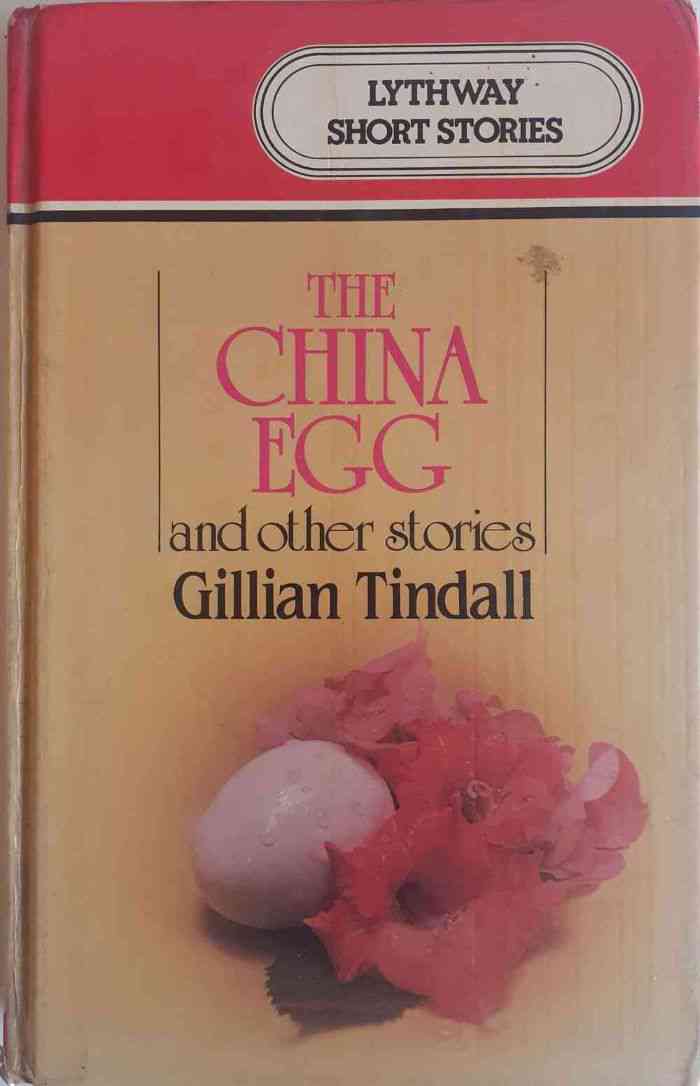

It is generally unknown that Gillian Tindall wrote not one but two books on Mumbai, the one as obscure as the other is celebrated. Published in 1981, a year before City of Gold appeared, it is a novella titled The China Egg, which tracks the quest of a childless English lady who comes to Mumbai to adopt an Indian baby.

Deftly melding fiction with travel memoir, Tindall fills the narrative with all that not could not be included in the biography. She slips in historical references to the Wadia shipbuilders, recently-demolished mansions in Mazagon and the fort at Sion. There are rides “in a slow, jolting, stopping train, through Bombay’s endless northern suburbs,” a visit to the Sewri cemetery on a red BEST double-decker bus, and dinners “in restaurants and clubs too grand to be bothered by the permit rules on alcohol”. The tone for both the books is set by her first sight of the city:

“Some kind of lichen-encrustation becomes visible on the hillside now slanting beneath the ’plane’s wheeling turn, but it is not lichen but a colony of insects or rodents, and then not rodents but human beings, living in shanties clinging to the hillside only a few hundred feet below, with no more connection with the deafening monster above them than if they were on another planet. You crane your neck in dread to see a battered toy lorry unloading metal pipes, a tiny oblivious woman carrying water, a child squatting by a chain-link fence, an old man scurrying from destruction as the very grasses within the ’plane’s widening shadow began to shiver and bend – and then, suddenly, with a bump like Alice landing on dry sticks at the bottom of the rabbit hole, you are down on the tarmac, taxiing in the engine’s decelerating roar, the vision and dread are gone and you are part of this other world yourself and must come to terms with it.”

Gillian Tindall not only came to terms with the city but also made many enduring friendships. The bookseller-turned-film critic, Rafique Baghdadi first met Tindall during her first visit to the city when she, with the Parsi actor Minoo Chhoi in tow, walked into the Jaico Publishing bookshop where he worked. Modest to a fault, Baghdadi matter-of-factly states that “Gillian taught me how to look at buildings.”

The regard must have been mutual since a copy of Tindall’s numerous books, each accompanied by a custom-designed postcard, found its way into Baghdadi’s library. He was not the only Mumbaikar with whom she kept in touch for four decades and more. City historian Foy Nissen was another friend who had contributed a few excellent photographs of contemporary Mumbai to City of Gold. When Nissen’s collection was broken up after his death in 2018, the Tindall books, unavailable in most Mumbai libraries, made their way to the Asiatic Society of Mumbai.

Gillian Tindall was the author of nearly 40 books encompassing fiction, memoir and history in a literary career spread over sixty-six years. Her last book, a novel titled Journal of a Man Unknown, was published posthumously in November 2025.

Mumbai was merely a whistle stop in this journey, a city she returned to every decade or so but never wrote about again. When we were putting the final touches to my first book, Govind Narayan’s Mumbai, in 2007, my publisher in London, Anthem Press asked me if I would like anyone to write a foreword. The first name I thought of was Gillian Tindall but, as it happened, she was rather preoccupied just then and turned down the invitation.

Was Gillian Tindall’s visit in 1979-’80 a catalyst in the revival of local history and heritage conservation in Mumbai? Surely, it is not just a coincidence that the person whom she singled out in the acknowledgements of City of Gold, Father John Correa-Afonso of St. Xavier’s College, founded the Bombay Local History Society in 1979.

Wouldn’t it be appropriate if the Society were to commemorate her association with the city by instituting an annual Gillian Tindall Memorial Lecture on urban biography and history?

Murali Ranganathan is a historian and translator.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting