On a late August evening in 1938, five doctors assembled at Jinnah Hall in Bombay’s Grant Road area to attend a public meeting chaired by the poet and independence leader Sarojini Naidu. In just over two days, these doctors would board a ship at Ballard Pier, embarking on a long journey to China, a nation enduring what its people called the “War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression”.

Naidu, while fastening Red Cross bands to their arms, did not mince words: “You are undertaking a dangerous task…some, or one of you, may not return.”

The men – members of what would be remembered as the Indian Medical Mission – were fully aware of the risks. Yet, as a 28-year-old doctor chronicling the voyage wrote, their anxieties were outweighed by the pride they felt taking part in an act of “internationalism and anti-imperialism”.

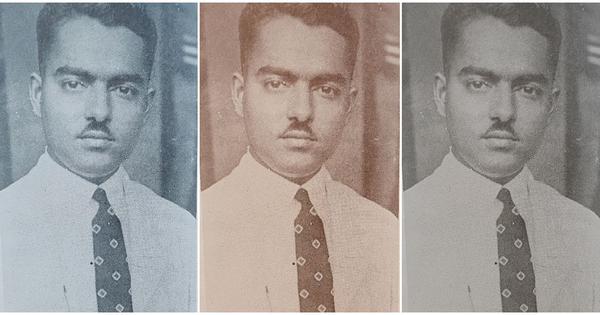

That young diarist was Dr Bejoy Kumar Basu, whose notes would, many years later, become the book Call of Yanan: Story of the Indian Medical Mission to China 1938-1943.

Signs of solidarity

In 1937, as Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China, the Chinese military commander General Zhu De sought help from Jawaharlal Nehru and the Indian National Congress, requesting them to send medical supplies and surgeons. Nehru, a committed Sinophile, took the request to his party, which set to work, forming a committee to collect funds and select medical volunteers for China.

The reach of the committee’s appeal extended far beyond India: responses came from places as far as Mauritius, Kenya, Syria and the United Kingdom. Ultimately, over 700 people answered the call, including 100 doctors.

The committee, raising Rs 35,000 (about Rs 2.4 crore today), selected a core team led by Dr Madan Mohan Lal Atal, a veteran of the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, an organisation supporting Republicans against General Franco’s nationalist regime in the Spanish Civil War. Joining Atal on the mission were deputy leader Mohanlal Cholkar, Basu, Debesh Mukherjee and Dwarakanath Kotnis, whose early death in China would later make him the most remembered member of the group.

On September 1, 1938, a crowd gathered at Ballard Pier to watch the doctors depart, with Sarojini Naidu herself joining to bid the group farewell. “Chinese vice-consul with his wife and a large contingent of Chinese boys and girls garlanded us, enthusiastically singing their national anthem ‘Chi Lai….,’” Basu wrote. “Dr. Kotnis was so heavily garlanded that nothing was visible except his weary but exultant face.” The Indian mission carried its own medicines and equipment, while a truck and an ambulance for its use in China were dispatched from the United States.

Even en route, the doctors encountered heart-warming displays of solidarity. In Colombo, an enthusiastic Chinese store owner took a photo with the group in front of his shop. In Penang, a “welcoming mass of people”, predominantly overseas Chinese and Indians, garlanded the doctors. After that, “with their leaders, we motored to the Chinese Association Hall in Acheen Street, where a public ovation was awaiting us,” Basu wrote.

Singapore was much the same, with large crowds at the pier waving Indian and Chinese flags while shouting “Vande Mataram” and “Chi Lai”. In Hong Kong, too, they were greeted with cheers and applause.

Grim introduction

Upon arriving in Canton, now Guangzhou, the doctors were graciously hosted by Soong Ching-ling or Madame Sun Yat-sen, later a vice president of the People’s Republic. Revered today as the “Mother of Modern China”, she welcomed the Indian group by throwing a banquet in their honour, where she went out her way to make them feel comfortable.

“Madame Sun Yat-sen observed our clumsiness in handling chopsticks,” Basu wrote. “Fearing that we would remain famished, she dipped her hand into the chicken in front of her and exclaimed ‘God has given fingers to pick up food,’ and began to eat. We gratefully followed her example.”

In Canton, the Indian doctors witnessed bomb craters and shattered buildings – a grim introduction to the war’s toll on the country. To safeguard them from Japanese bombardment, the Red Cross facilitated their onward journey to Changsha in Hunan province.

“Seven heavily loaded trucks with military and medical supplies, a hundred metres apart with a pilot car ahead, cautiously drove forward in a cloud of dust through sharp bends in the hilly track,” Basu wrote. “Dangerously narrow and unpaved road; very beautiful scenery of hills, villages and brooks; many trucks, accidentally fallen in the gorges, lay in grotesque positions down below.”

After stopping in Changsha, the team proceeded to Hankow in present-day Wuhan, where they were integrated into Curative Unit 15 of the Chinese Red Cross. This incorporation marked their official role within the Chinese medical relief efforts during the war.

Basu and Cholkar formed one surgical team, while Kotnis and Mukherjee made up another. Atal worked as a general physician.

The spirit of international support was palpable in Changsha: volunteers from the United States, Europe, Russia and even Java joined a banquet hosted for the Indians by Ye Jianying, the chief of the Eight Route Army, the larger of the two communist forces that fought the Japanese. Among those at the banquet was the writer-journalist Agnes Smedley, an ardent supporter of Indian independence.

“General Ye started with a toast to the independence of India, and set the tone for the two and a half hour long dinner,” Basu wrote. “Song followed song in different languages sung by different nationals – the Eight Route Army Marching song, ‘Crossing of the Yellow River’ song, ‘Russian Air Force’ song. Miss Smedley astonished us by singing Vande Mataram. I had to sing Nazrul’s march song in Bengali – ‘Chalre Chalre Chal’. Everybody appeared to enjoy it because of its militant rhythm.”

Yet, the relentless stress and strain of the war took their toll. Basu recalled frequent quarrels with Atal, the mission chief, which escalated into a fistfight just before Atal’s departure for India. Their last disagreement revolved around safety concerns: after 21 months in China and with Cholkar and Mukherjee having already returned home, Atal was leaving too and wished for Kotnis and Basu to accompany him. However, the two young doctors stood firm. They ignored his fears for their lives, choosing to stay on in China, despite the risks.

There was also a simmering distrust between the Chinese communists and nationalists, who had fought a bloody civil war before uniting to resist the Japanese invasion. In 1941, this tension erupted into a violent six-day conflict known as the South Anhui incident, when nationalist forces attacked the Communist New Fourth Army in Anhui province. The clash nearly reignited civil war, weakening the united front against Japan. As a committed communist, Basu naturally aligned with his comrades.

During this time, Basu developed a close friendship with Kotnis, and together their efforts extended beyond treating the wounded. When crossing enemy lines, they would actively sabotage infrastructure used by the Japanese, including railway tracks.

“Several fighters from the irregular guerrilla unit armed with saws, went out to cut the telegraph poles,” Basu wrote. “Suddenly we found a highway ahead of us. We ran across the enemy communication line. Hardly had we run for 2 li [1 kilometre] when the hell of rifle and cannon fire started. Our flank guards were prepared for it and replied, suitably hidden in the gullies.”

The Chinese resistance to Japanese aggression was fuelled by the support of rural peasants. Basu described how many peasants “gave their huts to the 8th Route Army, where several hundred patients, medical staff, and operating rooms were accommodated”. “In the vicinity of enemy areas, the patients and hospital workers put on peasant dresses” he added. “When the enemy comes, the peasants help to cart the wounded to neighbouring villages. The more sick, who cannot be transported, are comforted by the women folk, who come forward and claim the men as their brothers or sons or husbands who got injured by stray bullets, while working in the fields.”

When the Indian doctors met General Zhu De, they engaged in a lengthy discussion about the Chinese struggle against Imperial Japan and the Indian independence movement. The Chinese general suggested that India’s best path to independence lay in mounting a violent uprising against British rule. “Dr. Kotnis and I agreed with this view that conditions in India were similar to China in many respects and for our liberation, we might have to wage this kind of war against imperialists,” Basu wrote.

Meeting with Mao

Basu wrote about the times when they met leaders such as Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong, who mostly lived in caves during the war. When they met Mao for the first time, the revolutionary expressed gratitude to the Indian National Congress and Indian people for their sympathy and aid.

“He recalled the traditional friendship that existed for millennia culminating in anti-imperialist solidarity,” Basu wrote. “In the old times Buddha preached his liberal religious sermons to usher peace in all lands under heaven, the present Indian Medical Mission had come to China to preach the message of anti-imperialist unity of the people.”

Mao was keen to know more about “anti-Fascist, anti-Imperialist Indian leader Nehru,” whose name in Chinese was pronounced as Nihelu. He also asked about “Kanti” (Gandhi) and told the interpreter to explain that Kanti literally meant “sweet earth” in Chinese.

Basu recounted Mao’s opposition to Gandhi’s non-violent struggle against the British. “He warned us that among the imperialists, the British were the most cunning and experienced, so we would have to navigate a very difficult and critical path.”

The senior members of the mission disagreed with Mao. “During these discussions, our deputy leader, old Dr. Cholkar, a strict Gandhian but also a Hindu communalist, became agitated and said ‘under Mahatma’s leadership, we will get our independence,’’’ Basu wrote. To this, Mao replied that revolutionary violence was needed to counter reactionary violence from the British.

Members of the mission were excited about Nehru’s visit to Chongqing in August 1939 and hoped he would visit their unit in Yanan, but that was not to be.

Humiliating treatment

After Kotnis died in 1942, Basu remained the sole member of the Indian Medical Mission in China. He stayed on until July 1943, before flying from Chongqing to Kunming, then on to Assam, and finally Calcutta.

He wrote of the “eternal snows” covering the Himalayan peaks as his plane crossed into India and recalled a kind Chinese air hostess who wrapped a blanket over both of them to keep warm in the freezing Dakota aircraft.

“For the first time in many years, I saw my compatriots, the dark skinned, big eyed and big nosed Indians with skinny legs going about the airport serving us food,” he wrote. “The sultry weather reminded me that I had come to my homeland.”

Upon landing in Calcutta, Basu was taken to a security control office behind the Great Eastern Hotel, where British and Indian officers subjected him to a “gruelling search and interview”, even threatening to imprison him under the Defence of India rules.

“So I was back in my motherland, where this humiliating treatment is usual for Indians,” he wrote. “Later I learnt they were all armed because they were afraid I might be an agent of Subhas Chandra Bose, now in Singapore.”

After his return, Basu became a full-time worker of the Communist Party of India. In 1944, he assisted Khwaja Ahmad Abbas and V Shantaram in making a film about his close friend Kotnis.

In 1958, Basu travelled to Beijing to study acupuncture and went on to establish the first clinic using this Chinese medicine technique in Calcutta. He died at age 74 in October 1986.

In August 2025, the Chinese government honoured BK Basu with a commemorative medal for his invaluable contribution to aiding the people of China during the war.

All images courtesy BK Basu’s personal archives.

Ajay Kamalakaran is a writer, primarily based in Mumbai. His Twitter handle is @ajaykamalakaran.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting