Stephen Greenblatt (b 1943) is one of the most influential American literary historians, and a central figure in modern humanities scholarship. He has served as the John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University since 2000. The cornerstone of his legacy is his role as the primary architect of New Historicism, a theoretical approach that fundamentally reshaped literary criticism in the 1980s and 1990s.

The New Historicist methodology demands the reading of “sub-literary” and non-canonical documents side-by-side with “great works”. Greenblatt and his colleagues often prefer the term “cultural poetics”. This preferred terminology emphasises the poetics – the generative, creative act – of cultural systems. Cultural poetics focuses on how expressive acts, including art, are actively made up or generated alongside “other products, practices, discourses of a given culture”. This framing moves the inquiry beyond simple reflection, positioning literature as an active participant in the construction and negotiation of cultural meaning.

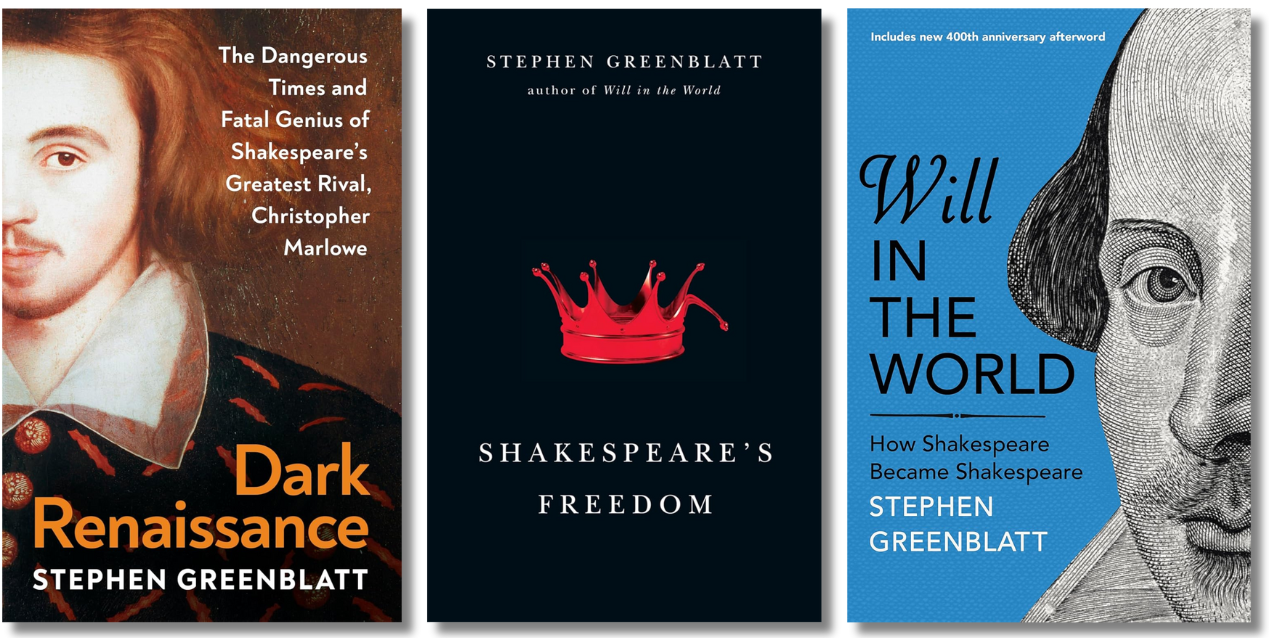

Greenblatt’s later work achieved significant crossover appeal, securing his status as a major public intellectual. His book The Swerve: How the World Became Modern earned him the 2011 National Book Award and the 2012 Pulitzer Prize. Similarly, Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare spent nine weeks on the New York Times bestseller list.

In a conversation with Scroll, Greenblatt framed his career not as moving away from theory, but as a deliberate synthesis, defining his legacy by the successful integration of specialised scholarship with broad public engagement. He offered a vigorous defence of the Humanities’ enduring relevance, arguing that their vitality depends on rigorous interdisciplinary collaboration and methodological innovation. Excerpts from the interview:

Reflecting on your distinguished career, how has your thinking about the relationship between literature and culture evolved since your early work like Renaissance Self-Fashioning, and what unified vision do you hope ultimately defines your legacy?

When I was an undergraduate at university, the overwhelmingly dominant approach to literature and culture was via New Criticism, which I had a deep immersion into. We were told that we shouldn’t be interested in anything outside the text. I remember reading Alexander Pope and coming across an extremely misogynistic and unpleasant reference to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. And I said, “Who is Lady Mary Worley Montagu?” I was told that wasn’t a relevant question.

In the 1960s, after I graduated from Yale, I went to Cambridge on a grant, and one of my teachers was a scholar named Raymond Williams. I’d never encountered a Marxist, nor had I encountered anyone before who had a powerful, vital sense of a world outside the text. That vital sense had a huge influence upon me. When I returned to graduate school and to Berkeley to teach, it seemed crucially important to read the texts and understand the world in which they were participating. This did not seem to me a betrayal of literature but quite the opposite. What I always wanted to do was love the work, care about it, and understand it better. And I still feel that way as I look back on my 50-year career.

Could you elaborate on the relationship between your intellectual journey and your scholarly work? How have facets of your personal background or lived experience informed your theoretical preoccupations and choice of subjects?

My love for Shakespeare started fairly late. I remember being 13 years old and having my junior high school teacher teach As You Like It, and I hated it. I thought this was the worst thing I’d ever encountered. But then somewhat later than that, still in high school, I had a teacher who taught us King Lear, which is a crazy thing to teach high school kids. What I most remember is that this incredibly wise teacher once said, “I don’t understand a certain portion of the play”. And none of my teachers had ever said that. And the fact that there was an enigma that he couldn’t understand had a powerful effect on me for reasons I can’t explain. As an undergraduate, I did not take a Shakespeare course, and as a graduate student, I wrote on Ralegh, not on Shakespeare. And yet Shakespeare is like the enormous planet Jupiter, and it just slowly pulls everything that’s floating around closer and closer to the centre.

Has literature lost its relevance today?

I don’t think that literature has lost its relevance, but it is morphing – as it has always done – into new forms.

What role do you think interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation can play in revitalising the Humanities and demonstrating their ongoing relevance and importance?

Much of my own teaching and at least some of my writing – such as my recent book Second Chances: Shakespeare and Freud – has been collaborative. And even when my writing is not collaborative, it reflects work I have done with colleagues. Thus, with Joseph Koerner, my art historian colleague at Harvard, I taught several graduate and undergraduate courses. The work from those courses helped to shape my book The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve.

Can you discuss your approach to teaching and mentoring students? What do you think are the key elements of effective pedagogy in the Humanities?

Walter Benjamin, the great German critic, said, “Every monument of civilisation is a monument of Barbarism”. If you look hard at Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, you realise it’s complicit in horrendous colonial acts in Ireland, but you must love the poetry simultaneously. Understand that if you don’t have an aesthetic appreciation or if you simply hate it, you’re missing nine-tenths of what matters.

I want to tell my students, “I want you to have some reason to believe that the works are worth spending time with.” When you love them, you and others will feel some resonance inside you while reading them. It’s also difficult to have your mind in two or three places simultaneously, but that’s the whole point. It’s a point that goes back to the Iliad or the Odyssey. The works of art that most matter put you in this uncomfortable position of having your mind in multiple places simultaneously.

How do you respond to critics who argue that New Historicism prioritises historical context over the literary text itself/texts themselves?

My teacher, Harold Bloom, called Shakespeare God. He attacked what I was doing because he said I was the Chief of the School of Resentment. But I don’t hate the works. I love them, but I also want to understand what they’re complicit in.

In your book The Swerve, you explore the impact of Lucretius’s De rerum natura on Western culture, arguing that Lucretius’s ideas about the natural world and human existence had a profound impact on Western culture. In your view, what were the most salient impacts? What drew you to this topic, and what do you think are the implications of this work for contemporary society?

The immediate occasion that led me to write The Swerve was an academic conference I attended in Scotland. The assignment was to write about when an ancient work returned to circulation. I had discovered Lucretius’ De rerum natura in translation when I was a student at Yale. The paperback cover had a provocative painting by the surrealist Max Ernst, and I bought it for 10 cents. A poem about ancient physics does not seem ideal for summer reading, but I did end up reading it, and I thought about how it radically suggested a secular worldview, including a universe made up of little atoms. So, at the conference, I chose to think about the person who recovered Lucretius’ poem, and I thought, who’s this odd book hunter, a papal secretary? He seems to be a very strange character.

Muddasir Ramzan is an academic and writer from Kashmir. He holds a PhD in English from Aligarh Muslim University. His forthcoming novel will be published by Bloomsbury.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting