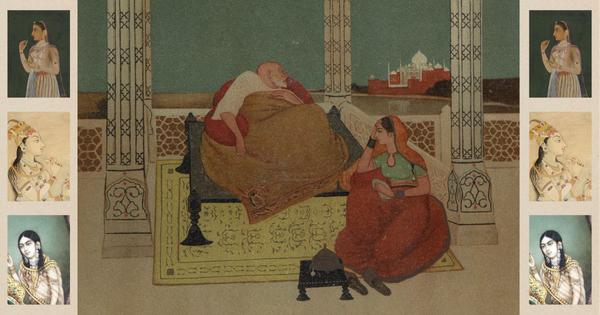

By the time Shah Jahan lay dying on that cold January day in 1666, he would have known that he had been forsaken by all the men in his family. ‘I can indeed barely repress my indignation,’ spluttered French physician Francois Bernier, ‘when I reflect that there was not a single movement, nor even a voice heard, on behalf of the aged and injured Monarch.’

And yet Shah Jahan was not bereft during his years confined in Agra Fort. On the last day of the first month of 1666, it was a woman who bent over the frail Shah Jahan and whispered verses from the Quran. And it was to this same woman, his eldest daughter Jahanara Begum, that Shah Jahan confided his most pressing request – to provide for the other women weeping in the room: his ‘beloved consort’ Akbarabadi Mahal; the daughter from his first wife, the Shahzadi Parhez Bano, eldest of Shah Jahan’s surviving children; as well as ‘all the other ladies of the palace’. Thus, it was that an entire zenana of women, some of whom had voluntarily chosen this stifling existence out of devotion for him, provided solace and consolation to the wretched emperor during his last years.

But the sublime beauty of the Taj Mahal that Shah Jahan had built for his favourite wife, Arjumand Banu Begum (styled Mumtaz Mahal) attests to the fact that apart from Arjumand herself, every last one of the women in Shah Jahan’s life has been pushed into the shadows. And yet Shah Jahan was a man made and unmade by women, perhaps more than any of the other Great Mughals of India. In this essay, I will seek to recover the women who haunt the mausoleum of the Taj Mahal and inhabit the crumbling ruins of Agra, and attempt to understand the tenacious mechanisms that operate to ‘disappear’ these women.

That Timurid girl

In the winter of 1652, Aurangzeb passed through Agra on his way south from Kabul to take up his official duties in the Deccan, having failed to capture Kandahar. He described a visit to his beloved elder sister Jahanara Begum, writing that ‘he went directly to the garden of Jahanara, with the intention of calling on that princess of the people of the world.’

In this garden – the Bagh-i Jahanara – the two siblings spent a happy day together before Aurangzeb went on to visit the Taj Mahal, where he was dismayed to find the Mehtab Bagh flooded and the mausoleum itself water damaged after the heavy monsoon rains.

When Babur first founded his court in India after decades attempting to regain his lost homelands in Transoxiana, he set about consciously establishing himself as the last legitimate Timurid prince. For the Mughals were inordinately proud of their Timurid ancestry, tracing their lineage back to the fourteenth-century Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur.

Ebba Koch has demonstrated that it was Babur who introduced into the Indo-Gangetic plains the Timurid form of the char bagh. Jahanara Begum had inherited the Bagh-i Jahanara upon the death of her mother Arjumand, and it is the only architectural foundation that has been linked to that empress’s patronage. Jahanara Begum then transformed it into a magnificent palace garden with enclosing walls, gates, walkways, an octagonal tank and splendid waterfront towers.

In 1648, Shah Jahan cleared the space in front of Agra Fort that had been occupied by a ramshackle garden, intending to build a new market with a congregational mosque in the centre. At this point, Jahanara stepped in and addressed her father, and ‘begged that the sacred place of worship might be erected out of her personal funds.’ Shah Jahan approved her request, and Jahanara thus became the first woman in Mughal history to commission a congregational mosque.

Jahanara made sure that her name was personally linked to this commission in Agra by having a detailed description added to the mosque. On the frame around the mosque’s opening, Jahanara was further described as the personification of the sun, an image that was usually associated only with emperors: ‘This Holy house of God is built for the believers… its sight is pleasing to the eye and bestows divine light to those who believe… it is built by the order of Jahan Ara Begum… Luminous like the Sun…’ And if the sun is indeed an imperial symbol, then it is also a Timurid one. Lisa Balabanlilar has pointed out that one of the many ancestral Timurid traditions the Mughals venerated was the unique access to power and patronage offered to elite women – even young, unmarried and childless women.

And if ‘lighting the Timurid lamp’ was a veritable obsession with Babur, then over a hundred years later, an unmarried, childless Timurid woman was claiming the same exalted legacy for herself. Ursula Weekes has noted, by building the exquisite Taj Mahal, Shah Jahan hoped to surpass Timur’s mausoleum, the monumental Gur-e Amir at Samarkand. And if Shah Jahan was overtly announcing his Timurid magnificence, then through her architectural commissions in the imperial city of Agra and the lucid elaboration of her ambitions through her biography, Jahanara clearly set out to ‘light the lamp of the Timurids’, just as Shah Jahan himself was doing.

But time has not been kind to Jahanara’s legacy. The pavilions and walkways of the Bagh-i Jahanara have slowly disappeared through the turmoil of the centuries. The name of the garden itself has been corrupted almost beyond recognition to Zahara, Zahra or Zohra Bagh. Tragically, in October 2024, the top two floors and the dome of the remaining tower in the Bagh-i Jahanara collapsed entirely, with now practically nothing left of Jahanara’s once-elegant riverfront garden and her incandescent stated ambition to ‘light the Timurid lamp’.

Despite her searing ambitions, Jahanara was very careful to couch her aspirations in humility and dignity, referring to herself in her biography as that ‘wretched lowly person’. Perhaps Jahanara had learned her lesson from the fate of the Mughal woman whose immoderate aspirations had caused her to clash with Shah Jahan himself. And whose memory Shah Jahan would obliterate with singular focus – Nur Jahan.

The light of the world

In 1617, the resplendent young Shah Sultan Khurram returned victorious to his father Jahangir’s court at Agra, having successfully quelled the Deccan. The delighted Jahangir bestowed the title ‘Shah Jahan’ on his beloved son, but it would be his newest and last wife, the Persian Mehr-un-Nisa Begum, titled Nur Jahan (Light of the World), who would organise the most glittering celebrations.

Some of these celebrations may have occurred in Nur Jahan’s own garden, for she owned one of the earliest Mughal riverfront gardens in Agra. The Bagh-i Nur Afshan (the ‘Light-spreading Garden’, a play on Nur Jahan’s title) is the second and earliest of the extant Mughal gardens in Agra and was laid out soon after her marriage to Jahangir in 1611.

Both Bagh-i Jahanara and the Bagh-i Nur Afshan are early examples of what became the quintessential Mughal riverfront garden in Agra, in which the main building was placed along the riverfront, rather than in the middle of the garden. This garden would be used extensively by Nur Jahan to enact her visible imperial role.

Further along the eastern bank of the river, just outside Agra on the Patna-Agra trade route, Nur Jahan would build a monumental caravanserai. The serai was described by the traveller Peter Mundy as ‘a very fair one’, built entirely of stone, with arched and domed chambers, and with space for stabling 500 horses and sleeping 3,000 people. From this serai, Nur Jahan’s officers collected duties on goods transported along the river, giving her control over tariffs levied on goods coming from eastern India into Agra.

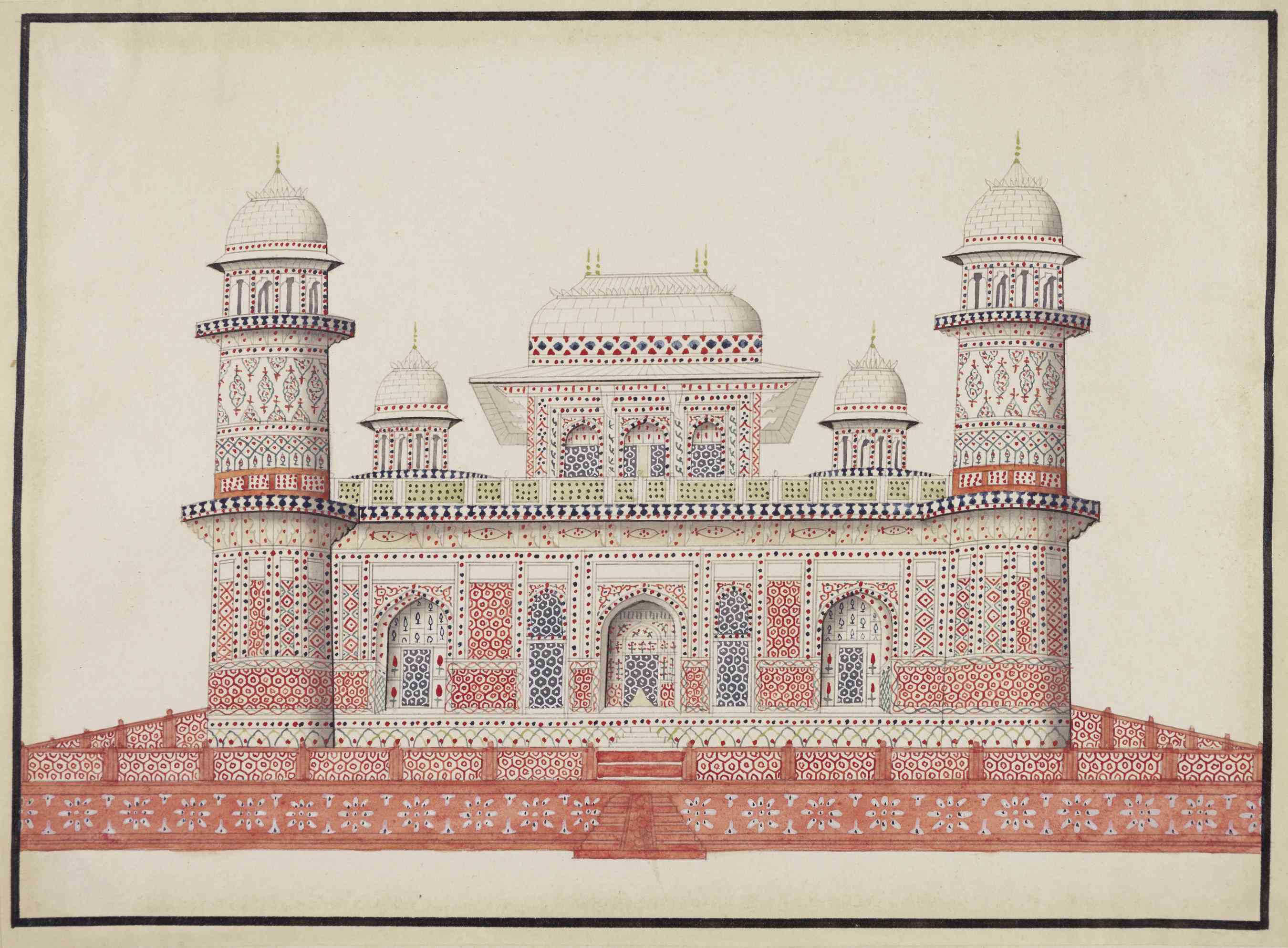

In 1622, when Nur Jahan’s parents Asmat Begum and Ghiyas Beg Tehrani died within three months of each other, Jahangir awarded the estate of the extravagantly wealthy Ghiyas Beg to his daughter Nur Jahan, completely bypassing her brother, Asaf Khan. Nur Jahan immediately began building a tomb for her parents within the riverside garden that had been owned by her father, who was bestowed the title Itimad-ud-Daula (‘Pillar of the Empire’).

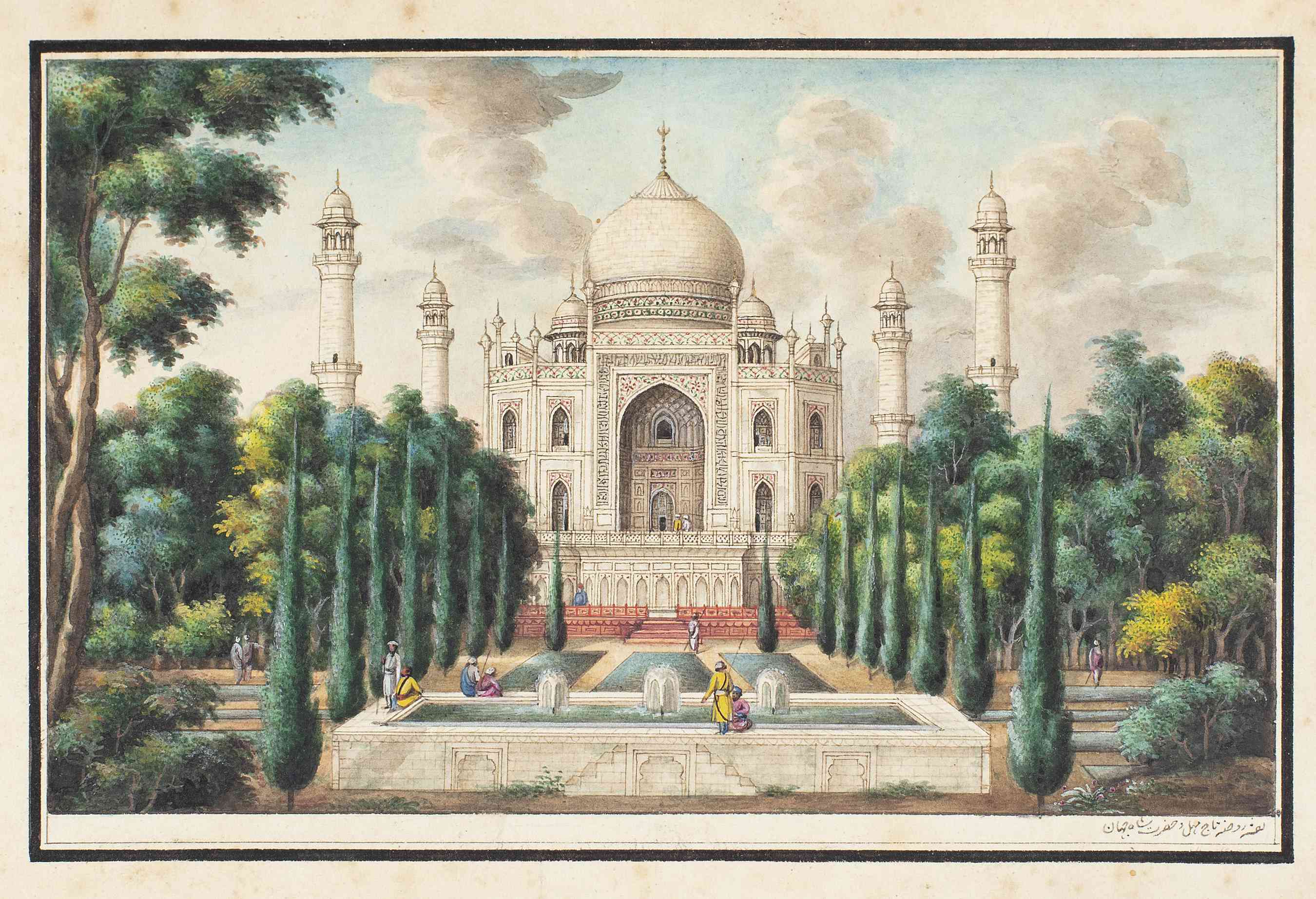

This garden tomb, which predated the Taj Mahal by a decade, would be the first of the great Mughal family tombs to be built in Agra. Strongly influenced by Nur Jahan’s own exquisite aesthetics, the tomb is a jewel of grace and refinement. It is made entirely of white marble rather than the red sandstone that had been preferred till then. The other striking innovation of the tomb is the extensive use of pietra dura inlay work that covers almost the entire surface of the building. The tomb also features Persian painted motifs such as ‘rose-water vases, wine cups, lilies, and red poppies,’ elements that ‘would appear later in the Taj’.

After his accession, Shah Jahan would not tolerate the presence of the woman who had opposed him. He would most certainly have blamed Nur Jahan for his fall from grace in his father’s eyes, becoming bidawlat (disgraceful) in Jahangir’s recording in lieu of the earlier fond iqbalmand (favoured by fortune). Scholars believe Shah Jahan would eventually ban the use of Nur Jahan’s gold coins, under pain of death, and have all her coins melted.

The Bagh-i Nur Afshan would become corrupted to Aram Bagh, and then Ram Bagh, thereby obscuring its relation to the ‘Light of the World’. There is intriguing evidence that Shah Jahan may have led to the effacement of Nur Jahan in other ways; there are suspiciously few likenesses painted of her still extant, and the magnificent books in her library appear to have been confiscated by the new emperor Shah Jahan – some books bearing the seal of Shah Jahan still show evidence of having first belonged to Nur Jahan. ‘It would seem,’ writes Michael Calabria, ‘that (Nur Jahan) was relieved of certain items in her possession at the time (Shah Jahan) seized power, perhaps by her own brother Asaf Khan!’

Beloved Consorts

It is impossible to conjure what Shah Jahan thought in the last year of his life as he looked upon the Taj Mahal from his Agra prison. By then the wife who was buried within such pristine loveliness had been dead for thirty-five years, and Shah Jahan had found comfort and consolation with other wives. Indeed, though the memory of Mumtaz Mahal is linked so tenaciously to that of Shah Jahan, she was not the first woman Shah Jahan married.

In 1610, when Shah Jahan was just nineteen years old, his first wedding was celebrated in opulent style, the festivities organised in Agra in the palace of Mariam-uz-Zamani, Jahangir’s mother. The bride was the daughter of Sultan Husain Mirza Safavi, the ruler of Kandahar, and was probably the woman who would later become known simply as Kandahari Begum. Kandahari Begum gave birth to a daughter variously called Parhez Banu, or Purhunur Begum. And then, five years after he married Mumtaz Mahal in 1612, Shah Jahan married the daughter of Shahnawaz Khan, the son of Abdur Rahim Khankhanan.

The biographers of Shah Jahan were all at pains to note that this third marriage was simply for political reasons, – to ‘assuage the feelings of the Khankhanan’, according to Qazwini. This woman had a son, Sultan Jahan Afroz Mirza, who died when still a child at Burhanpur. About these two women, who married Shah Jahan in the shadow of his great love, Mumtaz Mahal, we know less than nothing.

Much later in his life and long after Mumtaz Mahal had died, Shah Jahan’s biographers would become a fraction less intransigent, and we know that at least two of his later wives were particularly favoured. When Shah Jahan inaugurated his new capital city in Delhi at Shahjahanabad in 1648, the most important woman builder in the city, along with Jahanara herself, was a wife of Shah Jahan known only as Akbarabadi Begum.

In addition to the four important structures Stephen Blake noted had been built by Akbarabadi Begum in Delhi in 1650, this cherished wife had also been given a garden called Azzizabad by Shah Jahan in 1648. Inayat Khan even agreed that Shah Jahan had ‘showed kindness towards the other Ladies concealed behind the veil of chastity’ during the Nauroz (Persian New Year) celebrations of 1650, implying that there were a number of such beloved wives present. Of these women, two were particularly singled out, since they were ‘distinguished with superior regard’ – Akbarabadi Begum and Fatehpuri Begum.

Another wife, Sirhindi Begum, is also known to have commissioned buildings in Shahjahanabad in this late period of Shah Jahan’s life. Intriguingly, this wife was said to have built a garden near what is the Sabzi Mandi of Old Delhi today, and to have been buried within these gardens. These gardens were ruinous by the nineteenth century, and no tomb remains extant, but this might explain some of the confusing nomenclature around the ‘Subsidiary Tombs’ of the Taj Mahal.

Companionably but anonymously described as the ‘Saheli Burj’ (Tomb of the Female Friend), there are, in fact, four separate tomb enclosures within or near the Taj Mahal complex that bear this description. Two of these enclosures are within the Taj Mahal complex itself and flank the Jilaukhana to the south of the complex. They are missing from the official description of 1643, according to Koch, simply ‘because they were the tombs of women.’

With their marble-clad domes and elegant pillared verandahs, are more likely to be those of the ‘beloved consorts’ of Shah Jahan’s later years – Akbarabadi Mahal and Fatehpuri Mahal. Koch has further noted of the eastern tomb that ‘the flowering plant at the foot and the solar motif at the head are smaller, simplified versions of the designs on Shah Jahan’s cenotaph’ itself, denoting the special closeness the emperor had for Akbarabadi Mahal, whose well- being he particularly entrusted to Jahanara Begum as he lay dying.

Outside the Taj Mahal complex to the east of the enclosure is a tomb garden and mosque which bear a great deal of resemblance to the two Saheli Burjs inside the forecourt. Shrouded in mystery, these structures have not been mentioned in any of the official court histories or in later plans of the Taj, and the identity of the person buried in the tomb is unknown, though it is believed to be a woman. It is currently assigned to ‘Sandali Begum’, while the adjoining mosque is called the ‘Sandali Masjid’ (Sandalwood Mosque) or ‘Kali Masjid’ (Black Mosque).

Another ASI plaque attributes this tomb to Kandahari Begum, Shah Jahan’s very first wife. However, according to Latif, Kandahari Begum had a large garden in the city of Agra in which she was later buried. This garden eventually became ‘the town residence of the Maharaja of Bharatpur’ and the tomb is no longer extant. Might this tomb be that of Shah Jahan’s third official wife, the daughter of Shahnawaz Khan, whose tomb has never been identified? Or might it be that of Shah Jahan’s oldest surviving daughter, Parhez Banu, whose fate the emperor was so worried about in his dying hours?

When Abu’l Fazl began work on the Ain-I Akbari for emperor Akbar in the 1590s, he would, for the first time in the history of the Mughal empire, declare that the Mughal women were pardeh-giyan (the veiled ones). The women would be further hidden behind grandiose titles, which made them indistinguishable, Hindu, Persian or Turk.

So ferocious would be this vigilance over royal women’s identities that entire lifetimes would become effaced behind the most nameless and bland of recordings. Shah Jahan’s biographers, too, would stoutly refuse to betray even a glimmer of these many women’s identities, while Mumtaz Mahal would be eulogised beyond any recognisable humanity. Interestingly, a vibrant celebration of a feminine presence carries on even today at one of these Saheli Burjs – the Sandali Begum’s tomb.

According to Sarthak Malhotra: Though the identity of the person entombed at the Tomb of (Sandali) Begum has been lost to time, women from neighbourhoods across Agra visit this tomb every Thursday to sing songs, light incense sticks, and offer food and milk to cats as richly nuanced acts of Sufi devotion. The tomb, for them, commemorates the sacred memory of a saint whom they identify as Sandali Begum and… even though the historical records remain silent about the women of the Mughal past, their presence flourishes today.

Beyond the Graves

For the millions of visitors who walk through the Taj Mahal every year, the only woman they will remember is Mumtaz Mahal. As Gavin Hambly has noted, ‘generations of scholars of the Islamic past, whether they emerged from an indigenous Muslim tradition or were part of the European Orientalist tradition, largely ignored the existence of women.’

In addition to the insouciance of this disregard is the deliberate elision by the emperors’ biographers and the additional destruction of fragile structures due to a volatile history. Recent scholarship around Mughal women’s matronage and presence has sought to question this absence. For the women of the Mughals of India were never invisible, they were simply rendered so.

This is a shorter version of Ira Mukhoty’s full essay titled, “A Cartography of the Feminine Presences Around the Taj” from the book The Mute Eloquence of the Taj Mahal, accompanying the eponymous exhibition on view at DAG, New Delhi, until December 6.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting