By Dilip Bobb

Films are stories told on celluloid and screened in cinema halls. Increasingly, they are being staged in courtrooms, or their release decided in courts, as individuals or sections of citizens object to the contents and depiction of certain characters or scenes, even distortion of historical facts.

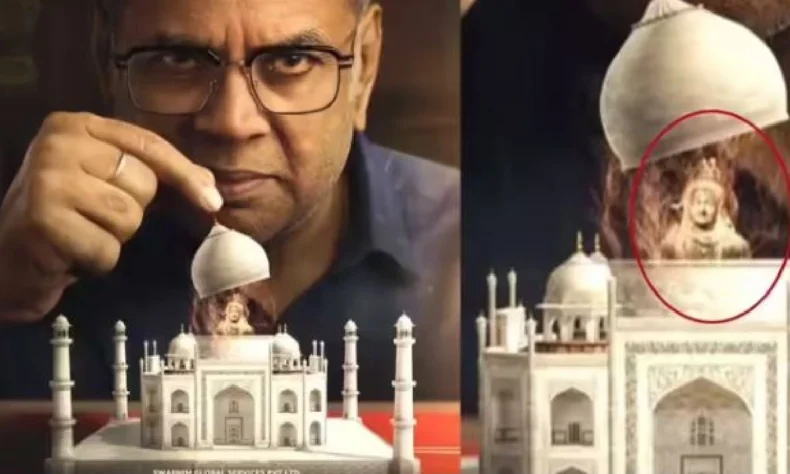

The latest to join the ranks of such films is The Taj Story. The film delves into controversial questions surrounding the construction of the Taj Mahal, challenging conventional historical narratives about one of the world’s most iconic monuments. Two public interest litigations (PILs) were filed seeking a ban on the film and a review of its certification.

The petitions alleged that the film distorted historical facts about the Taj Mahal. Many critics have called it a “propaganda” film which appears to support the right-wing theory that it was built on the site of an ancient Hindu temple, originally a Shiva temple called: “Tejo Mahalaya”. This theory alleges that Mughal emperor Shah Jahan appropriated the existing structure to build the mausoleum for his wife Mumtaz Mahal, despite the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) stating there is no evidence to support the temple theory.

Ahead of its release, the Delhi High Court had refused to grant an urgent hearing to the PILs filed against the release of The Taj Story. The PIL alleges that the movie is based on “fabricated facts” and promotes a “particular propaganda” intended to gain political mileage and incite communal disharmony.

According to the plea, the film’s trailer, launched on October 16, 2025, shows the dome of the Taj Mahal with a saffron flag above it and reflections showing a figure of Lord Shiva, implying that the monument was originally a temple. The petitioners claim that such imagery “distorts historical facts, misrepresents India’s composite culture, and risks provoking communal unrest”.

Film critic Devesh Sharma of Filmfare wrote in his review: “The film pretends neutrality while continuously feeding an ideological hunger.” The film’s narrative draws inspiration from claims popularized by writer Purushottam Nagesh Oak, widely debunked by mainstream historians and archaeologists, including the ASI.

The Supreme Court had earlier dismissed Oak’s petition to declare the Taj Mahal a Hindu temple, describing his views as a “bee in his bonnet”. Veteran character-actor Paresh Rawal, who plays the lead role in the film, had come under fire for his initial social media posts about the Shiva connection, which he deleted later, saying that the audience can make up their own mind.

The late PN Oak was a pseudo-historical Hindutva author and among his prominent claims were that Christianity and Islam are both derivatives of Hinduism; that Vatican City, Kaaba, Westminster Abbey and the Taj Mahal were once Hindu temples dedicated to Shiva; and that the Papacy was originally a Vedic Priesthood. While all of these claims are demonstrably false and incompatible with historical and archaeological records, their reception in Indian popular culture has been accepted by some right-wing sections of society. Oak wrote numerous books in a bid to alter mainstream history narratives, some of which have led to court cases. The Taj Story is an adaptation of his preposterous, right-wing views.

The Taj Story’s legal objections are reflective of another “story”, The Kerala Story, which also had a strong communal angle. The 2023 film’s plot follows a group of women from Kerala who are coerced into converting to Islam and joining the Islamic State. Marketed as a true story, the film is premised on the Hindutva conspiracy theory of “love jihad”. After legal interventions, the filmmakers were made to accept the addition of two disclaimers: that the film was a “fictionalised” depiction of events. The film was heavily promoted by the BJP, which leveraged the film in its campaigning for the Karnataka assembly election. The film received heavy criticism for its illogical screenplay and “Islamophobic propaganda”. It faced protracted litigation and protests, primarily in Kerala, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu.

Another film which also attracted legal objections for allegedly promoting Islamophobia was The Kashmir Files (2022) based on the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits.

It was also heavily criticised for historical distortions. Despite facing certification issues and PILs, the lower courts refused to halt its release.

Other films that have faced legal obstacles are:

- Haq (2025): Inspired by the landmark 1985 Shah Bano maintenance case, it faces a legal notice and court action from Shah Bano’s daughter, Siddiqua Begum. Her family alleged that the filmmakers used the life story of Siddiqua’s mother without consent, breached their privacy, and presented a potentially distorted version of events. The film is scheduled for release later this month.

- The Bengal Files was released on September 5, 2025. The film had received an A (adults only) certificate from the CBFC citing extreme violence and gory content. Writer/director Vivek Agnihotri, who also wrote The Kashmir Files, had warned that he will pursue legal action if West Bengal prevents the release of his film. Prior to the film’s release, Agnihotri publicly appealed to West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, urging her not to impose a ban on the film. The issue escalated further when Amit Malviya, the chief of BJP IT Cell, accused the Mamata Banerjee-led Trinamool Congress government of unofficially banning the film, while the accused party denied any involvement in the film’s non-release, asserting that the decision rested solely with theatre owners and multiplex operators. Theatre owners in Kolkata clarified that no slots were available for the film. On September 23, 2025, the Calcutta High Court questioned the West Bengal government whether it had imposed any restrictions on the film’s release in the state. The state government told the Court that there was no such official or unofficial ban on the film, which depicts communal violence prior to Partition.

- The Delhi High Court had refused to entertain a PIL that sought to change the title of the movie Prithviraj. The movie stars Akshay Kumar. The PIL was filed by the Rashtriya Pravasi Parishad, arguing that using the name “Prithviraj” without a dignified prefix like “Samrat” (emperor) disrespected the great Indian king. The film’s makers subsequently changed the title from Prithviraj to Samrat Prithviraj a week before its release. The Gurjar community also filed a plea alleging that the film wrongly portrayed Prithviraj Chauhan as a Rajput king, claiming he was a Gurjar ruler. The Delhi High Court disposed of the plea after the filmmakers (Yash Raj Films) stated in court that the film was “caste-neutral” and intended to portray him simply as a great Indian warrior and king, without mentioning him belonging to either community.

- The Salman Khan and Katrina Kaif starrer Bharat faced legal objections after a petition was filed in the Delhi High Court against the film for “hurting patriotic sentiments”. The petitioner claimed that “Bharat” cannot be used for any professional and commercial purposes and sought a change of the title.

- The Gujarat High Court (2017) dismissed a PIL seeking restraint on release of the Deepika Padukone-starrer Padmavati on the ground that the Rajput queen’s character has been portrayed in the film in a derogatory manner and historical facts distorted. A bench of then Chief Justice RS Reddy and Justice VM Pancholi refused to entertain the PIL. A group from the Rajput community have moved the courts saying Padukone was shown dancing in the movie which is against historical fact since she is worshipped in Rajasthan.

- A PIL has been filed in Uttarakhand High Court requesting a ban on the release of the film Kedarnath, alleging that the film “misrepresents facts and hurts Hindu sentiments”. Avatar Singh Rawat, the counsel for the petitioner, said that the film portrays “a Muslim boy falling in love with a Hindu girl, and when they fail to unite, both pray to bring upon destruction after which the 2013 floods take place”.

Other movies that have faced legal objections include a PIL seeking a ban on the film The Accidental Prime Minister, saying that it caused damage to the name and stature of the former prime minister Manmohan Singh. A bench of then Chief Justice Rajendra Menon and Justice V Kameswar Rao of the Delhi High Court rejected the PIL. The film is based on a similarly titled book by Sanjaya Baru, former media advisor of Singh. Actors Anupam Kher and Akshay Khanna play Manmohan Singh and Baru, respectively in the film.

Increasingly, filmmakers, scriptwriters and directors are turning to contemporary events to base their productions on. In an increasingly polarised country, that can only lead to legal actions and courts stepping in. Whether it is The Taj Story, The Kerala Story or The Bengal Files, filmmakers are stretching socio-political and communal boundaries. For some, it may be the lure of commercial success when addressing a dominant community, for others it may be a reflection of their own views, but it is leading to courts having to intervene and make a decision whether to usurp the workings of the censor board.

There are increasing allegations that a title or plot offends religious, historical, or social sentiments of a large group of people. There are also increasing claims that a film’s title or content based on that title manipulates historical facts for a particular narrative, potentially leading to public unrest (the PIL against The Taj Story). The most common legal objection is that the release of a film with a controversial title or subject matter could trigger communal tensions or disturb public peace.

High Courts often dismiss or refuse urgent hearings for PILs against such objections, especially if the film has already received Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). The judiciary has often emphasized that the CBFC, currently headed by lyricist Prasoon Joshi, is the appropriate body for certification and the court should not overstep its role.

So far, courts have entertained a PIL only if it genuinely involves a public interest matter. Courts generally uphold the spirit of creative freedom, ensuring that filmmakers are not unduly restrained unless there is a clear and present danger to public order.

Till now, courts across the country have chosen to balance public concerns with the principles of censorship law and freedom of creative expression. Those guardrails are, however, being increasingly tested. More so considering that they come under the Cinematograph Act of 1952, when love and conjugal bliss was in the cinematic air, not separate realities.

—The writer is former Senior Managing Editor, India Legal magazine

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting