By Sujit Bhar

In a landmark verdict with far-reaching implications for the country’s tribal communities and India’s environmental jurisprudence, the Supreme Court judgment concerning the Saranda forest in Jharkhand has emerged as a powerful precedent for how India can balance conservation imperatives with the constitutional and statutory protections granted to forest-dwelling communities.

Delivered by a bench led by outgoing Chief Justice of India BR Gavai and Justice K Vinod Chandran, the ruling does far more than simply ban mining within one kilometre of protected areas or direct the notification of Saranda as a wildlife sanctuary. It establishes, unequivocally, that the rights of tribals and forest dwellers do not—and cannot—extinguish merely because an area is declared a wildlife sanctuary.

This shift, embodied in the Court’s interpretation of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 (WPA), and the Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA), is of profound national significance. It widens the legal imagination beyond Saranda and sets into motion a constitutional ethic that protects tribal rights—not as temporary allowances, but as enduring entitlements intrinsic to India’s identity as an ancient cultural civilisation.

For decades, the dominant bureaucratic and political narrative has painted forest-dwelling communities as “encroachers” on land that rightfully belongs to the State. This judgment turns that logic on its head. Citing Section 24(2)(c) of the WPA and Section 3 read with Section 4(1) of the FRA, the Court reminds the State that tribals are not intruders in forests—they are rightful owners, custodians, and continuing inhabitants whose rights survive even after the State invokes its sovereign power to declare wildlife sanctuaries.

Section 3 of the FRA protects a wide spectrum of rights—habitat rights, community rights, rights to live on forest land, conversion of leases, and access to forest resources. Section 4(1), with its non-obstante clause, elevates these rights above conflicting laws. The judgment emphasises that even in cases where certain rights may need modification—as in critical wildlife habitats—FRA’s Section 4(2) imposes rigorous safeguards and procedures.

This interpretation will reverberate well beyond Jharkhand. It sets a precedent for every wildlife sanctuary, national park, tiger reserve, and conservation zone in India: tribal rights are not to be sacrificed for conservation, development, or private profit. They are central to all three.

THE DEVELOPMENT VS PEOPLE NARRATIVE

A striking element of the judgment is its unambiguous dismissal of the state’s argument that declaring Saranda a sanctuary would displace villages, destroy infrastructure, or harm local livelihoods. The bench calls this claim “a figment of imagination,” noting that the collector and chief wildlife warden have statutory powers to accommodate all continuing rights.

By asserting that tribal habitations and community infrastructure do not have to be removed to make room for conservation, the Court punctures the long-standing myth that development projects or ecological protections must necessarily override tribal rights. Instead, it demands that the State “educate the tribals/forest dwellers” about the rights they possess—a sharp reminder of the paternalistic governance systems that have kept tribal communities disempowered and uninformed.

This is revolutionary. For decades, bureaucracies have weaponised the rhetoric of “national interest” to justify displacement, whether for mining, dams, or wildlife sanctuaries. The Supreme Court now flips the script: the State must prove that any restriction is valid, rather than assuming that tribal rights are expendable.

The Court’s observations on Articles 48A and 51A(g) of the Constitution are crucial. Environmental protection is not merely a policy choice; it is a constitutional mandate for both State and citizen. Yet, the judgment refuses to allow “environmental protection” to become a euphemism for corporate extraction or bureaucratic arbitrariness.

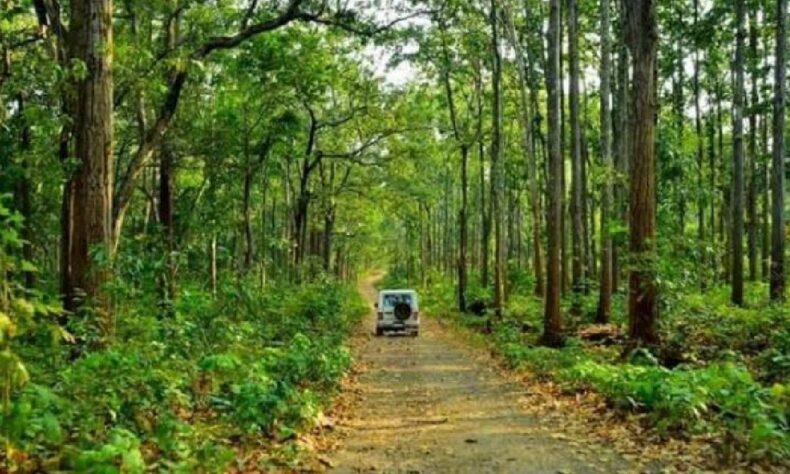

Saranda, an ancient Sal forest with rare and endangered species—including the critically endangered Sal Forest Tortoise—is one of India’s ecological treasures. But, it is also home to indigenous communities, whose cultural, spiritual, and economic existence is intertwined with the forest.

The apex court, recognising this duality, reasserts the principle of sustainable development, rejecting the Jharkhand government’s shifting stands on the extent of the sanctuary area. It highlights inconsistencies: having first admitted that no mining or diversion occurred in the 31,468.25 hectares notified in 1968, the state subsequently attempted to shrink the sanctuary to 24,941.64 hectares, before at one point even claiming it could expand the sanctuary to 57,519.41 hectares.

POLITICAL AND CORPORATE INFLUENCES

Such erratic decision-making raises uncomfortable questions about political influences, mining interests, and bureaucratic motivations. By cutting through these manoeuvres, the top court sends a clear message: conservation areas cannot be redrawn to suit private or political interests.

Perhaps the most consequential impact of this judgment lies in its ability to act as a shield against predatory capitalism. Tribal lands in India have long been the first casualties of mineral greed. From Niyamgiri in Odisha to Hasdeo Arand in Chhattisgarh, mining giants have eyed the forests that tribal communities depend on.

Saranda is no exception. It sits atop vast iron ore deposits, making it a hot spot for mining activities and corporate pressure. By banning mining within one kilometre of protected sanctuaries, nationwide, and directing that Saranda’s forest compartments be almost entirely declared a wildlife sanctuary (with only six mining-related compartments excluded), the Court has effectively erected a legal wall between tribal habitats and extractive industries.

Moreover, the judgment reiterates that ancillary activities by entities like the Steel Authority of India may continue only insofar as they comply with FRA and WPA protections. The rights of people come first; minerals come second.

This precedence is crucial in a world where capitalist development models view forests as resources to be monetised, not ecosystems to be nurtured. The Court’s message is clear: India’s development cannot be achieved at the cost of its first peoples.

UPHOLDING INDIA’S CULTURAL LEGACY

India is one of the oldest continuous civilisations in the world, and tribal communities are among its most ancient inheritors. Their knowledge systems, ecological practices, and spiritual traditions constitute a living archive of pre-industrial, sustainable living that has survived millennia.

By declaring that tribal rights survive even in wildlife sanctuaries, the Supreme Court recognises that traditional knowledge systems are not threats to biodiversity—they are its greatest protectors.

From the sacred groves of the Western Ghats to the agro-forestry traditions of the Northeast, tribal communities have been living embodiments of ecological stewardship long before modern conservation laws existed.

This judgment elevates that reality into jurisprudence. It affirms that:

- Tribal culture is not an obstacle to conservation;

- tribal habitation does not harm wildlife;

- tribal rights are not negotiable in the face of corporate or state interests.

This is essential for preserving India’s intangible heritage. Tribal traditions, languages, rituals, and relationships with land form the backbone of India’s ancient cultural identity. To protect these communities is to protect the civilisation itself.

The apex court’s directives provide a framework that could transform India’s governance of Scheduled Tribes and forest dwellers:

- Mandatory state-wide recognition of FRA rights when conservation zones are notified.

- Public communication, ensuring tribals know their rights.

- A model of sanctuary governance that does not involve eviction or displacement.

- Judicial oversight to prevent states from altering conservation boundaries for political or commercial motives.

This is a departure from the colonial legacy of forest administration—where land was seen as property of the State and forest dwellers as transient occupants. The Supreme Court affirms that India, as a post-colonial democracy, cannot replicate the extractive governance models of the past.

MORE THAN A LEGAL DECISION

The Saranda judgment is more than a legal decision; it is a moral and civilisational statement. It places tribal rights not at the margins of Indian law, but at its centre. It recognises that conservation without people is hollow, development without consent is unjust, and capitalism without checks is dangerous.

At a time when forests are shrinking, mining pressures are rising, and tribal cultures face existential threats, this judgment charts a new path. It shows that India can honour its ancient traditions, uphold constitutional promises, and pursue sustainable development—without succumbing to the greed of unregulated capitalism.

Most importantly, it signals that the future of India’s forests will not be dictated solely by corporations or governments, but also by the communities that have lived in harmony with these ecosystems for thousands of years.

In this sense, the Supreme Court’s Saranda judgment is not just a legal milestone—it is a reaffirmation of India’s soul.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting